![]() Gaiman’s Brumous Boundaries and the Liminal Space

Gaiman’s Brumous Boundaries and the Liminal Space![]()

THE SHADOW OR THE SELF

The Construction of Neil Gaiman on Social Media

LANETTE CADLE

In addition to being a prolific and innovative author adept at multiple genres ranging from comics to television to novels, Neil Gaiman is a major presence on social media. Notice the verb is rather than has—social media done right creates a distinct identity, much in the way an author curates a complicated character, by selecting some details, obscuring others. Viviane Serfaty writes of this function in her book on blogging and early bloggers, The Mirror and the Veil, when she asserts that blogging “establishes a dialectical relationship between disclosure and secrecy, between transparency and opacity” (13), adding,

The paradox lies in the invisibility seemingly enjoyed on the Internet by both writers and readers. Thanks to the screen, diarists feel that they can write about their innermost feelings without feeling humiliation and identification, readers feel that they can inconspicuously observe others and derive increased understanding and power from that knowledge. (13)

Serfaty points out that “the very action of bringing something to light renders other areas even more opaque, so that the screen is transformed into a mirror onto which diary-writers project the signifiers of their identity in an ongoing process of deconstruction and reconstruction” (14). This should not be surprising. A good blogger is a good writer, and good writers select what they show and what they withhold. Neil Gaiman, if anything, is a superlative writer, one who is noted for creating multiple worlds across multiple genres, from the adult fiction of American Gods and Neverwhere to the mixed mythos of Sandman to the skewed children’s literature of The Graveyard Book. Even within that larger context, it could be said that Gaiman’s greatest creation is Neil Gaiman himself, aka @neilhimself, on Twitter as well as the other iterations of Gaiman on social media venues such as Instagram and his blog. Through these outlets, he manufactures a friendly and informative persona, one that reaches out to his readers and only wants to share, every bit as much as they want to know the real Neil Gaiman.

This chapter will closely examine Gaiman’s intensive use of social media to create a shadow self that gives fans the access they crave to his inner processes and daily life. This means making selections, much like a curator faced with a massive archive must select pieces that form a cohesive exhibit, a process that is much more nuanced than the commercial call to create a “brand,” an idea that is commonly touted within the world of business. Instead, it is a conscious construction of a shadow self, an embodiment that both is and is not the real Neil Gaiman.

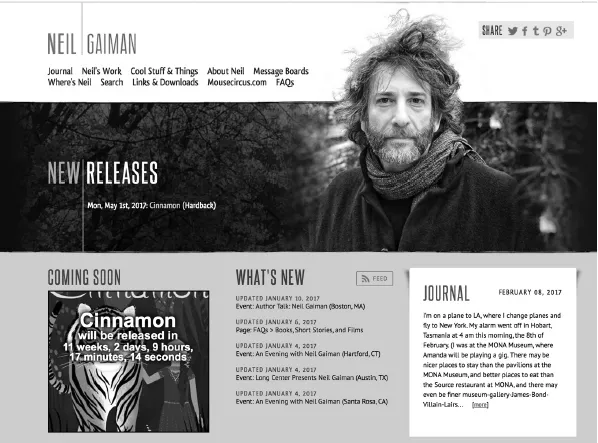

The Mechanics

Before discussing the implications of social media identity construction, it might be helpful to get an overview of the mechanics of social media as shown through Neil Gaiman’s example. It’s not surprising that the social media identity for Gaiman is one that readers want to share a journey with, and they do it in record numbers. Virtual Neil is hugely successful in the measure that counts most for social media—followers—because he gets the mechanics right. As of this writing, Gaiman follows 853 people on Twitter, down from 907 people a year ago, and has 2.59 million followers (as of June 6, 2017). Neil Gaiman, aka @neilhimself on Twitter, gives a unique view of an author’s life while artfully promoting his publications and appearances (Figure 9.1). In tandem with his tweets, he keeps a blog, which he calls a journal, that allows longer posts cross-promoted through his Twitter feed. Especially since the birth of his new son, Anthony (Ash), with wife Amanda Palmer, he increasingly uses Instagram.

The photos and occasional video document his daily life, the life that he summarizes on his blog, Facebook author page, and Twitter homepage as “[w] ill eventually grow up and get a real job. Until then, will keep making things up and writing them down.” This is a longstanding motto for Gaiman, one that interestingly shifts on his Instagram homepage to: “Writes things. Changes a baby. It’s a living.” Instagram has both photos and video, but Gaiman also has a YouTube channel that he uses far less, despite the fact that the medium has been used effectively by others for video blogging. He is only moderately active in other social media venues. For example, his Vimeo page has only a few entries, including his documentary, Dream Dangerously, which is available to rent or buy. Given the traditional film documentary form, albeit in a nontraditional marketing venue, this video biography is not really social media fodder. In the end, he seems to prefer Twitter, where followers have the advantage of seeing his tweets automatically in their Twitter feed, which may sound like Facebook’s newsfeed, but functions differently. It is more driven by information itself with the goal of retweets rather than how that information will coax written responses from “friends,” a major motivation on Facebook. The term Twitter uses instead, followers, shows the centrality of the tweets over individuals. Gaiman can and does have millions of followers on Twitter because their expectations are different than those for a Facebook friend. For new authors seeking to network within the publishing world, Facebook is unmatchable. Mentors, agents, support groups—it’s all there. Gaiman already has that though and is generous enough to use the other approach, Twitter, to gather up followers and let them into his world.

Figure 9.1. Neil Gaiman, Twitter homepage for @neilhimself. Twitter, Screenshot, 28 June 2016, 12:00 p.m. twitter.com/neilhimself.

Aside from Facebook and Twitter, Gaiman also uses his author blog/website for promotion. In general, blog posts are more flexible in purpose than tweets since they aren’t limited to 140 characters at a time, allowing for the long thoughts of identity construction to occur. His journal is where Twitter followers can “read more about it” by following a link from a tweet. As a form of older social media, blogs were here first and one by one, the functions blogs used to have are stripped away by newer social media that specialize—Twitter, for example. Blogs that had nothing but link posts used to be common, as were photo blogs, but those two types of blogs are now rare. Walker Rettberg agrees and gives Scripting News or Metafilter as examples of these early, link-heavy blogs (14). Though Gaiman keeps the blog that started it all and utilizes it as a repository for larger, more fully formed thoughts and opinions, for him it does not hold the central place Twitter does. Rather, Gaiman uses his Twitter account as his organizing hub, even though his blog dates back to 2001, seven years before his first tweet in December 2008. Although the blog may never shift back to being his central social media place, it remains, partially because of the ability of blogs to contain more complex text, the more full-bodied expression of Neil Gaiman the character, a creation that lives both inside and outside his comics and other print media.

Digital Identity or Just Identity

As an expression of a person, Gaiman’s online character generates a perceived divide between real vs. unreal, private vs. public. Fact: people are corporeal. They still have bodies and still have family and friends that they see almost every day. They touch—they can brush a stray hair from a shoulder or be pained by the off-key whistling that sometimes accompanies a man’s morning shave or smell the pungent scent of Barbasol. Bodies aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. This is the private self.

Along with that vision of embodiment, there is also a long history of the idea of writing as a body of work or even writing as the body enscribed. Easily the most central of these theories is that of Hélène Cixous and her concept of ecriture feminine, best stated in her essay, “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Granted, Cixous writes about what she initially positions as women’s writing, but later work, especially that by Judith Butler, complicates the idea of defining a certain type of writing as being sexed, with Butler’s important distinction between sex and gender in Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity marking the change.

This concept of embodied writing has merit when considering Gaiman’s use of social media for two reasons. First, Gaiman has been critically positioned as a feminist author.1 Feminist theory, especially feminist writing theory, is full of metaphors that pair writing and the body and even writing inscribing the body. In “Speaking the Cacophony of Angels: Gaiman’s Women and the Fracturing of Phallocentric Discourse,” Rachel R. Martin notes that Gaiman’s feminism is a planned and conscious practice rather than a theoretical stance only, that it “entices and draws in female readers through his inclusion of feminine lead characters” (11), a definite break from the past for the world of comics especially. This is not theoretical feminism; this is feminism in action and a necessary part of Gaiman’s writerly identity. At the same time, when speaking of ecriture feminine, Cixous declares her vision for the individual when she states that “[s] he must write her self” (880), keeping that space between the terms her and self to show who is writing what. She goes on to detail why this is necessary, noting that “[b]y writing her self, woman will return to the body which has been more than confiscated from her” and that this writing “will always surpass the discourse that regulates the phallocentric system” (883), a very similar idea to Martin’s claim that Gaiman’s effectiveness as a writer owes much to his “feminine narratives” that break up what would otherwise be a more canonical, “phallocentric” approach (11). That said, his use of writing as the construction of a body makes sense as a sound feminist practice; taken a step further to the multimodal (text, image, audio, video) approach used in social media, Gaiman’s social media empire becomes a body with Twitter as its circulatory system.

Returning to reasons why the social media Gaiman is an embodied composition, the second reason to consider this concept of embodied writing is the nature of social media itself. Done right, it grows. It is not static like print. When done long enough and done well, the result is what Neil Gaiman has: a body constructed of words and light that becomes more real to his followers than many of their next-door neighbors. That, of course, leaves the whole concept of real vs. not-to-be –dealt-with, as well as how readers value one against the other. In her 1999 book, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics, N. Katherine Hayles complicates the flesh/not-flesh dichotomy with her concept of the posthuman. For Hayles, embodiment is both pixels and flesh, and her analysis of what that means foreshadows social media, where it is possible to have “friends” over a number of years that you may never see IRL (in real life). For Hayles, “the posthuman view privileges informational pattern over material instantiation” (2). This leads to body-housed consciousness seen as less definitive, with the body seen as “the original prosthesis” (3).

Finally, and what Hayles views as the most important feature,

the posthuman view configures human being so that it can be seamlessly articulated with intelligent machines. In the posthuman, there are no essential differences or absolute demarcations between bodily existence and computer simulation, cybernetic mechanism and biological organism, robot teleology and human gods. (3)

Of course, in 1999, blogs were new, and Twitter was still a little less than ten years away. Nonetheless, Hayles’s concept of the posthuman predicts the function of social media, that of expansion of the body rather than an erasure of the body. Not every person who uses social media takes it this far, but given enough time and skill, it is possible. Gaiman has the advantage of being active on social media from the very beginning of blogging, with his current blog listing archives as far back as September 2001. Add to that his status within science fiction and fantasy literature, and social media becomes a part of a holistic embodiment, not one end of a “bodily existence and computer simulation” (3) binary.

The Shadow Self

Neil Gaiman is far from the only author with an online presence and not all authors take this concept of an embodied posthuman self so far. Sometimes it’s just about marketing. Companies and products market themselves every day through social media with varying degrees of success. Their “why” is clear: to sell more and to create brand loyalty. When it comes to authors, though, the reasons are not as clear-cut. A creative aspect can come into play. It’s true that for most literary authors, Facebook, a professional site, and Twitter are increasingly important. Authors are expected to shoulder a large part of their book’s promotion themselves, and the ones with the fewest resources, beginning authors, are expected to carry the largest share of their promotion—creating the author website, setting up bookstore appearances, readings, and at times, even soliciting presales from individuals and stores. Though Gaiman goes to where the money is, in this case, where the readers, viewers, concertgoers, and other consumers of the world of Gaiman can be found on social media, his work is more nuanced than that and the persona he crafts online is no exception (Figure 9.2). Granted, Gaiman still keeps a brisk personal appearance pace, but when he can’t, during the times when he is actually working on a writing project for example, social media keeps him visible.

Figure 9.2. Neil Gaiman, blog and homepage. neilgaiman.com, screenshot, 10 February 2017.

With so many years of archives, virtual Neil is so complete that his identity constructed through social media does not “feel” artificial, even though he has an assistant to schedule and at times implement the posts. This does not seem to reduce the personal “feel” to his posts. Which tweets or posts are from an assistant and which are Gaiman’s never seems to be an issue. This blurring between reality and constructed reality—or as Jill Walker Rettberg asks in Seeing Ourselves through Technology, “people or texts?” (11)—is typical of social media, the place where people construct identities for themselves through selfies, links, and snippets of information. Gaiman compounds that by using visual rhetoric well—i.e., persuasion done through images, including selfies, and something only an author can bring, the imagined and actual images created by his work. Thus far it is strictly promotion albeit for a good cause, but he goes further with teasers and photos that make it more when he adds,

And I will do my own bit for it. I will put up something unique to this blog. Probably you are thinking, will he write about his time on the Red Carpet at Cannes for HOW TO TALK TO GIRLS AT PARTIES? It is not that. (But here are costume designer Sandy Powell, channeling Ziggy Stardust, and star Elle Fanning eating colour-coordinated macaroons.) Perhaps you are thinking, Will he perhaps post photographs of Gillian Anderson as Media in the next episode of American Gods incarnated as Ziggy Stardust also eating colour-coordinated macaroons? I will not. I do not believe such photos exist. Instead I will put up photos of my elf-child, Ash. I will see him on Saturday, and the Cannes red carpet would have been much more fun if he had been on it.

Of course, he intersperses these teasers with photos as described. The photo of Gillian Anderson as Ziggy Stardust is especially compelling and not a publicity still (Figure 9.3). It is a candid shot, one hauntingly evocative of the young Bowie. Of the photos of his son Ash, two are close-ups, one is a father-and-son photo, and another is of Ash laying on a bed reading. He ends the post with a schedule of upcoming appearances. On the surface, this may seem like (and at some level is) promotion, plain and simple. However, the strength of this collection of details through multiple media is not in the individual pieces, but in the massively detailed portrait it builds using an archive that literall...