eBook - ePub

Ecology, Ethics, and Interdependence

The Dalai Lama in Conversation with Leading Thinkers on Climate Change

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ecology, Ethics, and Interdependence

The Dalai Lama in Conversation with Leading Thinkers on Climate Change

About this book

Powerful conversations between His Holiness the Dalai Lama and leading scientists on the most pressing issue of our time. Engage with leading scientists, academics, ethicists, and activists, as well as His Holiness the Dalai Lama and His Holiness the Karmapa, who gathered in Dharamsala, India, for the twenty-third Mind and Life conference to discuss arguably the most urgent questions facing humanity today:

- What is happening to our planet?

- What can we do about it?

- How do we balance the concerns of people against the rights of animals and against the needs of an ecosystem?

- What is the most skillful way to enact change?

- And how do we fight on, even when our efforts seem to bear no fruit?

Inspiring, edifying, and transformative, this should be required reading for any citizen of the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ecology, Ethics, and Interdependence by Dunne D. John, Daniel Goleman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Ecology, Ethics, and Interdependence

Daniel Goleman

HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA: In order to explore ethics, we must first depend on research for facts about reality. We can rely on scientific methods to uncover reality with no concept of right or wrong, no positive or negative. Then, after finding the unbiased facts, the next questions we can ask are “What are the implications?” and “What is the value?” So I think we must first approach these issues with research, simply trying to find out reality. Even phenomena such as anger, fear, suspicion, and distrust should be investigated without bias. We should investigate without considering anger as bad or compassion as good, but simply with the aim of discovering reality and its causes and effects. Then we can consider the ethical implications for our well-being.

When considering ecology, I think that — in combination with science, interdependence, and philosophical view — ecology offers a way to explain reality. Things exist due to many factors. That’s the basic concept of interdependence. As with research, with interdependence there are no notions of good or bad, just reality.

So for the next few days our discussion will be serious, and eventually we can share our ideas with others who have similar interests in this field. It is our responsibility to create more interest and awareness in other people’s minds.

So let’s talk about ethics. Everybody agrees that there are a lot of problems on the planet. Every morning when I listen to BBC, I hear about some problem, some killing here or there. Recently I heard about unrest in England and I was really shocked. I was shocked and surprised, you see, because I had the impression that the British had become very mature. On several occasions when I visited England, I hardly saw any police. I had the impression that English people were generally self-disciplined. So when I heard about this unrest in England, I was very surprised.

And just this morning I heard on a BBC broadcast about flood victims in Pakistan and the fact that the aid workers trying to help these people are about to run out of funds to continue their help. Very sad, isn’t it?

If we investigate why such things happen, of course there are natural disasters beyond our control. But we could also prepare better, care for people better, and create an overall higher standard of living. And this, I think, can help reduce suffering.

Another point is that corruption contributes to these problems and makes them worse than they already are. Corruption is creating serious consequences in Africa and in many areas. In a way, corruption is like a disease, like a cancer for the whole planet, for humanity.

What is wrong? This corruption is not due to the lack of a judicial system, or the lack of police forces, or the lack of government organizations; ultimately, it is due to a lack of ethics. It is due to a lack of self-discipline, for self-discipline is entirely based on ethics. We have the responsibility to bring awareness to the fact that the many problems we are facing ultimately result from the lack of inner discipline, of moral ethics.

And while the primary way to promote moral ethics is through religion, many religions, including Buddhism, have had opportunities over the last thousand years or so to promote ethics — and have often failed. So now we must find new ways and means to create conviction in others that behaving ethically is in our own best interest and for our own well-being. That’s the main goal.

We have moral responsibility to create this awareness in more people, and in this way, I really appreciate the efforts of all the participants, particularly the scientists.

I think Richard Davidson, for example, has made such a great contribution with such motivation that I feel that I want to not only acknowledge you, Richie, but also repay your kindness. And you remain humble. That’s very good. That I like. If a good scientist becomes too proud, he may lose respect. The same is true with religious leaders.

DANIEL GOLEMAN: This is a quite an unusual forum. Here we have an integrative, collaborative dialogue between science, spiritual traditions, and the humanities. We are going to use these multiple perspectives to address the current environmental crisis. This is a very unusual topic for Mind and Life.

Out of twenty-three meetings, I think this is only the second to address the “life” side of Mind and Life. As you will hear from the scientists, there is sad and bad news, and also some very hopeful news. But at the beginning we are going to make the scientific case that, as a species, we are engaged in what amounts to a slow-motion suicide if we continue the way we are now. It’s because of this urgency, and the moral importance of the situation, that we felt this was a compelling topic for a Mind and Life meeting.

Your Holiness, in your talks, you often cite the love of a mother for her child as a basis for compassion. Today, we’re facing a real paradox: even though we love our children as much as anyone in human history has, every day, each of us unwittingly acts in ways that create a future for this planet and for our own children, and their children, that will be much worse. The problem is rooted in a very important term that we are going to hear this morning: the Anthropocene age. So what does Anthropocene mean?

Diana Liverman will go into that in more detail later, but for a basic understanding, consider that geological history extends over millions of years, and that in the last few hundred years we’ve entered into a unique time in history. This is the first time the actions of one species are altering the planetary systems that support life in a negative way. That’s the slow-motion suicide. And we are confronted with the dilemma that we have an urgent, compelling need to save ourselves from our worst enemy: ourselves.

The problem from an evolutionary psychology point of view is this: Our brains were formed over several hundred thousand years, and the alarm system in the brain, the system that recognizes threat and danger, was designed for detecting snarling tigers, not for detecting the very subtle causes of this planetary degradation. Our sensory system does not actually register the danger. It’s too big, or it’s too small, and therefore it’s invisible to us. Our amygdala and its brain circuitry — the alarm system of the brain — doesn’t realize there’s a danger and doesn’t activate.

This makes it very hard to motivate people to do anything about what is perhaps the worst crisis in human history. Rather, many people go through their daily lives as though nothing were happening. We’re all in a kind of trance. Because of this design flaw in the brain, there’s no sense of immediate threat.

In exploring this, I feel that Buddhism and Christian theology, as well as philosophy and psychology, have very important perspectives to offer science. Science documents what’s happening, but it doesn’t necessarily have within it the mechanisms to mobilize people to act in a skillful way. And that’s the particular aspect of reality, or truth, we’re seeking to explore over the course of the week.

2 The Science of Climate Change

PRESENTER: Diana Liverman, University of Arizona

DANIEL GOLEMAN: Diana Liverman is an environmental scientist, formerly at the University of Oxford and now at the University of Arizona, where she directs the Institute of the Environment and is a professor of geography and development. She looks at how environmental changes are affecting the developing world, and she has written many books and scholarly articles on the subject. She’s a coauthor of the article “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity” (Nature, 2009), a paper that details how human activity is driving the degradation of the handful of planetary systems that support life. While we often hear about and talk about global warming, it is actually only one dimension of eight or nine world systems that support life.

DIANA LIVERMAN: Humans are changing the global environment and transforming the planet in many ways that affect the potential for our survival and the survival of other species. I represent an international group of scientists who are working very hard to try to understand what’s happening to the earth, to the earth’s systems, and how humans are changing these systems for better or for worse.

I want to set the scene for the conversations this week by showing how the rate of human impact on the planet has been accelerating over the last sixty years in a new era that we are calling the Anthropocene age. I’m going to make the case that these changes are not just affecting climate but also creating multiple risks to life: threats to water supplies and to ecosystems, increased pollution, and overuse of resources.

I will then discuss “planetary boundaries,” which is the idea of setting limits that could guide the way we use the planet. In this context, I will discuss a set of environmental thresholds that we want to avoid.

I’ll end with an update on the latest findings about climate change, and particularly some results about the Himalayan region. In the past five years, since the last big study on climate change was done by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), we have new scientific results that give us even greater concern.

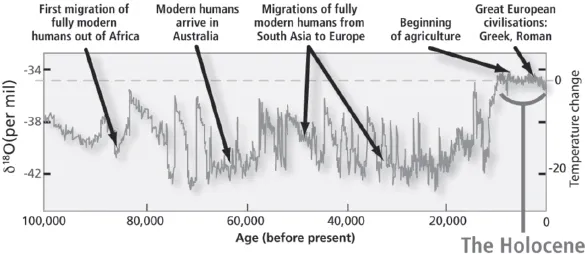

A Look at Human History

DIANA LIVERMAN: Figure 1 is based on chemical data from ice cores that show how the earth’s average temperature has changed over the last 100,000 years. What you can see here is that 100,000 years ago, the earth was much cooler than it is today. The average temperature of the earth, from a few thousand years ago to as recently as 1950, was about 13.5 degrees Celsius.

HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA: As I understand it, some parts of the world today, such as Siberia, are very cold, but there are indications, based on archaeological findings, that at one time it was a very hot plateau. Similarly, was not India once under the sea? Are these changes within the time frame you are showing us?

DIANA LIVERMAN: Not really. The changes you are talking about took place over millions of years. What we are talking about includes two relatively recent geologic periods within the past 100,000 years: the ice ages and our current climate and weather patterns.

If we look at the graph (figure 1), at the left is the oldest period, starting a period of 90,000 years when it was quite cold. This was the period of the last ice age, the Wisconsin glaciation that ended around 12,000 years ago. There were very few humans during this period, and they migrated around the earth in small groups. They were living from hunting, gathering plants, and fishing.

Figure 1. 100,000 years of human history

The next point I want to show is on the right-hand side of the graph. There’s a 10,000-year period where it warmed up to a much more comfortable temperature of just less than 15 degrees Celsius. What’s interesting is that this is the period when agriculture developed. It’s when the great civilizations developed, and many people think of this as an ideal period for human development and for many other species. This period was very good for humanity. It’s the period when our populations grew, when we were able to grow food. This good period is what we call the Holocene.

The reason I wanted to show you this is because this Holocene period was a period of balance for humans and the planet. It was a period when we lived in relative harmony. I’m showing you this to set the stage for what we are doing now, which is taking ourselves out of the Holocene and into a period that could be much more challenging for the planet; for humans and for plants and animals.

So for the last 10,000 years the earth’s systems have been in balance; human activities were moderate, and they did not have global impacts on the planet. Then, about 250 years ago, things changed, particularly with the Industrial Revolution and with advances in medicine that allowed populations to grow.

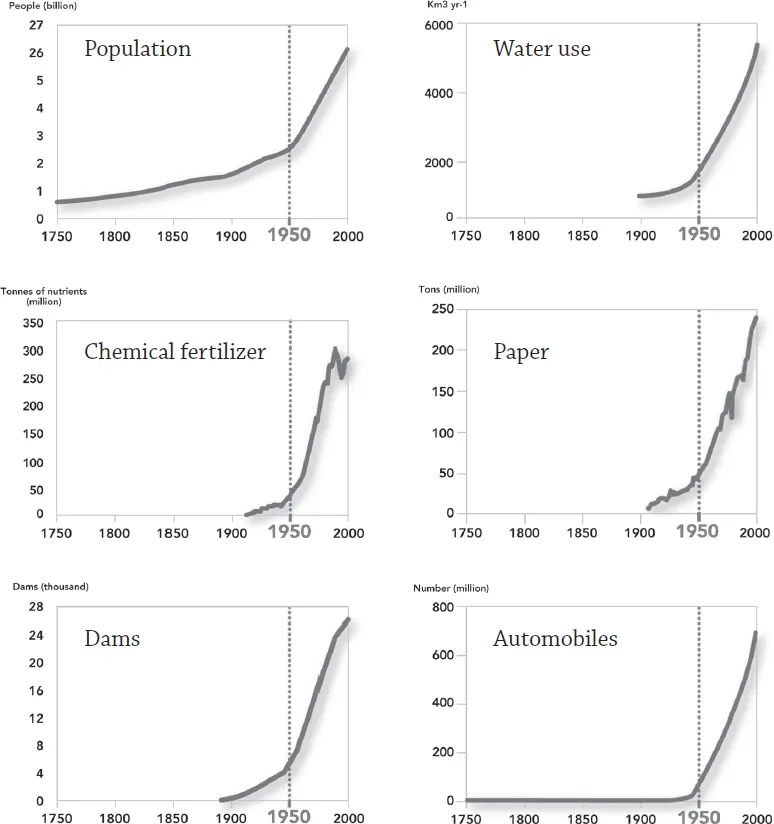

The Great Acceleration

DIANA LIVERMAN: What I’ll do now is talk about the last 250 years. I want to show you a series of graphs that chart human activities and how they’ve grown over this period. Each graph shows growing human activity on the planet. On each of these graphs I’ve put a dotted line at 1950. On almost every graph you can see significant acceleration in growth at about 1950. This is the work of my friend Will Steffen, executive director of the Australian National University Climate Change Institute. He put together a series of graphs, and when we sat down and looked at them, we suddenly realized that there was a real change in the rate of growth at around 1950. We’ve had a “Great Acceleration” in our human impact on the planet.

This Great Acceleration is due to the growth in human population and consequently to the growth in resource use, particularly in the industrialized world. The impact is not only based on the number of people on the planet but more precisely on how much each person consumes, which varies from country to country. We’ll look more closely at this later.

The first graph in figure 2 shows the world population. You can see the rapid growth. But this is actually one graph where we do have some good news. We know now that the population is likely to level off sometime around 2050 at about 9 billion people. It’s one of the few activities where we see, perhaps, some good news.

HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA: Is it the result of family planning, or is it simply naturally occurring?

DIANA LIVERMAN: It’s the result of millions of women around the world choosing to have fewer children.

HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA: Yes, through awareness, through education.

DIANA LIVERMAN: Yes, and it’s often because women have more opportunities. There’s more health care for them and they have been educated. When this happens they can make the choice if they would like to have fewer children.

Figure 2. The Great Acceleration since 1950

This next graph shows the increase in water use. The left-hand side of the graph is blank because we didn’t have any good data on water use until around 1900, but you can see the rapid increase since 1950.

The next graph is the use of chemical fertilizers, not traditional fertilizers. And here again you can see great growth. The change in 1950 is associated with the green revolution, which was the large increase in agricultural production, particularly in places like India. This increase in food production, while fewer...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Publisher’s Acknowledgment

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Ecology, Ethics, and Interdependence

- 2. The Science of Climate Change

- 3. The Ethical Burden of Climate Change

- 4. Footprint to Handprint: The Science of Measuring Impact and Making a Difference

- 5. Ethics and the Environment

- 6. The Uncomfortable Truth: On the Treatment of Animals

- 7. Religion’s Responsibility

- 8. The Dalai Lama Responds

- 9. The Influencers of Choice and Decision Making

- 10. From Motivation to Action: A Buddhist View

- 11. Presence and Action Are Needed

- 12. Environmental Activism: Strategies and Ethics for Today’s World

- 13. Solutions for a Sustainable World

- 14. Appreciation and Thanks

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Image Credits

- Index

- About the Editors

- Copyright