- 303 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Naturalist In La Plata

About this book

"The Naturalist In La Plata" is a collection of essays by Argentinian naturalist William Henry Hudson, first published in 1895. They primarily concern the Pampas, an area in the South American lowlands where Hudson grew up, and constitute a masterful blend of scientific content and interesting stories, anecdotes, and other titbits from his observations of the area. Contents include: "The Desert Pampas", "Cub Puma, Or Lion Of America", "Wave Of Life", "Some Curious Animal Weapons", "Fear In Birds Parental And Early Instincts", "The Mephitic Skunk", "Mimicry And Warning Colours In Grasshoppers", "Dragon-fly", "Storms", and "Mosquitoes And Parasite Problems". William Henry Hudson (1841 - 1922) was an Argentinian naturalist, author, and ornithologist. He was one of the founding members of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, and is best known for his novel "Green Mansions" (1904). Other notable works include "A Crystal Age" (1887) and "Far Away and Long Ago" (1918), which has since been adapted into a film. Many vintage books such as this are becoming increasingly scarce and expensive. We are republishing this volume now in an affordable, modern, high-quality edition complete with a specially commissioned new biography of the author.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Naturalist In La Plata by William Henry Hudson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER XIX.

MUSIC AND DANCING IN NATURE.

IN reading books of Natural History we meet with numerous instances of birds possessing the habit of assembling together, in many cases always at the same spot, to indulge in antics and dancing performances, with or without the accompaniment of music, vocal or instrumental.; and by instrumental music is here meant all sounds other than vocal made habitually and during the more or less orderly performances; as, for instance, drumming and tapping noises; smiting of wings; and humming, whip-cracking, fan-shutting, grinding, scraping, and horn-blowing sounds, produced as a rule by the quills.

There are human dances, in which only one person performs at a time, the rest of the company looking on; and some birds, in widely separated genera, have dances of this kind. A striking example is the Rupicola, or cock of-the-rock, of tropical South America. A mossy level spot of earth surrounded by bushes is selected for a dancing-place, and kept well cleared of sticks and stones; round this area the birds assemble, when a cock-bird, with vivid orange-scarlet crest and plumage, steps into it, and, with spreading wings and tail, begins a series of movements as if dancing a minuet; finally, carried away with excitement, he leaps and gyrates in the most astonishing manner, until, becoming exhausted, he retires, and another bird takes his place.

In other species all the birds in a company unite in the set performances, and seem to obey an impulse which affects them simultaneously and in the same degree; but sometimes one bird prompts the others and takes a principal part. One of the most curious instances I have come across in reading is contained in Mr. Bigg-Wither's Pioneering in South Brazil. He relates that one morning in the dense forest his attention was roused by the unwonted sound of a bird singing--songsters being rare in that district. His men, immediately they caught the sound, invited him to follow them, hinting that he would probably witness a very curious sight. Cautiously making their way through the dense undergrowth, they finally came in sight of a small stony spot of ground, at the end of a tiny glade; and on this spot, some on the stone and some on the shrubs, were assembled a number of little birds, about the size of tom-tits, with lovely blue plumage and red top-knots. One was perched quite still on a twig, singing merrily, while the others were keeping time with wings and feet in a kind of dance, and all twittering an accompaniment. He watched them for some time, and was satisfied that they were having a ball and concert, and thoroughly enjoying themselves; they then became alarmed, and the performance abruptly terminated, the birds all going off in different directions. The natives told him that these little creatures were known as the "dancing birds."

This species was probably solitary, except when assembling for the purpose of display; but in a majority of cases, especially in the Passerine order, the solitary species performs its antics alone, or with no witness but its mate. Azara, describing a small finch, which he aptly named Oscilador, says that early and late in the day it mounts up vertically to a moderate height; then, flies off to a distance of twenty yards, describing a perfect curve in its passage; turning, it flies back over the imaginary line it has traced, and so on repeatedly, appearing like a pendulum swung in space by an invisible thread.

Those who seek to know the cause and origin of this kind of display and of song in animals are referred to Darwin's Descent of Man for an explanation. The greater part of that work is occupied with a laborious argument intended to prove that the love-feeling inspires the animals engaged in these exhibitions, and that sexual selection, or the voluntary selection of mates by the females, is the final cause of all set musical and dancing performances, as well as of bright and harmonious colouring, and of ornaments.

The theory, with regard to birds is, that in the love-season, when the males are excited and engage in courtship, the females do not fall to the strongest and most active, nor to those that are first in the field; but that in a large number of species they are endowed with a faculty corresponding to the aesthetic feeling or taste in man, and deliberately select males for their superiority in some aesthetic quality, such as graceful or fantastic motions, melody of voice, brilliancy of colour, or perfection of ornaments. Doubtless all birds were originally plain-coloured, without ornaments and without melody, and it is assumed that so it would always have been in many cases but for the action of this principle, which, like natural selection, has gone on accumulating countless small variations, tending to give a greater lustre to the species in each case, and resulting in all that we most admire in the animal world--the Rupicola's flame-coloured mantle, the peacock's crest and starry train, the joyous melody of the lark, and the pretty or fantastic dancing performances of birds.

My experience is that mammals and birds, with few exceptions--probably there are really no exceptions--possess the habit of indulging frequently in more or less regular or set performances, with or without sound, or composed of sound exclusively; and that these performances, which in many animals are only discordant cries and choruses, and uncouth, irregular motions, in the more aerial, graceful, and melodious kinds take immeasurably higher, more complex, and more beautiful forms. Among the mammalians the instinct appears almost universal; but their displays are, as a rule, less admirable than those seen in birds. There are some kinds, it is true, like the squirrels and monkeys, of arboreal habits, almost birdlike in their restless energy, and in the swiftness and certitude of their motions, in which the slightest impulse can be instantly expressed in graceful or fantastic action; others, like the Chinchillidae family, have greatly developed vocal organs, and resemble birds in loquacity; but mammals generally, compared with birds, are slow and heavy, and not so readily moved to exhibitions of the kind I am discussing.

The terrestrial dances, often very elaborate, of heavy birds, like those of the gallinaceous kind, are represented in the more volatile species by performances in the air, and these are very much more beautiful; while a very large number of birds--hawks, vultures, swifts, swallows, nightjars, storks, ibises, spoonbills, and gulls--circle about in the air, singly or in flocks. Sometimes, in serene weather, they rise to a vast altitude, and float about in one spot for an hour or longer at a stretch, showing a faint bird-cloud in the blue, that does not change its form, nor grow lighter and denser like a flock of starlings; but in the seeming confusion there is perfect order, and amidst many hundreds each swift- or slow-gliding figure keeps its proper distance with such exactitude that no two ever touch, even with the extremity of the long-wings, flapping or motionless:--such a multitude, and such miraculous precision in the endless curving motions of all the members of it, that the spectator can lie for an hour on his back without weariness watching this mystic cloud-dance in the empyrean.

The black-faced ibis of Patagonia, a bird nearly as large as a turkey, indulges in a curious mad performance, usually in the evening when feeding-time is over. The birds of a flock, while winging their way to the roosting-place, all at once seem possessed with frenzy, simultaneously dashing downwards with amazing violence, doubling about in the most eccentric manner; and when close to the surface rising again to repeat the action, all the while making the air palpitate for miles around with their hard, metallic cries. Other ibises, also birds of other genera, have similar aerial performances.

The displays of most ducks known to me take the form of mock fights on the water; one exception is the handsome and loquacious whistling widgeon of La Plata, which has a pretty aerial performance. A dozen or twenty birds rise up until they appear like small specks in the sky, and sometimes disappear from sight altogether; and at that great altitude they continue hovering in one spot, often for an hour or longer, alternately closing and separating; the fine, bright, whistling notes and flourishes of the male curiously harmonizing with the grave, measured notes of the female; and every time they close they slap each other on the wings so smartly that the sound can be distinctly heard, like applauding hand-claps, even after the birds have ceased to be visible.

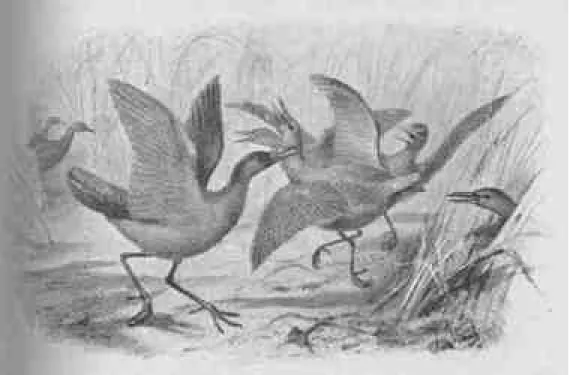

The rails, active, sprightly birds with powerful and varied voices, are great performers; but owing to the nature of the ground they inhabit and to their shy, suspicious character, it is not easy to observe their antics. The finest of the Platan rails is the ypecaha, a beautiful, active bird about the size of the fowl. A number of ypecahas have their assembling place on a small area of smooth, level ground, just above the water, and hemmed in by dense rush beds. First, one bird among the rushes emits a powerful cry, thrice repeated; and this is a note of invitation, quickly responded to by other birds from all sides as they hurriedly repair to the usual place. In a few moments they appear, to the number of a dozen or twenty, bursting from the rushes and running into the open space, and instantly beginning the performance. This is a tremendous screaming concert. The screams they utter have a certain resemblance to the human

Dance of Ypecaha Bails.

voice, exerted to its utmost pitch and expressive of extreme terror, frenzy, and despair. A long, piercing shriek, astonishing for its vehemence and power, is succeeded by a lower note, as if in the first the creature had well nigh exhausted itself: this double scream is repeated several times, and followed by other sounds, resembling, as they rise and fall, half smothered cries of pains and moans of anguish. Suddenly the unearthly shrieks are renewed in all their power. While screaming the birds rush from side to side, as if possessed with madness, the wings spread and vibrating, the long-beak wide open and raised vertically. This exhibition lasts three or four minntes, after which the assembly peacefully breaks up.

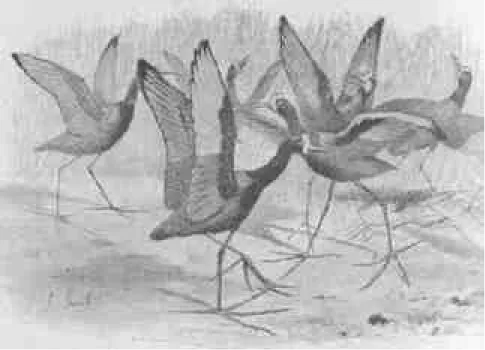

The singular wattled, wing-spurred, and long-, toed jacana has a remarkable performance, which seems specially designed to bring out the concealed

Wing-display of Jacanas.

beauty of the silky, greenish-golden wing-quills-The birds go singly or in pairs, and a dozen or fifteen individuals may be found in a marshy place feeding within sight of each other. Occasionally, in response to a note of invitation, they all in a moment leave off feeding and. fly to one spot, and, forming a close cluster, and emitting short, excited, rapidly repeated notes, display their wings, like beautiful flags grouped loosely together: some hold the wings up vertically and motionless; others, half open and vibrating rapidly, while still others wave them up and down with a slow, measured motion.

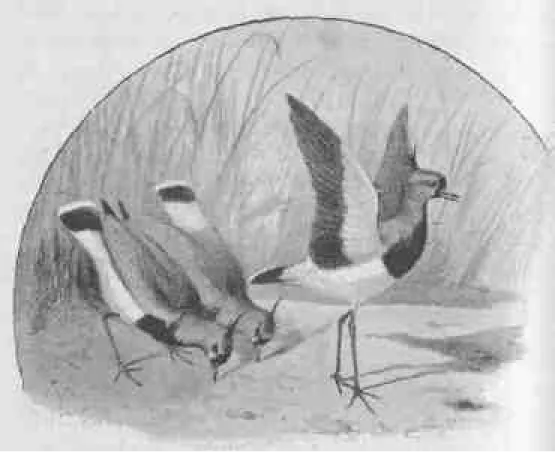

In the ypecaha and jacana displays both sexes take part. A stranger performance is that of the spur-winged lapwing of the same region--a species resembling the lapwing of Europe, but a third larger, brighter coloured, and armed with spurs. The lapwing display, called by the natives its "dance," or "serious dance"--by which they mean square dance--requires three birds for its performance, and is, so far as I know, unique in this respect. The birds are so fond of it that they indulge in it all the year round, and at frequent intervals during the day, also on moonlight nights. If a person watches any two birds for some time--for they live in pairs--he will see another lapwing, one of a neighbouring couple, rise up and fly to them, leaving his own mate to guard their chosen ground; and instead of resenting this visit as an unwarranted intrusion on their domain, as they would certainly resent the approach of almost any other bird, they welcome it with notes and signs of pleasure. Advancing to the visitor, they place themselves behind it; then all three, keeping step, begin a rapid march, uttering resonant drumming notes in time with their movements; the notes of the pair behind being emitted in a stream, like a drum-roll, while the leader utters loud single notes at regular intervals. The march ceases; the leader elevates his wings and stands erect and motionless, still uttering loud notes; while the other two, with puffed-out plumage and standing exactly abreast stoop forward and downward until the tips of their beaks touch the ground, and, sinking their rhythmical voices to a murmur, remain for some time in this posture. The performance is then over and the visitor goes back to his own ground and mate, to receive a visitor himself later on.

Dance of Spur-winged Lapwings.

In the Passerine order, not the least remarkable displays are witnessed in birds that are not accounted songsters, as they do not possess the highly developed vocal organ confined to the suborder Oscines. The tyrant-birds, which represent in South America the fly-catchers of the Old World, all have displays of some kind; in a vast majority of cases these are simply joyous, excited duets between male and female, composed of impetuous and more or less confused notes and screams, accompanied with beating of wings and other gestures. In some species choruses take the place of duets, while in others entirely different forms of display have been developed. In one group--Cnipolegus--the male indulges in solitary antics, while the silent, modest-coloured female keeps in hiding. Thus, the male of Cnipolegus Hudsoni, an intensely black-plumaged species with a concealed white wing-band, takes his stand on a dead twig on the summit of a bush. At intervals he leaves his perch, displaying the intense white on the quills, and producing, as the wings are thrown open and shut alternately, the effect of successive flashes of light. Then suddenly the bird begins revolving in the air about its perch, like a moth wheeling round and close to the flame of a candle, emitting a series of sharp clicks and making a loud humming with the wings. While performing this aerial waltz the black and white on the quills mix, the wings appearing like a grey mist encircling the body. The fantastic dance over, the bird drops suddenly on to its perch again; and, until moved to another display, remains as stiff and motionless as a bird carved out of jet.

The performance of the scissors-tail, another tyrant-bird, is also remarkable. This species is grey and white, with black head and tail and a crocus-yellow crest. On the wing it looks like a large swallow, but with the two outer tail-feathers a foot long. The scissors-tails always live in pairs, but at sunset several pairs assemble, the birds calling excitedly to each other; they then mount upwards, like rockets, to a great height in the anand, after wheeling about for a few moments, pro-cipitate themselves downwards with amazing violence in a wild zigzag, opening and shutting the long tail-feathers like a pair of shears, and producing loud whirring sounds, as of clocks being wound rapidly up, with a slight pause after each turn of the key. This aerial dance over, they alight in separate couples on the tree tops, each couple joining in a kind of duet of rapidly repeated, castanet-like sounds.

The displays of the wood-hewers, or Dendrocolap-tidae, another extensive family, resemble those of the tyrant-birds in being chiefly duets, male and female singing excitedly in piercing or resonant voices, and with much action. The habit varies somewhat in the cachalote, a Patagonian species of the genus Ho...

Table of contents

- William Henry Hudson

- PREFACE.

- THE DESERT PAMPAS.

- THE PUMA, OB LION OF AMERICA.

- A WAVE OF LIFE,

- SOME CURIOUS ANIMAL WEAPONS.

- FEAR IN BIRDS.

- PARENTAL AND EARLY INSTINCTS.

- THE MEPHITIC SKUNK.

- MIMICRY AND WARNING COLOURS IN GRASSHOPPERS.

- DRAGON-FLY STORMS.

- MOSQUITOES AND PARASITE PROBLEMS.

- HUMBLE-BEES AND OTHER MATTERS.

- A NOBLE WASP.

- NATURE'S NIGHT LIGHTS. (Remarks about Fireflies and other matters.)

- FACTS AND THOUGHTS ABOUT SPIDERS.

- THE DEATH-FEIGNING INSTINCT.

- HUMMING-BIRDS.

- THE CRESTED SCREAMER.

- THE WOODHEWER FAMILY.

- MUSIC AND DANCING IN NATURE.

- BIOGRAPHY OF THE VIZCACHA.

- THE DYING HUANACO.

- THE STRANGE INSTINCTS OF CATTLE.

- HORSE AND MAN.

- SEEN AND LOST,