- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Charlie Squadron – the iron fist of the South African Defense Force's 61 Mechanised Battalion Group – led the way on 3 October 1987 during the climactic battle on the Lomba River in Southern Angola. Not only were they up against a vastly superior force in terms of numbers and weaponry, but they also had to deal with a terrain so dense that both their movement and sight were severely impaired. Despite this, the squadron nearly wiped out the Angolan forces' 47 Brigade. In Ratels on the Lomba, the reader is taken to the heart of the action in a dramatic recreation based on interviews, diary entries and Facebook contributions by members of Charlie Squadron. It is an intensely human story of how individuals react in the face of death.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ratels on the Lomba by Leopold Scholtz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

DEATH AT THE DOOR

It is 3.00 am on 16 September 1987. A few kilometres south of the Lomba River in the southeast of Angola, in the temporary base of Charlie Squadron – the armoured fist of 61 Mechanised Battalion Group – the officers and NCOs wake their men. They’ve been at the front for more than two weeks now, but have so far seen no action. They have only heard the ominous thunder of artillery and seen the flashes in the distance.

Today they will look death squarely in the eye for the first time. A number of the men will have narrow escapes; others will be honoured for bravery under fire … and some will die. Their orders are to take on the Angolan 47 Brigade in its hide south of the Lomba River. This brigade is the only one of four in the area that has been able to penetrate south of the river. As such, it presents a danger that has to be neutralised.

If this doesn’t happen, the success of Operation Moduler may hang in the balance. Moduler is part of a South African Defence Force (SADF) campaign in support of the Angolan rebel movement Unita against a major offensive by Angolan government forces.1

That morning Second Lieutenant Len Robberts, the squadron’s second-in-command, decides not to have any breakfast. His biggest fear is being shot in the gut and so he would rather go into action on an empty stomach.

When I spoke to the men of Charlie Squadron many years later, most of them denied feeling nervous that day. However, they admitted that it was not because they were so brave but rather that they were too young, too stupid and too inexperienced to know any better. Many of them thought it would be a great adventure. They would soon receive a rude awakening.

The battle officially starts at 6.23 am when the South African Air Force (SAAF), as planned, bombs the positions where 47 Brigade is supposed to be. There is some confusion regarding this attack: some sources state that the four Buccaneer bombers, which had to follow up an initial strike by nine Mirage fighters, had to turn back as they were picked up by enemy radar, but several Charlie Squadron men are adamant that they were mistakenly bombed by those same Buccaneers.

Len Robberts remembers it well: ‘We were deployed and began moving early, and we all stood along a shona [a clearing in the bush with a flood plain] and moved along it in line abreast. All of a sudden – it was only 200–300 m from us, not far at all – our own air force bombed us, and it’s just flames where you look. Then they saw we were SADF and flew away. Luckily they missed, because we were standing nicely in a row, ready to advance.’

On the ground, the troops at first don’t realise that they are being blasted by their own aircraft. In his diary, Robberts writes, dramatically: ‘Bombs burst everywhere around us, or so it feels. They explode about 200–300 m from us. “All stations, go for cover – MiGs!” Hatches closed.’

Then the artillery weighs in, and the G-5s belch fire while the Valkiri rocket launchers rain death on the defenders. At 7.23, exactly an hour after the action starts, 47 Brigade headquarters radios to Cuito Cuanavale that all aircraft bombs were ‘on target’ and ‘Things are looking very bad’. By 10.49 the anguished message is ‘situation now very bad’.2

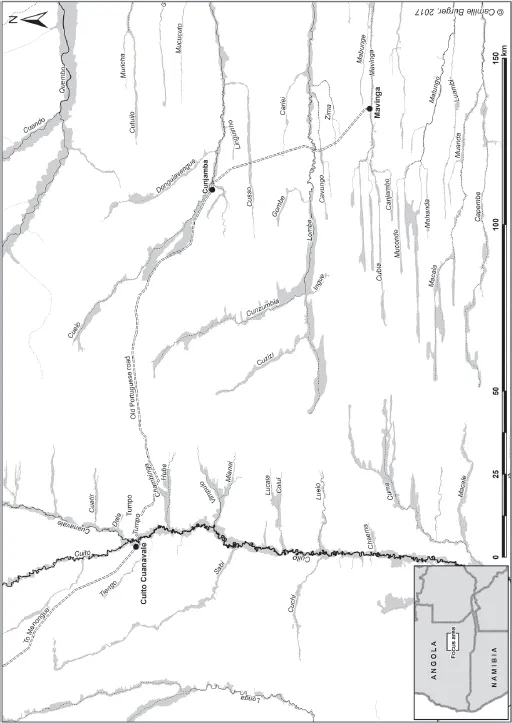

In accordance with the South African Army’s mobile warfare doctrine, Colonel Deon Ferreira (OC 20 SA Brigade) and Commandant Kobus (Bok) Smit (OC 61 Mech) had devised an attack plan which was, at any rate on paper, very intelligent. Smit would attack from an unexpected direction. He was ordered to advance from the east past 47 Brigade’s southern flank, and then swing around and attack the Angolans unexpectedly from the west (see map on p. 34).

Smit’s force – Combat Group A – would conduct the main attack, with Dawid Lotter’s Combat Group C in support. Combat Group A consisted of Alpha Company and Charlie Squadron of 61 Mech, with a company of 32 Battalion. Combat Group C consisted of Bravo Company and the anti-tank platoon of 61 Mech.

Smit merged Charlie Squadron and Alpha Company into combat teams by combining two Ratel-90s with two Ratel-20s. PJ Cloete was not happy about it, as his squadron was by now a well-oiled machine and used to operating as a whole. Now there would be no more cohesion, he felt. But he was a junior officer, and junior officers obey orders from the senior officers.

Smit’s Combat Group Alpha was put on the left flank, closest to the river, where the enemy’s resistance was expected to be at its strongest. Combat Group C would cover the right flank. If needed, Combat Group C could swing northwards to act as a direct fire support base.3

But, as the Prussian General Helmuth von Moltke (the Elder) once famously said, battle plans generally do not survive first contact with the enemy. On the battlefield, Murphy’s Law is king: if something can go wrong, it will. In this instance, very little went right and the most important reason for this was the dense bush in which the South Africans had to operate. As Captain Danie Crowther, an intelligence officer with 61 Mech, described it: ‘You can’t see more than 20 metres in that bush, which means that your main weapons, your anti-tank weapons, cannot be applied. But terrain is neutral, because it’s the same for the other forces as well. What Fapla did in that situation was these guys were very good at digging, and they dug themselves in. We didn’t like that very much. We preferred mobile warfare, and we would rather move to a point where we attack and be able to move out quickly and never get dug in to a specific situation except the situation where we had the river crossing.’4

The good start the South Africans have is only temporary. Combat Group Alpha struggle desperately eastwards through the bush and sandy soil in its march past the southern side of 47 Brigade’s positions, its advance painfully slow. The western part of the objective is only reached at 2.00 pm, hours late, when the troops are already getting tired.

When first contact is made, Bok Smit has his hands full to retain tactical control, as the line of sight is no more than 30–40 m, often as little as 10 m. This means the car commanders can barely see the cars to their left and right, and the cohesion of the attack becomes a real problem.

The infantry debus and move forward on foot. The normal drill for an attack like this is what the military call ‘fire and movement’. In other words, one troop or platoon advances in ‘jumps’ of, say, 40–50 m, while its fellow troop or platoon covers it with a deluge of fire to keep the enemy’s heads down, and then the movement is repeated. But that is almost impossible if you can see neither the well-hidden enemy nor the vehicles to your left or right. Furthermore, the element of surprise is lost.

The enemy apparently pulled back deeper into the almost impenetrable bush and fired, as a SADF report put it, ‘effectively with RPG and small arms’. The dense bush limited the armoured cars’ line of fire, which meant ‘the Ratel-90s could not be utilised to [their] full potential’.5

In fact, Combat Group Alpha was too far to the north. They did not clash with 47 Brigade’s main body, but with a flanking element, which gave the Angolans time to organise a reaction. And that consisted of a deluge of small-arms fire, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) and heavy artillery fire. ‘We were looking for the enemy but just couldn’t see them because they were so well dug in among the thick bush,’ Major Laurence Maree, logistics officer for 61 Mech, later told writer Fred Bridgland.6

Ratel driver Conrad Farrell remembers: ‘Suddenly we took on heavy-calibre machine-gun fire from a position at 10 o’clock. Under a tree on an elevated bank I could make out the silhouette of a BRDM or BTR [Soviet armoured personnel carrier]. They look very alike from the front, and this vehicle was quite far away. I directed James [Sharp, gunner] to their position with the 90 mm, which he did in a flash. Our first round hit the ground to the right of them within a few metres.

‘James only really saw them after his first shot was fired because they were behind the tree and far away, and took his first shot on my directions alone. They must have realised we were onto them, and as James reloaded, got them into his sight, adjusted and fired his second shot, I saw two bodies jump from the top hatches, still in mid-air as our round struck the vehicle and everything exploded.’

Sharp remembers it mostly the same way, even if his retelling is more colourful: ‘My commander, Lieutenant Martin Bremer, sees a BRDM 300–500 m away, and tries to get me on target. He gives all the correct orders, but I don’t see the blessit thing! Then Conrad Farrell also sees the BRDM, and I start to stress. Lieutenant Bremer keeps his cool and says according to his line sight I am basically on target and he orders: “Shoot!”

‘I hesitate, as I don’t want to give our position away in case there were tanks also. He says again: “Shoot, shoot, just fucking shoot, Sharp!” I comply.

‘The first round impacts the tree behind which the BRDM stands and splits it in two through its fork. There he stands, as big as life, and some of the crew who stood outside look surprised at the tree. I think one also stood in the turret. The second round was a bull’s-eye and the vehicle burst in flames.’

Several of Charlie Squadron’s men had narrow escapes that day. Corporal Donald Brown’s car (31C) got stuck on a tree stump and could not move forward or backward. Being unable to move in a battle like this is tantamount to inviting death. So Corporal Francois Fouché (in 32B) pushed him off with his own Ratel.

Suddenly, Fouché saw Brown throwing his hands in the air and falling down into the Ratel. Cold sweat dripped off him; had he just witnessed a buddy’s death? Luckily, several moments later Brown’s head emerged in the turret hatch, but with a rag around his throat. Later, he showed Fouché how an enemy bullet had scraped just below his jaw. If he had hunched even just a few centimetres lower, his head would have exploded in a hundred pieces.

Second Lieutenant Martin Bremer, commanding a troop of four armoured cars in Charlie Squadron, also had a narrow escape. One of his crew commanders froze and refused to stick his head out of the turret. The car (31A) then pulled back onto a tree stump and got stuck. With the enemy throwing everything at the attackers, Bremer jumped out, bullets flying around him, ran over to the stricken Ratel and connected the towbar to pull it out.

According to Bremer, he jumped out of his Ratel without thinking properly: ‘I definitely woke up when my feet hit the earth. The noise was intense and one could continually hear a “ping-ping” against the sides of the Ratel. Actually, there was no way to change my decision; I would undoubtedly have been shot had I tried to climb the Ratel’s sides again. It felt as if the entire 47 Brigade was watching me and trying to kill me.

‘I then grabbed the towbar and ran over to the stranded 31A. A Ratel towbar is heavy, but I can’t recall that I felt the weight. I could also hear a few pings on the towbar as the shooting continued. My crew on 31, James Sharp and Conrad Farrell, in the meantime learnt what was going on, turned our vehicle around and moved it back end first towards Alpha [Company] …

‘The next moment I notice James on top of the Ratel. He was under fire as he threw the shackle towards me with a grin, as if to say, “You stupid piece of shit …” He remained cool under pressure and realised I didn’t have the necessary tools. Lieutenant ‘Padda’ Harmse [of Alpha Company] also came to help fix the rod, and so we managed to pull out the vehicle.’

Bremer’s action speaks of exceptional bravery. PJ Cloete, his commander, recommended him for an Honoris Crux decoration, which was awarded a few months later. In one of my interviews with him, the ever-modest Bremer emphasised that Farrell, Sharp and Harmse must also get credit for what they did.

For the men of Charlie Squadron, the events of 16 September 1987 signalled the start of Operation Moduler. But this was just the beginning. Intense suffering and trauma still lay ahead for them and 61 Mech. They just did not know that yet.

The operational area

Chapter 2

HOW OPERATION MODULER CAME ABOUT

What gave rise to the events of 16 September 1987? Why did death knock on the door of Charlie Squadron that day? When their 12 Ratel-90s crossed the border between South West Africa and Angola two weeks before, the Border War, which had been waged intermittently since 1966, was escalated even further.

The territory known today as Namibia was annexed by Germany in 1884. During the First World War, German South West Africa was occupied by the Union of South Africa in 1915 on behalf of Britain. With the defeat of Germany, the territory, then known as South West Africa (SWA), became a League of Nations mandate, administered by South Africa. When the League was replaced by the United Nations (UN) in 1945, South Africa continued its occupation ‘in the spirit’ of the League’s mandate. South West Africa, also known as ‘Suidwes’ or ‘South West’, was ruled essentially as South Africa’s fifth province.

However, in 1959, the South West Africa People’s Organisation (Swapo) was founded to end the South African occupation. The League of Nations mandate was officially revoked by the UN in 1971, when the name ‘Namibia’ came into use. By that time, Swapo and its armed wing, the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (Plan), had started an armed insurrection to drive the South Africans out. Swapo also protested against the National Party government’s policy of apartheid.

The first armed clash in what became known as the Border War took place on 26 August 1966, when a combined force of South African paratroopers and policemen swooped on the only military base Plan ever had, at Ongulumbashe, in Ovamboland, in the far north of the country. The Swapo combatants scattered, and in the ensuing years waged a low-intensity guerrilla war. However, since their near...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Poem

- Contents

- Foreword by Roland de Vries

- Introduction

- List of abbreviations

- Timeline

- 1. Death at the door

- 2. How Operation Moduler came about

- 3. The tools of war

- 4. The storm clouds gather

- 5. Baptism of fire

- 6. The road to Armageddon

- 7. To hell and back

- 8. Tragedy strikes

- 9. Aftermath

- 10. Death from the sky

- 11. Punch-drunk forward

- 12. The final phase

- 13. Going home

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- List of sources

- Notes