![]()

1.

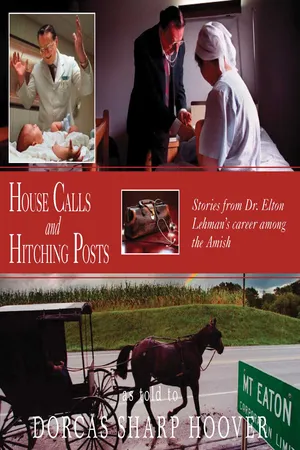

THE SCENT OF TROUBLE

With a puzzled look on her youthful face, the receptionist studied the young man entering the office. It wasn’t his straw hat or suspenders that held the stares of the secretary and patients in the waiting room. It was the rusty coffee can concealing the newcomer’s hand. A pungent odor filled the room, and the Amish patients eyed each other knowingly. Kerosene. The scent of trouble.

Another emergency, the receptionist thought, studying the conspicuous can as she answered the ringing phone. “Mount Eaton Clinic, Dr. Lehman’s office.” Nancy brushed back strands of brown hair escaping the barrettes that secured her hair into a bun. Her eyes kept returning to the hand held into the kerosene-filled can.

“So, you would like Dr. Lehman to stop by your house tonight to check the traction on your daughter’s broken leg?” Nancy asked, eying the coffee can. “Can you hold, please, while I check with the doctor?” A moment later Nancy confirmed the house call.

Right again, Rebecca, she thought, replacing the telephone receiver as the young Amishman set the can on the counter in front of her. You always said Mount Eaton Clinic is like the community emergency room here in the north end of Amish Country, and you’re right again. One never can tell what emergency will burst through those doors!

“Let’s see your hand,” Nancy gripped her pen and leaned expectantly toward the can.

The youth lifted a mutilated hand from the container, revealing white circles of naked bone and red, tattered tissue where fingers should have been. Nancy froze in horror as the patient fished dripping, dismembered fingers from the can. “Put them back! Put them back!” she recoiled in horror.

“Ach mei zeit!” the patients in the waiting room chorused. “Ei yi yi!”

“I should have known better,” the receptionist muttered while nearly colliding with a nurse in the hall. “Alice! Get Doc! We’ve got an emergency!”

No one in the paneled waiting room spoke. The Farm and Ranch, Sugarcreek Budget, and Guideposts lay ignored in patients’ laps as every eye followed the young man with his odorous can until the door shut behind him.1

After a long moment, a lanky patient seated in the corner thoughtfully rubbed his smooth-shaven chin. “Poor guy’s wasting his time here. The doctor will send a case like that straight to the emergency room. He should have gone there directly,” the man sniffed. “No doctor would treat a hand like that in the office.”

“Then you don’t know Doc Lehman,” said a balding patriarch stroking his long, gray beard. He set his gold-rimmed glasses higher on the bridge of his nose and appraised the outspoken man in the corner. Obviously, this Englischer was a newcomer to the area.

“Let me tell you something,” the elderly man proposed quietly, leaning forward on his cane. “Dr. Lehman goes out of his way to accommodate patients like us Amish folk who don’t have insurance to pay hospital bills nor cars to take us to the emergency room. Why, some time back, I had a cyst almost as big as an egg and Doc cut it out here at the office.”

“We’re talking about surgery,” the Englischer persisted impatiently. “I’ve never known a general practitioner yet who’d do that type of extensive repair right in the office. That’s a job for a surgeon in an emergency room.”

“Well then Lehman ain’t no general practitioner,” quipped a plump, graying woman tugging at her bonnet ties. “I don’t know what kind of doctor he is, but we call him a country doctor. Why, my Lester got his hand chewed up in a corn picker, and Doc sewed him up again just as nice and neat as you please.”

“Yah, that’s Doc, all right,” a young woman shyly agreed as she patted a sleeping infant lying on her lap. She carefully smoothed the wrinkles in the apron that nearly brushed her black shoestrings. “Our neighbor got her hand all chopped up in a steak cuber. Doc fixed her hand up real nice. Put 96 stitches in it. He worked on it three hours and now you’d hardly know it was ever hurt.”

“Ninety-six stitches!” the man in the corner whistled. “Here in this building? I never heard of a doctor caring for those kinds of emergencies in the office. I’ll believe it when I see it.”

Still weak from seeing the dismembered fingers, Nancy couldn’t help but smile at the patients’ conversation. They talked as though their doctor could repair any injury they’d encounter. No matter how severely mangled, they expected their “Doc” could sew them up and send them on their way again. Nancy recalled a few emergencies that Dr. Lehman needed to transfer to the hospital: the child whose throat was slit in a dog attack, the young hunter who accidentally shot himself in the abdomen, and the man with the chainsaw wound on his head.

Back in one of the four treatment rooms, Alice offered a chair to the youth with his hand in the coffee can and observed him closely for signs of fainting. A moment later, Dr. Lehman swept into the room.

“What do we have here?” he asked, adjusting his glasses and gently lifting the mutilated hand from the can.

“Ach yammah. I ran it through the saw at the mill. Too schuslich, I guess,” the patient answered, studying Dr. Lehman’s dark hair, ruddy cheeks, and solid build.

“Well, one has to look at the bright side,” the doctor replied with the trace of a smile. “From now on it won’t take as long to trim your fingernails!”

“Ha! Never thought about that!” Joe chuckled. “That just shows that there’s something good in everything that happens.”

While Dr. Lehman assessed the damage, Rebecca carefully arranged a syringe, forceps, bone-snips, suture driver, and a stack of gauze on a sterile towel next to a bottle of Zephrin. She set a waste can on the floor beneath the end of the examining table.

First of all, he needs something for pain, Dr. Lehman thought, examining the wound. “Tylenol with codeine, Rebecca,” he instructed, noting the patient’s restrained emotion so characteristic of the Amish folk.

“So I see you brought the fingers with you,” the doctor observed, examining the contents of the coffee can. “Do you want them reattached?”

“You mean you could sew them on again?”

“I don’t have the facilities to do that here to give you proper use of your fingers again. You’ll have to go to the hospital if you want them reattached, but it could be done.”

The patient shook his head. “Ach, that could cost me an arm and a leg. That would be dummheit, giving an arm and a leg to fix a couple of fingers!”

“In that case,” Dr. Lehman replied, “I’ll have to trim your bone back to the next joint. That will give us a flap of skin to bring up over the exposed end of the finger, and then I’ll stitch it up. I can do that here, but you’ll have to understand it is not the most pleasant procedure.”

“Yah, that’s okay. Just go for it.”

While Joe soaked his hand in Dreft laundry detergent to disinfect the mutilated fingers, the doctor and nurses quickly tended to several other patients. The doctor extracted a kernel of corn from a youngster’s ear and examined a toddler scheduled for a measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine. The child lay quietly on the examining table, her large eyes watching the doctor hold the stethoscope to her chest. “She’s growing nicely,” he observed. “It doesn’t seem that long since I delivered her.”

“I know it,” the mother agreed, stroking the toddler’s hand reassuringly. “They grow so fast. I just want to treasure every day.”

I couldn’t ask for more ideal patients, Dr. Lehman thought. Such pleasant, respectful folks. He never imagined that this child would die half a dozen years later when a car plowed into a group of 10 Amish children walking home from a birthday party. The accident would draw national media attention.

Out front at the receptionist’s desk, Nancy slid open the window partitioning her cubicle from the waiting room. “Doc will be busy with the emergency for an hour or so,” she announced. “If any of you want to reschedule your appointment, I’ll be glad to work you in at a later date. But for those who want to wait, Dr. Lehman will see you over his lunch hour.”

A few rescheduled their appointments while others chose to sit and chat. The patients accepted these kinds of delays as part of a country practice, and they were glad Dr. Lehman was willing to treat their emergencies.

“What about you, Mr. Keener, do you want to set up a new appointment?” the receptionist asked the lean, clean-shaven stranger.

“No, I’ll wait.”

“You could run over to the restaurant and pick up a sandwich in the meantime, if you want,” she suggested.

Mr. Keener gazed thoughtfully out the window at the horses standing patiently at the hitching post across the road. Then he turned back to the waiting receptionist. “No thanks. I want to be here when that guy comes out so I can see for myself if the doctor treats such a case.”

“Does Doc have any openings tomorrow?” a middle-aged woman asked.

“The doctor’s not in on Thursday. Is Friday at 2:15 okay?”

“That’s fine, but what does Doc do on his day off, anyhow? Go fishing?”

“Oh no. He goes over to Country Lawn Nursing Home and makes rounds, checking on the residents there at Navarre.”

“Hmm. Always busy helping others. Well, it’s good that man didn’t cut off his fingers tomorrow when Doc’s not around.”

“That’s for sure. But I suppose something will happen tomorrow, too. It seems the worst cases turn up when the doctor’s out.”

“Ach my! Surely not worse than this case today?”

“Oh yes,” Nancy relayed casually as she addressed an envelope. “We had a man bring in his little boy who was blue-looking. He found the little fellow in a water trough.” The ringing phone cut Nancy short, so she handed the patient the appointment reminder card and reached for the telephone.

Down the hall, Joe’s nostrils tingled with the clean scent of the Dreft bubbles bursting as water swirled around his throbbing fingers. “Don’t know why I need to soak them in this soapy water,” the boy muttered. “Why, the kerosene killed all the germs.”

His eyes swept the room while he waited. He took in the brown-paneled walls, high window, metal cabinet, jar of wooden tongue depressors, gauze pads, small sink, and large goose-necked lamp at the end of the examining table. An Enfamil calendar hung on the wall along with a Norman Rockwell painting of a portly doctor placing his stethoscope on the chest of a young patient’s doll.

The door opened and Dr. Lehman strode purposefully into the room. “Okay, Joe,” he said, lifting the dismembered hand from the Dreft solution. “Let’s take another look.” The doctor silently studied the finger stubs for a moment then gently poured Zephrin over them. He brushed specks of sawdust, grease, and dirt from the tissue and laid the hand on a sterile towel.

“This will sting a little,” the doctor warned. He took the syringe the nurse handed him and jabbed the needle into the base of an injured finger. “And another little sting,” he said injecting the needle into another side of the finger.

“Can you feel this?” Dr. Lehman asked, tapping the forceps against the finger.

“Can’t feel a thing.”

“What about this,” Dr. Lehman asked, snipping at a bit of tissue.

“Nothing.”

“Let me know if you feel any pain,” Dr. Lehman said as he began dissecting the tissue, muscle, and tendon from the skin and bone. The doctor snipped painstakingly around a finger until only a hollow sleeve of skin remained over the bone above the joint. Gently, he rolled the sleeve of skin well below the knuckle. In gloved hands, he picked up the bone-snips—a tool resembling a pair of pliers with sharp, broad blades similar to a small hedge trimmer. He straightened his shoulders and inhaled deeply. Carefully, he aligned the snips, clamped the handles together, and a piece of bone plopped onto the towel.

Dr. Lehman dissected remaining bits of tissue from the sleeve of skin and crafted a flap to cover the bleeding stump. After dousing the finger with more Zephrin, the nurse draped a sterile towel over the hand to keep the suture clean. Only a stub of the index finger poked through a hole in the towel. Dr. Lehman folded the flap of skin he had meticulously scraped and shaped over the naked bone stub, and prepared to stitch the flap in place.

Joe watched intently as Dr. Lehman clamped a suture holder onto the end of a curved needle. The doctor pierced through one skin layer and the adjacent tissue. Then he released the suture holder, fastened the instrument to the pointed end of the needle protruding from the skin, and ...