![]()

CHAPTER 1

Railways without Chemists?

This chapter addresses the problem of emerging railways in Britain for which chemistry appeared to be irrelevant. We now know that this was an illusion. There were obvious ways in which chemistry owed much to railways, however, the debt owed by the railways to chemistry is almost completely unknown. The growth of the railway enthusiast movement makes this current lack of awareness all the more puzzling.

The nineteenth century has often been called “The Age of the Railway”. It saw the birth of locomotive-hauled railway trains, and the coming of the public railways was one of the most powerful instruments of massive social change that had yet appeared. The subsequent story is mainly confined to Britain, for that is where much of the action took place. The Victorian railway has indeed been the subject of innumerable books, far too many to mention, but by way of example is one splendidly summarised by its title: Railways and the Victorian Imagination.1 Book after book has appeared glamorising the achievements of “the iron road”. Indeed, railways touched on most of life at some time. They gave the population a new mobility and a fresh availability of goods from faraway places. They moved coal from its mines to millions of homes, they were largely responsible for the establishment of the annual seaside holiday, and they made possible the mass movement of livestock, even including whole circuses. Railways, alongside heavy manufacture and textile production, are a superb example of the dawning of a new technology which transformed society, and, being individual examples of private enterprise, spawned a huge propaganda industry. Railways are portrayed as (amongst other things) a product of consummate engineering skills, but almost nowhere is there even a mention of indebtedness to any of the sciences, least of all chemistry. Its conspicuous absence from railway propaganda has materially assisted in the belief that it was irrelevant if not totally absent.

At the same time as this happened, Victorian Britain saw what might justifiably called a second “scientific revolution”. It was not as far-reaching as the so-called “Scientific Revolution” of the 17th century, but it was important nonetheless. Immense advances took place in some of the older sciences that had long-term effects on chemistry and on technology itself. Alongside electricity, chemistry itself exploded with new ideas, and it would have been surprising if the railway industry had been unaffected. An even bigger surprise lies in the wholesale ignorance as to whether this is the case or not. It is a contention of this book that the unexpected did happen, that railways were affected by chemistry, and that without chemistry the railways would not have existed as we know them, or at least they would have been unimaginably different.

There were, of course, some obvious ways in which the opposite trend was true, and chemistry has been heavily beholden to the railway industry. It had often been alleged that the science owed more to railways than vice versa. Thermodynamics was indebted to some pioneering studies of the steam engine (though it must be said that most of these early steam engines were of the stationary type, and in many cases had nothing to do with rail traction as such). All this is commonplace. There were other interactions, however, as may be seen exemplified by several well-documented rail journeys by chemists in the 19th century.

At 9.20 am (or as near as possible) on an October morning of 1845, a train of yellow coaches steamed slowly southwards out of Lancaster, the only through train that day to London (Euston). The Lancaster & Preston Railway was conveying among its passengers, a young man, Edward Frankland, who had just completed his apprenticeship in a local chemist’s shop (see Figure 1.1). He had had his head stuffed full of new ideas about chemical theory which he had picked up at unofficial evening classes in Lancaster run by two philanthropic doctors. This was the science for him, and one of his benefactors had managed to obtain the promise of work in the Department of Woods and Forests, based in Westminster and headed by the aspiring young chemist, Lyon Playfair, born a mere seven years before Frankland himself.

Figure 1.1 Edward Frankland (1825–1899).

The next five years saw many changes for Frankland, but included the foundation of organometallic chemistry and the first glimpses of a theory of valency, one of the most basic features of chemical thought, both then and now. They also witnessed his acquisition of a Marburg PhD, and the start of a meteoric career that was destined to revolutionise chemistry itself. One remarkable thing was that it all began with that railway journey from Lancaster.2 Indeed, there was no other practical means of transport that did not take several days, and in later years it was the newly formed network of railways in Britain that made possible the holding of provincial conferences by such organizations as the Chemical Society and the British Association for the Advancement of Science. All science thus profited by railway travel but, if a science is in a state of massive flux as was chemistry, meetings between kindred minds become imperative. In that sense, as we shall see again, chemistry in Britain was peculiarly indebted to the railways. As for Frankland himself, while his vitally important contributions to chemistry are well known, knowledge of his important work for the railway industry has only recently come to light (see Chapters 4 and 5). Yet there is further evidence from overseas as we shall now see.

By 1860, chemistry was in a condition that can only be described as “dreadful”. To no one was this more apparent than August Kekulé, professor of chemistry at Ghent and famous for his later hexagon formula for benzene, but whose textbook on organic chemistry gave no less than 19 formulae for one compound, acetic acid. Partly this was a reflection of confusion regarding atomic weights. Accordingly, Kekulé conceived an international conference at the eastern town of Karlsruhe in order to resolve the matter. Unfortunately it was largely unsuccessful, though an Italian delegate, Stanislao Cannizzaro, did propose a solution though it is perhaps too technical to describe here. As delegates left after a few days wrangling, Cannizzaro presented them with a copy of his own course of chemistry which contained this solution. One of the delegates, Lothar Meyer, pocketed a copy “to read on the way home”. He was returning to Breslau in the far east of the country (now in Poland and known as Wroclaw). Today travellers fly easily between the two cities, and although we do not know Meyer’s exact method of travel, it almost certainly included a long journey by rail. He had time to read and re-read the paper, and he gradually perceived its value. As he said “the scales seemed to fall from my eyes. Doubts disappeared and a feeling of quiet certainty took their place”.3 The discovery was enshrined in his textbook, Die Modernen Theorien der Chemie, an influential work written two years later. Whether this enlightenment actually began in a railway carriage, and was completed at home, we cannot be sure. The conference itself, one of the first international conferences of any science, could never have been possible, however, without the burgeoning railway network all over Europe.4 As a recent scholar has observed, “the steamboat, railway and the telegraph did much to facilitate the formation of national and international communities in science, including those in chemistry”.5 For that reason alone – and there are many others – the debt of chemistry to the railways is immense.

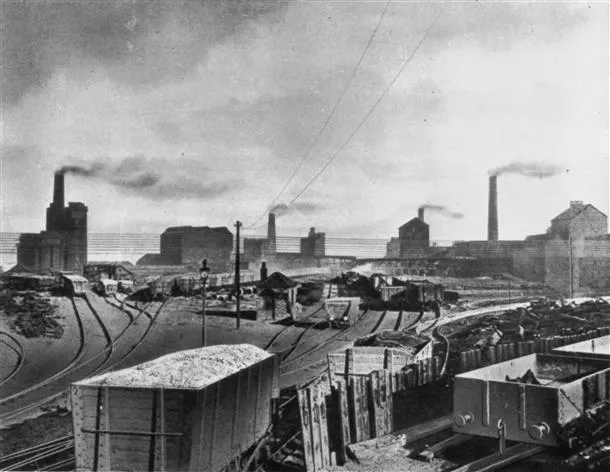

In terms of transit, the growing chemical industry was often reliant on the railways for transport of raw materials (see Figure 1.2) as well as people, though much material was also conveyed by sea or canal. Chemical plants were sometimes served by trains hauled by “fireless” locomotives, well filled with steam but having no fire to replenish them or to ignite flammable material nearby. Service of chemistry by railways continued. In the USA, railways were for many years almost the only long-distance carriers of iron, salt and gunpowder, and they continue to play an important role today. This is true of many industrialised countries in the latter part of the 19th century.

Figure 1.2 Allhusen Works, Gateshead, 1907, showing the railway lines serving the chemical company. With permission from Gateshead Council, Libraries and Arts, Gateshead Central Library.

This book focuses on “traffic” in the other direction, i.e. chemistry in the service of the railways. For most people, the two are unrelated. Railways today have a huge enthusiast following. Thousands of people, mainly men and boys, maintain intense interest in railway practice and performance, and the steam engine, though banned for regular service by British Rail in 1968, still exerts an almost fanatical fascination. Not all of these aficionados wear anoraks! Many of them have a detailed knowledge that never ceases to astonish. They display a pre-nationalisation enthusiasm that once supported individual railways, fanned into even greater fervour by pre-war books like the Boys of all Ages series by W. G. Chapman for the Great Western Railway. This series of books contained an incredible amount of technical detail on all aspects of railway operation and sold over 100000 copies.6 The first in the series came out in August, 1927. Nor is there any shortage of relevant literature today, with many periodicals, of which the old-established Railway Magazine tops the list. As we write this book, a major manufacturing venture has recently completed work on a new A1 Pacific (4-6-2) steam engine, Tornado, to a design by A. H. Peppercorn from just after the war (see Figure 1.3). The manufacture was brilliantly successful. It is intended that it will be used for main line steam haulage of “special” trains, like its Peppercorn predecessors in regular service.7 Indeed, the first year of service of the steam engine gives every indication that this goal will be fulfilled.

Figure 1.3 Tornado, a new locomotive produced to a previous design, on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway in April 2011. Photography by P. Benham.

Chemistry can never claim anything like the place of affection accorded to railways, but it has served them in one spectacular way, in occasionally providing the explosive needed for railway cuttings and tunnels. Most of this work was manual, or with mechanised diggers, while tunnels used various “shields”. Since the beginning, however, these processes have occasionally been helped by gunpowder, a product of chemical investigations from many centuries earlier, containing the chemicals sulfur, charcoal and saltpetre. In 1865, Alfred Nobel invented dynamite, nitroglycerin absorbed on kieselguhr. Dynamite was applied in the boring of the Mont Cénis tunnel, joining France and Italy, in 1869, and led to a five-fold reduction in time compared with the use of gunpowder.8 Unfortunately, the discovery of dynamite was a little too late to be of use in Britain, having occurred just after the greatest period of railway expansion.

Today chemistry has lost much of its popular glamour. Partly this is because it is much more complex and the new practical applications are rather less obvious than before (except in medicine and allied fields). For one thing, it is now a profession, with trained and highly skilled chemists being paid to do it, so experiments by unrecognised “amateurs” are rightly frowned upon. For another, it is a well-established school subject, and few things diminish affection so much as having to learn them!

However, it was not always thus, and the popularity of chemical science knew no bounds in the 19th century. Again, in those days, it was mainly men and boys who went to the greatest lengths to study the subject in such limited spare time as they had. It was so popular that when “science” was mentioned in connection with government exams it almost always meant chemistry. There were reasons for this. First of all chemistry was widely seen as a “useful subject”, and one that could benefit mankind by improving working conditions in a multitude of ways. It was incidentally the belief in the power of science and technology that helped to make Britain such a powerful manufacturing nation: “the workshop of the world”. Chemistry was also seen as an exciting subject, with fires, explosions and odours of all kinds. Not for nothing did Victorian schoolboys call it “stinks”!

More seriously, today the combined efforts of security authorities and compliant teachers have meant that many of the most spectacular experiments are no longer demonstrated in the lab. What is left is much “tamer” and less likely to set the pulses racing (this, by the way, is about popular perceptions, not what real chemistry is actually about).

All of this means that to talk of railways and chemistry in the same breath suggests a certain incongruity, and a connection that in most people’s minds has never been made. Yet, as we have mentioned, we believe that without application of chemistry the railways of Britain would be almost unrecognisable today. Subsequent chapters will explore why this should be so, not least by demonstrating that water (for steam engines) had to be analysed so as to improve boiler efficiency and reduce maintenance costs. Chemistry also pronounced on the difference between cast iron, steel and wrought iron, so important for all kinds of engineering, not least the production of rails.

Such a claim is so far-reaching that it is easy to dismiss it without further thought. A vast amount of new evidence has appeared in the last few years, however, which substantiates our assertion. It came about in the following way.

For some years a detailed investigation into the origins of the chemical profession had suggested that chemical analysis was important for many things, including early railways.9 Then a chance encounter led one of us [CAR] to explore the matter more fully. Most important was the input of the late Mr. Mike Hall. He was then area chemist at a railway laboratory at Crewe, set up over a century earlier by the London and North Western Railway. Mr. Hall had had unrivalled access to documents about his laboratory, stretching back to its foundation. Amongst the treasures in the Hall collection was a number of laboratory notebooks, several pho...