![]()

PART I

CLINICAL TRIALS

![]()

1.

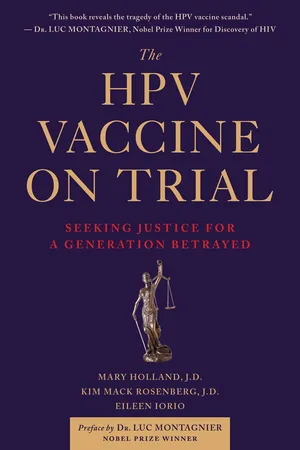

REWARDING THE INVENTORS

In September 2017, luminaries in the healthcare field gathered at the New York Plaza Hotel to celebrate an extraordinary achievement: a vaccine to prevent cancer. Two scientists at the National Institutes of Health had created the human papillomavirus, or HPV vaccine. By 2017, it had been on the market just over ten years, although scientists had been working on it for decades. The Lasker Foundation gives awards to key leaders in the medical field.

At the ceremony, Drs. Douglas R. Lowy and John T. Schiller received Lasker Awards for their groundbreaking innovation. The Foundation celebrates scientists, clinicians, and public servants for advances in research and health. Albert and Mary Lasker, the Foundation’s namesakes, created the Awards in 1945, drawing on Albert’s advertising fortune, which he amassed through selling cigarettes and other products. These prestigious awards, sometimes called “American Nobel” prizes, carry not just acclaim, but $250,000 for each winner.

Drs. Lowy and Schiller, cancer biologists at the National Cancer Institute, had attained a dream—a vaccine to prevent cervical cancer, a killer for women, particularly in the developing world. In 1950, cervical cancer had also been the Lasker Foundation’s theme: Dr. George Papanicolaou won a prize for his Pap test, which could identify abnormal cervical cell growth. Pap tests have saved countless lives over the past 70 years. But Drs. Lowy and Schiller’s work promised something even better: to prevent cancer in the first place. This is what the Lasker Foundation sought to honor.

Dr. Craig Thompson, head of the world-renowned Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, presided at the gala. He called the HPV clinical trials “stunningly successful.” Because of Lowy and Schiller’s pioneering work, the FDA approved the HPV vaccine for females in 2006 and for males in 2011. By 2015, nearly 60 million people around the globe, mostly children, had received at least one dose. Dr. Thompson proclaimed that HPV vaccines had already prevented 400,000 cases of cervical cancer.1 A Lasker Award video went further, saying that over the next 50–60 years, the vaccine would prevent 19 million cases of cervical cancer and 10 million deaths: “The HPV vaccine is like an immunological grand slam. It prevents most cervical cancer as well as other HPV-linked cancers.”2

In his acceptance remarks, Dr. Lowy acknowledged that he and Dr. Schiller would not have been able to develop the vaccine without public investment. For the pharmaceutical industry, the incentives to prevent disease are not as great as those to treat it. Publically financed NIH research had been essential. He also thanked the key manufacturers, Merck and GlaxoSmithKline, for taking big risks. The vaccines have “exceeded even our most optimistic expectations, while also highlighting the value of public-private partnerships in health and disease. Amazingly, eliminating cervical cancer and other HPV-associated cancers as a major public health problem is now a realistic goal.”3

The HPV vaccine sounded miraculous, promising to safely prevent cancer with only a few shots. It sounded almost too good to be true.

![]()

2.

INJURED IN THE TRIALS: TESTIMONY FROM DENMARK

“I didn’t want it to be the vaccine.” Kesia Lyng, Denmark

In December 2017, the online magazine Slate published “What the Gardasil Testing May Have Missed.” With its publication, the article sparked renewed debate over HPV vaccine clinical trials.1 The story focused on Kesia Lyng, a young Danish woman who participated in one of Merck’s Gardasil trials in 2002.2 The article’s description of the clinical trials surprised many but brought a sense of relief to other young people who, like Kesia, had experienced ill health after the vaccine. They could recognize their experience in hers.

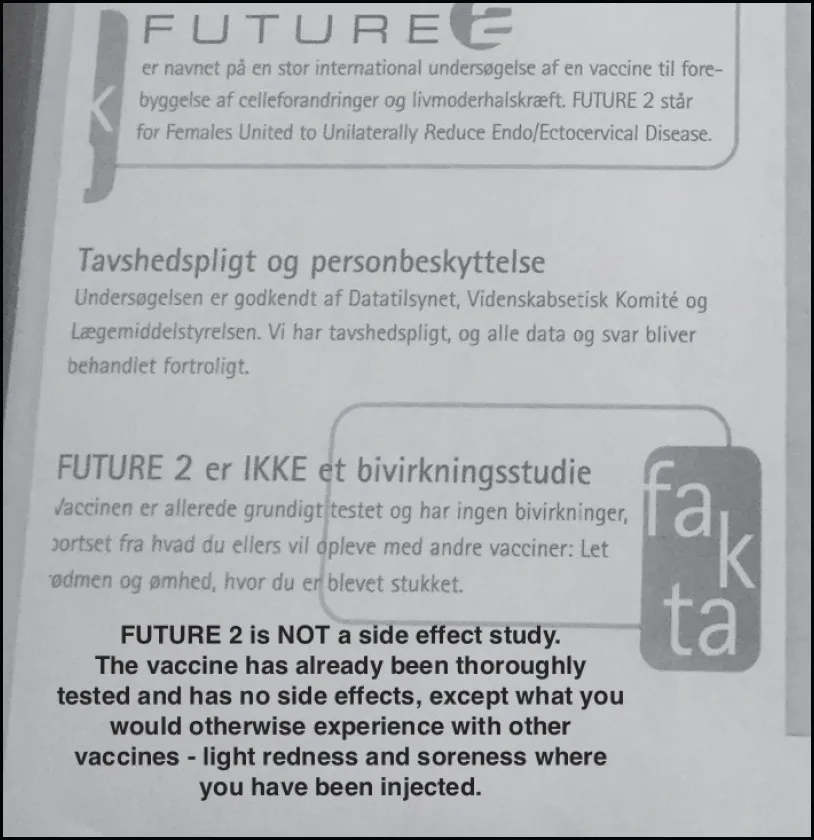

When she was eighteen and still in high school, Kesia received a brochure in the mail about an exciting clinical trial for a vaccine that would prevent cervical cancer. She didn’t know it was possible to vaccinate against cancer. She had heard that getting regular Pap tests was the best way to prevent cancer because most problems could be caught early and treated. The brochure said that the vaccine had no side effects, as it had already been thoroughly tested. It read, “FUTURE 2 er IKKE et bivirkningsstudie,” which translates to “the FUTURE 2 study is NOT a side effect study” (original emphasis on “NOT”). This piqued her interest, particularly because the vaccine had already been proven safe.

Only six months before Kesia received this brochure, her grandmother had died at 68 of cervical cancer. Kesia adored her grandmother; she was Kesia’s world. Her grandmother was the glue that held the family together. Kesia has the fondest memories of her entire family celebrating holidays in her grandmother’s home. She missed her terribly. She wanted to do something, and getting the brochure seemed serendipitous.

The brochure said that half the clinical trial subjects would receive the vaccine and half would receive saline, which seemed like standard practice. When she inquired further, she found out that the clinical trials would take place at her local hospital in Hvidovre, just outside Copenhagen. It seemed like an easy way to do something positive and help the fight against cervical cancer. She signed up.

Source: Excerpt from “Future 2” study recruitment brochure sent to all female 18–23 year-olds in Denmark, 2002.3

Kesia’s parents were skeptical, although they appreciated her desire to do something constructive. They didn’t want her to take unnecessary risks. They discouraged her from participating in the trials, but Kesia was resolute. She was proud to take part so that she could help others avert a similar, painful loss. She had never heard of HPV before the study, but it sounded like a breakthrough. She learned that the study name, FUTURE 2, stood for “Females United To Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease.” She couldn’t wait to get started. And not least, she would earn around $500. That was a lot of money for an 18-year-old!

THE TRIAL BEGINS

Kesia enlisted in Study Protocol 015, a clinical trial, and received her first shot in September 2002. At this appointment, the clinicians examined her and took blood and urine samples. They told her she would either get the 3-shot Gardasil vaccine series, or three shots of saline placebo, which would have no effect. Since the study was double-blind, neither she nor the investigators would know which shots she got until the trial was over. Kesia was nervous. Part of her wanted to get the saline placebo, but part wanted to get the vaccine so that she would be protected against HPV. The nurse reassured her that if she did get the vaccine, it was perfectly safe; her mind was put at ease.

The first injection really hurt. Later that day, she felt tired, and her arm was weak. She was overcome by an unusual feeling all over her body; not dizzy, but strange, and disconnected. She had a weird sensation in her arm for weeks after the shot. But, in the end, she rationalized that she was doing something that might one day help women all over the world. She thought it was just a normal vaccine reaction.

Two months later, Kesia returned for her second shot. It was at this visit that she talked more with the clinicians. They asked her how things went after the first injection. The nurse read from a checklist of possible symptoms related to the injection site and other minor symptoms. Kesia hadn’t received any information from the clinical staff when she received her first shot on how to record unusual reactions; they did not ask her to keep track. She didn’t keep a journal and couldn’t quite remember every ache or pain she had had the previous month. She was told that headaches and fevers were normal, so she took the second shot without hesitation. It was more painful than the first, but she put it out of mind. She had the same reaction as before—she was very tired, and her arm was weak. Her body felt very strange, but those feelings gradually subsided.

Shortly after this second appointment, though, Kesia developed flu-like symptoms, muscle pains, and a strange headache. At times, Kesia felt like her head was in a vice. She began having trouble sleeping for the first time in her life. She felt exhausted, but it would take hours to fall asleep, and she rarely stayed asleep for long, waking every hour. She tried everything, but nothing helped. Lack of sleep was the worst part of Kesia’s illness. It was so stressful and upsetting to be this exhausted and not able to find relief. Kesia didn’t realize it, but this was to be her new nightly experience for the next fourteen years.

Kesia’s flu-like symptoms and sleep problems persisted that winter. There was no requirement for her to report back to the hospital. She missed a lot of school because of fatigue and constant pain but tried to catch up. She had to retake a few exams. A...