- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Rheology is primarily concerned with materials: scientific, engineering and everyday products whose mechanical behaviour cannot be described using classical theories. From biological to geological systems, the key to understanding the viscous and elastic behaviour firmly rests in the relationship between the interactions between atoms and molecules and how this controls the structure, and ultimately the physical and mechanical properties. Rheology for Chemists An Introduction takes the reader through the range of rheological ideas without the use of the complex mathematics. The book gives particular emphasis on the temporal behaviour and microstructural aspects of materials, and is detailed in scope of reference. An excellent introduction to the newer scientific areas of soft matter and complex fluid research, the second edition also refers to system dimension and the maturing of the instrumentation market. This book is a valuable resource for practitioners working in the field, and offers a comprehensive introduction for graduate and post graduates. "... well-suited for self-study by research workers and technologists, who, confronted with technical problems in this area, would like a straightforward introduction to the subject of rheology." Chemical Educator, "... full of valuable insights and up-to-date information." Chemistry World

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1.1 DEFINITIONS

1.1.1 Stress and Strain

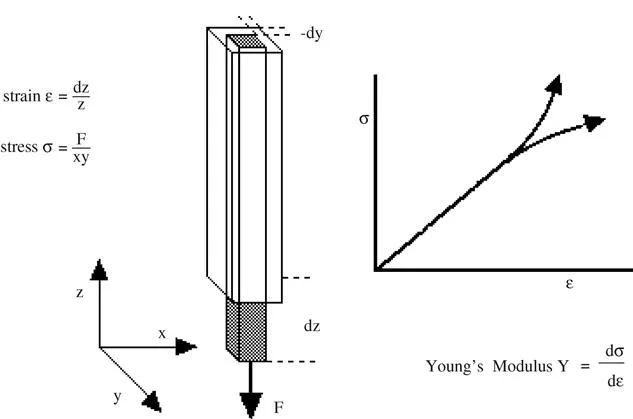

- The elastic modulus is constant at small stresses and strains. This linearity gives us Hooke’s law,1 which states that the stress is directly proportional to the strain.

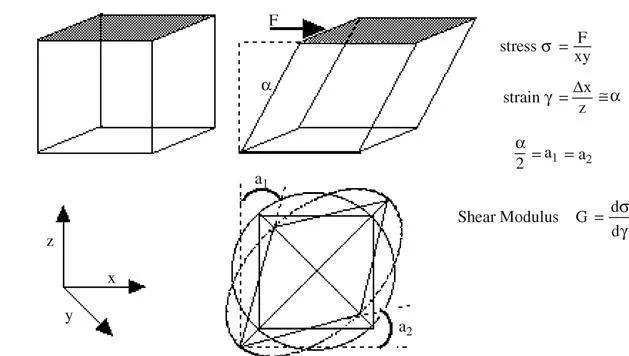

- The shear strain, produced by the application of a shear stress σ, is illustrated in Figure 1.2. The lower section of the figure shows the general case where there is no rotation of the principal axes of strain. These are simply the diagonals of the material element, one of which shortens whilst the other lengthens. We will see later how this leads to compressive and extensional forces on pairs of particles as they collide in a flowing system.

- At high stresses and strains, nonlinearity is observed. Strain hardening (an increasing modulus with increasing strain up to fracture) is normally observed with polymeric networks. Strain softening is observed with some metals and colloids until yield is observed.

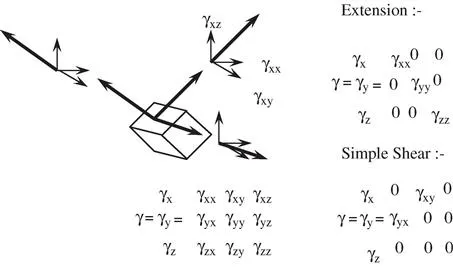

- We should recognise that stress and strain are tensor quantities and not scalars. This will not present any difficulties in this text but we should bear it in mind as the consequences can be dramatic and can be useful. To illustrate the mathematical problem, we can think what happens when we apply a strain to an element of our material. The strain is made up of three orthogonal components that can be further subdivided into components, each of which are lined up with our axes. This is shown in Figure 1.3.

1.1.2 Rate of Strain and Flow

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Elasticity: High Deborah Number Measurements

- Chapter 3 Viscosity: Low Deborah Number Measurements

- Chapter 4 Linear Viscoelasticity I: Phenomenological Approach

- Chapter 5 Linear Viscoelasticity II: Microstructural Approach

- Chapter 6 Nonlinear Responses

- Subject Index