![]()

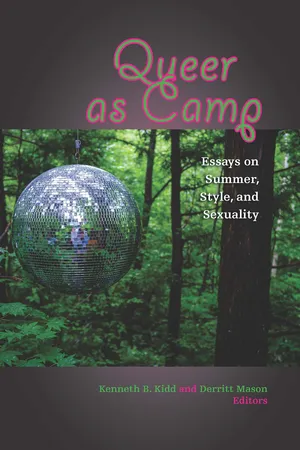

PART I

Camp Sites

![]()

“The most curious” of all “queer societies”?

Sexuality and Gender in British Woodcraft Camps, 1916–2016

Annebella Pollen

In the years during and after the Great War, disaffected with the apparent militarism and imperialism of Boy Scouts, British pacifists established rival outdoor youth organizations. These new organizations returned to some of the founding ideas of Scouting in the form of the “woodcraft” system of outdoor education pioneered at the turn of the twentieth century by Ernest Thompson Seton and latterly absorbed into Baden-Powell’s organization. To these ideas each of the new organizations—the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry, the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, and Woodcraft Folk—added their own distinctive philosophies, drawing on psychology, spirituality, art, and politics, to provide idiosyncratic camping experiences across genders and ages. Camp in this context was more than leisure, and more than an escape from encroaching industrialization—it was a personally and socially transformative space, rich with utopian possibility.

The British woodcraft movement’s subversions represent a distinctive and elaborate queering of the Boy Scout ideal. Through their futurist visions and revivalist performances, members acted out their radical ideals for a hybrid new/old world. Alongside these activities, each group developed detailed and sometimes unorthodox ideas about “sex instruction” and “sex equality” interlinked with complex theories of camping. As such, new ideas about social relationships ran through woodcraft organizations’ vision and were played out under canvas. In the temporary worlds of primitivist camps in the heady period of change after the Great War, alternatives to so-called civilized life could be tried on for size. Gender and sexuality became prime sites where the limits of experimental practices were tested and contested, and aspects of these challenges continue in the organizations’ twenty-first-century manifestations.

Through an investigation of woodcraft theories and practices, this essay examines the movement as a case study of oppositional ideals in the interwar period, when camping and experiments in living intertwined. While woodcraft organizations in Britain have always been much smaller in scale than numbers of Scouts and Guides, and their founding ideas were far from mainstream, their position as aspiring cultural revolutionaries meant that they inhabited a space—literally and figuratively—as outsiders. This essay presents views from the three most prominent woodcraft organizations, each founded during or shortly after the Great War. The Order of Woodcraft Chivalry was the first pacifist coeducational breakaway from Scouts. Founded in 1916, it was at its most productive in the 1920s and 1930s with public projects including the progressive Forest School for children and Grith Fyrd craft training camp for unemployed men. The organization recently celebrated its centenary; it is now a very small cluster of descendants of early members. The flamboyant, artistic Kindred of the Kibbo Kift was established as an all-ages, mixed-gender alternative to Scouts in 1920 but only lasted just over a decade as a woodcraft organization before being radically remodeled into an economic campaign group (The Green Shirts) and latterly a short-lived political party (The Social Credit Party of Great Britain and Ireland). Finally, Woodcraft Folk was founded in 1925 following a schism in Kibbo Kift over political direction; it continues to thrive as an outdoor-focused and democratic organization with around 15,000 adult and child members in groups spread across the United Kingdom.

Camping as an Oppositional Practice

Camping may seem to be an innocuous leisure activity, merely providing a low-budget holiday; as such, it could be of little social or political consequence. Yet camping has also been described as essentially socialist in character. In G. A. Cohen’s analysis, as a system based on collective property and mutual giving, camping demonstrates in miniature “that society-wide socialism is equally feasible and equally desirable” (11). Camps are clearly diverse in their organization and ideologies, but they have nevertheless been characterized as extraordinary and exceptional places; as philosopher Giorgio Agamben has put it, the camp is “a piece of land placed outside the normal juridical order” (1). For their capacity to stand outside conventional social structures, camps have become utilized for protest and as sites where the building blocks of society can be symbolically deconstructed and remade. Angela Feigenbaum, Fabian Frenzel, and Patrick McCurdy, for example, have argued that the collective nature of camps has been particularly effective in forging “communities of understanding.” In their conception, camp is a “unique structural, spatial and temporal form that shapes those who live, work, play and create within it” (8). A further essential aspect of camp—its transitory nature—necessarily results in a shift in everyday practices. To use the anarchist Hakim Bey’s terminology, camps encapsulate a “temporary autonomous zone” where intentional communities can form “pirate utopias.” The temporary nature of camping allows for the suspension of norms and the trying on of new worlds for size. As camping historian Matthew de Abaitua writes, “Camping promises nothing permanent. It is a way of trafficking between what was and what could yet be” (60).

The romantic promise of camping has long held an allure for reformers at odds with the modern world. Since the writings of Henry David Thoreau in the mid-nineteenth century, a substantial body of literature has been produced in Britain and America espousing the ostensibly moral value of withdrawing from urban life with only the most basic means of survival on hand. Full of motifs of savages, Indians, gypsies and the like, such discourse contains much that can be critiqued as privileged colonial fantasy, but the experience of going back to the land clearly had (and has) anti-establishment potential. The “pastoral impulse,” as Jan Marsh has described it, was particularly prevalent from the 1880s in Britain among socialist campaigners, who saw the countryside disappearing from view and reconfigured it as an idea. “Country” became an oppositional and idealized space in positive relationship to the rapidly expanding, polluted, and industrialized city (Williams). For those late-Victorian reformers who campaigned for all-round social improvement, new enthusiasms for cycling, hiking, and camping were part of a broader urge for the simplification of life. Campaigns for fresh air and radiant health were a core part of these left-wing desires, which aimed to reform all aspects of life, from new ways of eating and dressing to new forms of social relationships.

Key proponents of these lifestyles, which espoused anti-industrial and alternative causes from vegetarianism and self-sufficiency in food production to the revival of handicrafts, included John Ruskin, William Morris, and Edward Carpenter. Carpenter, in particular, offers a bridge between the late nineteenth-century practices and their manifestation among alternative youth organizations in the 1920s. Carpenter’s writings were wide and included transcendental poetry, tracts denouncing industrial civilization as a social ill, and those promoting a wide variety of loving relationships, including same-sex, unconstrained by convention (Rowbotham). For his pioneering ideas and lifestyle—he maintained an openly gay relationship with his working-class lover, George Merrill, at their smallholding in the north of England—Carpenter became something of a guru among the socialists and feminists who were challenging convention across a range of causes, in particular in relation to the emerging discipline of sexology.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, Carpenter and his friend and colleague, the physician Havelock Ellis, became figureheads for the emergent “sexual science” informed by new psychological studies, which aimed to take seriously a wide range of sexual experiences and to develop a new vocabulary for their understanding. In the context of highly charged anxieties about “degeneration” and “deviance,” prostitution and venereal disease, the radical position of sex reformers on abortion, divorce, and same-sex relationships remained far from mainstream. As Alison Oram notes, interest in sexology in the years up to the Great War was not respectable and was largely confined to intellectual elites and “radical fringe groups” (219). In this context, it is clear to see that woodcraft organizations, especially in relation to their role with children, were unusual in having frank “sex-instruction” built into their educational programs.

The extent to which these practices can be described as a form of queering depends on one’s understanding of the term. As an expansive definition, David Halperin has argued that queer is “whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant” (62). As I will argue, while British woodcraft organizations may not have been exclusively concerned with sexual behavior, let alone what might be understood as queer sexual behavior, their activities nonetheless challenged conventional approaches to sexuality as part of their broader challenge to social norms. In thinking of woodcraft organizations as queer, I draw on Matt Houlbrook’s argument that “thinking queer” is a historical methodology. As such, it moves away from simply seeking to restore an LGBT history; instead, it performs the work of critical history in disturbing categories. Houlbrook applies this method to interwar Britain, a period that he characterizes as one of “massive social, economic, cultural and political upheaval” (135), when emergent attempts to characterize and pathologize sexual orientations, roles, and practices were particularly insecure. The examples that Houlbrook examines are, like woodcraft organizations, studies of transgressive behavior that resist cultural convention. He persuasively argues, “thinking queer is too useful to be confined to the study of the queer” (136).

Sex and Gender in Woodcraft Organizations in the Interwar Period

I. O. Evans, a former Scout and subsequently an enthusiastic member of several woodcraft organizations, compiled a book of the philosophies and practices of the British woodcraft movement in 1930, which included a chapter outlining woodcraft approaches to sex. Evans summarized that, until recent years, youths had only “ignorant filthy gossip” for guidance, leaving them “to blunder experimentally amidst the most frightful perils.” He added, happily, that this period was on its way out, and noted, significantly, that “its passing synchronizes with the rise of Woodcraft” (177). To Evans, woodcraft organizations were at the fore of open-mindedness. Sex education in organizations such as the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry and Kibbo Kift was “very thorough-going.” By contrast, he noted Baden-Powell’s alarmist attitude to “self-abuse” and how Scouts’ “reactionary” attitudes to gender segregation were shared by the Guides. Both organizations held that gender mixing was “most undesirable” and that gender separation should be “strictly enforced” (178).

Woodcraft organizations formed in opposition to Scouts put mixed-gender camping at the heart of their project. Reassuring those who feared a loosening of morals as a result of intermingling, Evans noted, “the standard of behaviour in coeducational Woodcraft groups is remarkably high” (185). Any who engaged in sexual misconduct, Evans believed, would surely be expelled. He also noted, amusingly, that mixed camping is hardly “sexually exciting” (180). Should “morbid sex-cravings” emerge, the best solution, he proposed, is “an honourable love affair.” He even went so far as to suggest that a socially concerned and morally keen woodcrafter would make a more “devoted lover” (181).

In this, Evans was not advocating sex before marriage; that would be beyond the pale in organizations that courted, at least some of the time, public respectability. In Evans’s summaries, conventional approaches to marriage and parenthood were enshrined in woodcrafters’ eugenically informed attitudes to the development of the human race (in this context meaning the positive development of healthy bodies across generations rather than sterilization of the so-called “unfit”). For all of their relatively open-minded approaches to sex education and gender equality, Evans nonetheless expected woodcraft relationships to be “innocent” and chaste. Perhaps playfully, he concluded that it was possible for “the two sexes” to “camp in adjacent tents as safe from improper behaviour as though encased in iron armour and chained to the ground, they dwelt behind walls and locked doors in camps miles apart from one another and with an angel with a flaming sword standing between” (186). Despite Evans’s idealistic overview, sex education, gender segregation, and gender roles played out rather differently on the ground and under canvas in woodcraft organizations.

The Order of Woodcraft Chivalry

The Order of Woodcraft Chivalry was founded in 1916 by British Quakers. Ernest Westlake, an amateur geologist, and his son, Aubrey, a doctor and conscientious objector who had run Scout groups as a form of public war service, combined their shared interests in nature, progressive education, and classical poetry into an organization that they felt offered a more imaginative and less militaristic camp experience (Edgell). They did this by returning to the ideas of Ernest Thompson Seton, a British-born, American-resident youth leader whose turn-of-the-century Woodcraft Indians scheme had inspired Baden-Powell. The Order adapted elements from Seton to create a system that took the English knight rather than the Native American as its mythic ideal, and which included adults as well as children, and girls as well as boys. Based from 1920 at Sandy Balls, their private campground on the edge of the New Forest, the group’s colorful, ceremonial camp practices attracted thousands of members in the interwar years.

The group was committed to outdoor life, a belief in the capacity of children to self-govern, and a biologically inspired developmental model of recapitulation, popularized by child psychologist G. Stanley Hall. This scheme—shared in the 1920s by all woodcraft organizations—proposed that children should perform, or recapitulate, all successive stages of cultural evolution, from the undeveloped “primitive” to a “civilised” maturity. Order members developed distinctive schemes for the theory’s application, both in the progressive schools that were organized along woodcraft lines, and in their extensive literature. This was informed by intellectual inspirations from the “New Psychology” of Freud and Jung to Quakerism, the mystic science of Neo-Vitalism, classical myths, symbolism, and poetry. The Order believed that profound social, cultural and spiritual change was needed to correct the multiple ills of war-torn society. Militarism, materialism, and mass pleasures were destabilizing modern life and only a return to the best of the past could consolidate the new future they intended to shape. To this end, the Order designed folk-revival dress, regalia, and language to be used in group ceremonies and camps. These were structured not just to provide social gatherings but to model a new way of life.

As with all woodcraft organizations, camping was an essential transformational activity. Ernest Westlake argued that “civilisation”—modern, urban life—had made daily experience too comfortable (Edgell 72). Camping was a practical and moral re-education in simplicity and hardihood. Significantly, it was far from the corruption of the city, characterized as the root of all evil. Camping was also particularly important for young people. Order member Dorothy Revel argued, for example, “Motor cars, telephones, wireless sets, central heating, and other expensive adult luxuries are absolutely out of their place for children.” She argued, “They need to know the basic necessities of life [. . .]. They want earth-contact” (Woodcraft Discipline 14–15). A 1928 Order publication argued that camping was a symbolic ritual through which utopian ideals could be realized. Its author, Dr. H. D. Jennings White, noted, “I am a member of the Order of Wood-craft Chivalry because I see in it the germs of an organisation for the conscious creation of superhumanity” (13). This vision was a moral, physical, and spiritual rebirth; nothing less than “the creation of a new race of men here on earth, with the light of science in their eyes; with the love of beauty in their hearts; with order, control, and foresight in their actions; with a vitality and health in their bodies which we have never felt and can but dimly imagine; and with a spirit more tolerant, more daring, and more gracious than we shall ever have” (13).

Alongside its extensive writings on camping, the Order explored personal development. The membership was well-disposed to examine such issues as it boasted psychiatrists, medical practitioners, and radical educators among its leading figures. How these ideologies might be combined with children’s activities was hotly debated, particularly among more conservative members who saw the Order as a wholesome outdoor venture to implement new practical educational ideals, and the progressives who saw the Order as a crucible for radical life experiments. These debates crystallized around theories of nudism, sex reform, and sex education for children.

The first controversy focused on Harry “Dion” Byngham, a natural health journalist and mystic disciple of Blake, Whitman, and Nietzsche. Like many in the early days of the Order, Byngham was excited by the myths of the Ancient Greek Bacchae, whose ecst...