![]()

1.

What is the difference between the Amish and the Mennonites?

Anyone who tries to answer this question in one simple sentence is either naive or purposefully unkind.

Which of us would want our lives summed up in one sweeping statement? Yet many of us demand this of other people’s lives.

The danger of generalizations

As authors, we must declare ourselves on the very first pages of this book. It is impossible to interpret the lives of a people—any people—in one or two quick sentences. It seems a violent act.

When a people become the object of curiosity and tourism as the Amish and the Mennonites have in various parts of North America, a lot of shallow, fast-buck, one-line interpretations appear.

There are dozens of varieties among the Amish and Mennonite groups around the world. Words like “always” and “never” seldom apply in describing the whole Mennonite-Amish family. On most of the topics we will cover in this book, there are many shades of belief and practice among our various groups.

There are dozens of Amish and Mennonite groups around the world, each with specific practices and beliefs. It is impossible to summarize these peoples’ lives in one short sentence.

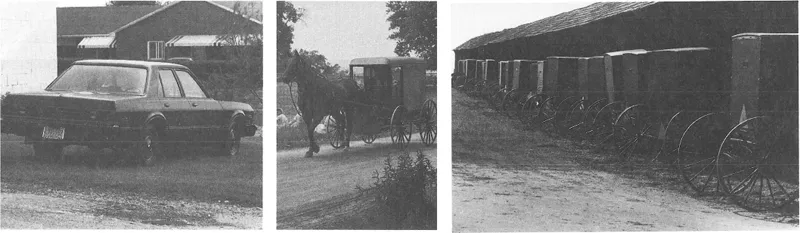

One issue which many of the groups approach differently is transportation. Old Order Amish buggies (center) in Lancaster County have grey tops. But Amish buggies vary in other communities across North America, both in shape and color. Some groups who drive cars illustrate separation from worldliness by painting the chrome on their cars black (left photo). The photo on the right pictures a row of Old Order Mennonite buggies which have black tops.

Our purpose is to qualify generalizations while being as specific as possible. This can be frustrating. We will use the words “most” and “some” and “seldom” a great deal. Many readers will wish we would make more sweeping observations. But one-line generalizations create human zoos. People become spectacles.

The various Amish and Mennonite groups of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania are the central focus of our study. We will attempt throughout the book, however, to include information about the worldwide peoplehood.

In general

We will risk several generalizations at this point:

1. Most Mennonite and Amish groups have common historical roots. Their beginnings (1525) date from a group of persecuted radical Christians nicknamed “Anabaptists” at the time of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. They sought a return to the simplicity of faith and practice as seen in the early Christian church in the Bible. The Amish division took place a century and a half later in 1693. This history will be discussed in detail in the next chapter.

2. All Amish and Mennonite groups are Christian fellowships. Most of them stress that belief must result in practice. “By their fruits you shall know them” (Matthew 7:20). Therefore, emphases on lifestyle and peace have distinguished most of the groups throughout the centuries. More on this in Chapter 3.

3. The differences among the various Amish and Mennonite groups through the years have almost always been ones of practice rather than basic Christian doctrine. This is not to minimize the differences, because they are real. But even today a survey of the whole family would show few differences on the Christian teaching of creation and redemption and a great many on how one should dress and how a congregation should make decisions.

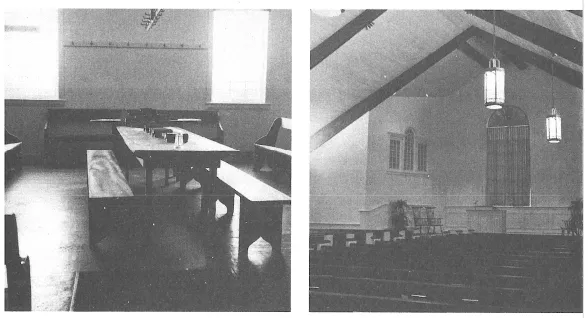

Some groups such as the Old Order Amish and urban house fellowships worship in homes. Those who worship in churches vary from the simple three-quarter-round meetinghouse of the Old Order Mennonites to the more Protestant look of modem Mennonite sanctuaries.

More specifically

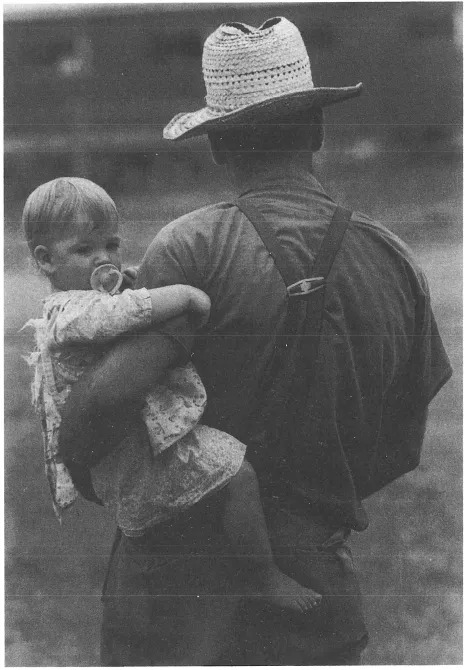

Amish groups tend to be more cautious on technology and involvement with the larger world than most Mennonites. Most Old Order Amish, for instance, drive horse-drawn carriages, dress “plain,” refrain from the use of electricity, emphasize occupations close to the farm and the home, and forbid higher education. Many Mennonites, on the other hand, are considerably more acculturated. They embrace education and technology as opportunities, accept reluctantly the stress which modern life places on marriage and the family, and encourage an enlargement of the fellowship through worldwide missionary activities.

But this is very general. Thousands of Mennonites drive horses and buggies, avoid higher education, and are cautious on missions. And some Amish groups drive cars and encourage high school and mission work.

We find it more helpful for purposes of discussion to collect the many groups into two main categories: 1) those who take their cues for decision-making primarily from their faith fellowship, whom we shall refer to as “Old Order” (this may include many small urban groups who are “Old Order” in their dynamic); and 2) those who are more influenced in their primary decision-making by what the larger society thinks than by what their faith fellowship believes, whom we shall refer to as “modern.”

These categories of “Old Order” and “modern” are much more helpful than “Mennonite” and “Amish” in describing the total family. In many cases, the Old Order Amish, the Old Order Mennonites, the Old Colony Mennonites, the Hutterites, and an inner-city Mennonite house church may share more in common than they do with more rapidly acculturating Mennonite and Amish groups.

In summary

One last comment. There are more similarities among the Mennonite-Amish fellowship worldwide than there are dissimilarities.

Obviously there are many differences, especially among the groups at the far edges of the spectrum. But there remain many unifying themes among the various Mennonite and Amish groups worldwide, even though the groups are organizationally independent.

The remainder of this book will explore both the differences and the likenesses of our peoples.

![]()

2.

When and how did these people get started?

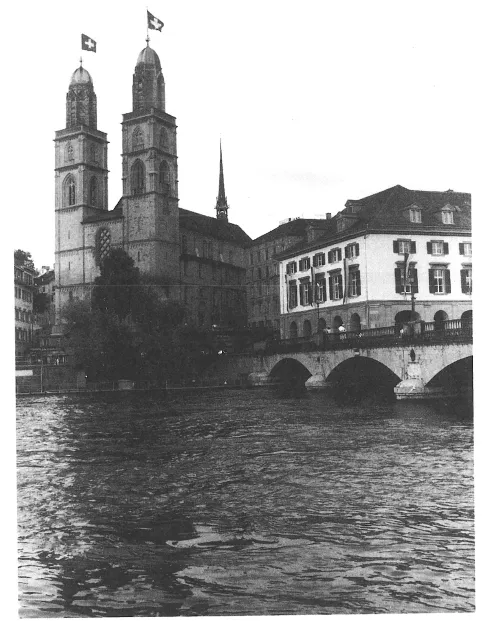

All Amish and Mennonite groups trace their spiritual heritage back to the time of Christ and the early Christian church. The specific movement from which these groups descend, however, began on January 21, 1525 in Zurich, Switzerland.

The Anabaptists

When the Protestant Reformation broke open the religious world of sixteenth-century Europe, Martin Luther led the challenge against the Roman Church. At the same time, a Reformer named Ulrich Zwingli emerged in Zurich. Both men advocated a new Christian order. They preached the Bible in the language of the peasants and proclaimed that the grace of God and forgiveness of sins were available freely to all by faith alone. It was a time of great turmoil.

In the midst of this religious and social upheaval, a group who called themselves Brethren formed a fellowship. They were nicknamed Anabaptists (which means “rebaptizers”). They became severely persecuted by both the church of Rome and the Reformers. Why? Because they represented a third option: a belief that the church should be a group of voluntary adults, baptized upon confession of faith, and like the early Christian church, separated from the world and the state.

It began when several young radical students of Zwingli’s became disappointed when he pulled back from his earlier stand against baptizing infants. The Reformers were turning their attention to reorganizing society after the religious upheaval; the Anabaptists, led by Conrad Grebel, Georg Blaurock, and Felix Manz, sought a pure church, free from state control (a new and radical idea in those days), open to adult believers from any region.

The Anabaptist movement began in 1525 in Zurich, Switzerland at the time of the Protestant Reformation among several of Ulrich Zwingli’s students. Zwingli preached at the Grossmunsterf pictured above.

The movement spread quickly and the Anabaptists were put to death by the thousands; many of the leaders were dead within a few years. This severe persecution often forced the Anabaptists to meet at night. Worship was held secretly, sometimes in caves in the mountains. Leaders travelled illegally, often evading officials to stay alive. This persecution led many to an attitude of withdrawal from the larger society (an attitude still shared by many descendants of the movement today).

The Mennonites

The Anabaptists were not a leaderless group. But they stressed the priesthood of all believers, and because so many of the able leaders were martyred so rapidly, no one leader emerged. This tradition continues today among the descendant groups.

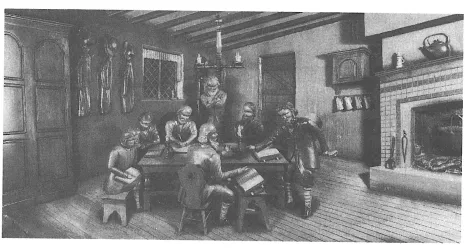

This painting by Amish folk artist Aaron Zook depicts the controversy between Mennonite elders Jacob Amman (standing, right) and Hans Reist which led to the beginning of the Amish church in 1693.

Perhaps the best known leader was Menno Simons, a Catholic priest from The Netherlands, who joined the movement in 1536. His moderate leadership and prolific writings did so much to unify the scattered Anabaptists that they soon were nicknamed “Mennonites.” But Menno shared the leadership with many others.

Today there are Mennonites of many races and tongues in fifty-some countries around the world. Many descend from early beginnings in Switzerland, Germany, and The Netherlands. Many joined the fellowship through mission work. Others sought affiliation at their own initiative.

The Amish

If one believes that the church consists of adults who voluntarily commit themselves to the fellowship and discipline of their fellow believers, then the purity of the church becomes very important.

In 1693, a young Swiss Mennonite elder who felt the church was losing its purity broke with his brethren and formed a new Christian fellowship. His name was Jacob Amman and his followers were nicknamed “Amish.” The debate: if a member is excommunicated from the fellowship (the “ban”), how severe should the censure be? Several attempts to heal the division failed.

The Mennonites and the Amish have split many times. Almost always the concern has involved the purity and faithfulness of the fellowship. Personality conflicts have also contributed.

Most Amish groups today consider themselves conservative cousins of the Mennonites. The Old Order Amish live mainly in the United States (22 different states), but some communities are found in the Canadian province of Ontario.

![]()

3.

Are they a Chris...