The ILA has many members who are exceptional historians of light therapy, and it is they who initiated me into this aspect of the field—Brian Breiling to be sure, the editor of the pioneering 1996 anthology Light Years Ahead, but also Jacob Liberman, Alexander Wunsch, and Karl Ryberg, whom we speak of later. As they conducted their search, they accumulated a collection of rare documents and ancient books on light, a veritable treasure trove of information and anecdotes on the subject. Much of what follows has been inspired by their words.

Figure 1.1. Dr. Brian Breiling

LIGHT THERAPY IN ANTIQUITY

Few ancient civilizations are without a cult involving the sun, the importance of which is primordial in any hierarchy of gods. The sun is the source of life, abundance, eternity, wisdom, and, of course, light. We find gods of the sun everywhere we look, whether it be ancient Egypt, Babylonia, India, China, Greece, Rome, or the Celtic and Aztec civilizations. In some rare cases very precise facts have come down to us with regard to heliotherapy, practices involving the use of sunlight for medicinal purposes. It is quite likely that the majority of these ancient peoples had similar knowledge.

From Cults of the Sun to Heliotherapy

One of the oldest extant testimonials comes from the Egyptian Old Kingdom and dates from approximately 2600 BCE. It was attributed to the great sage Imhotep, the legendary architect of the Saqqara pyramids, and contains medical formulas that indicate a profound understanding of the effects of light. The importance accorded each moment of the day with regard to the appropriate treatment suggests an understanding of chronobiology, the science of biological rhythms controlled by the cycle of the sun. The use of solar rays for the sterilization and drying of food is also mentioned, together with the photochemical activation of pharmaceutical preparations. Imhotep even practiced a technique known today as photodynamic therapy (discussed in chapter 5) through the application of photo-activated tar and resins.

The ancient Greeks were also fervent practitioners of heliotherapy. In 450 BCE, the great historian Herodotus described the use of solariums, areas of healing based on the light of the sun, stating that “being exposed to the sun is highly recommended for those people who need to regain their health.” Hippocrates of Kos (460–370 BCE), the “Father of Medicine,” insisted on the importance of light and the heat that emanates from it to fortify the bone structure as well as treat a multitude of ills, including rickets, obesity, and diverse metabolic disorders. He would cauterize scabs with the aid of light focused though crystal and quartz, which transmitted the photoactive ultraviolet rays. For the Greeks, the connection between light and health was clear: Asclepius, god of medicine and healing, is none other than the son of Apollo, god of the sun. The Greeks’ cultural successors, the Romans, perpetuated this awareness. Their legal code contained “right to light” clauses guaranteeing people’s access to sunlight in their homes, buildings that frequently featured a solarium. One of the great second-century physicians, Soranus of Ephesus, a Greek who practiced in Rome, recommended exposing jaundiced newborns to the sun, thereby foreshadowing modern neonatal jaundice treatments that use blue light.

Figure 1.2. Apollo, god of light, music, and prophecy (photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen)

From Heliotherapy to Chromotherapy

Another form of light medicine even more specific than heliotherapy is chromotherapy, the therapeutic use of color.

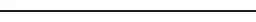

From the very beginning, humankind has demonstrated a great deal of ingenuity with regard to the creation and manipulation of color. Seventeen thousand years ago the artists of the Lascaux Caves knew how to prepare an attractive palette of colored pigments to accomplish their extraordinary work. The Egyptians demonstrated great respect for the power of color, as demonstrated in the very precise and codified iconographic use of various hues that can still be seen in Egyptian bas-reliefs and works on papyrus. Temples and statues were painted in the liveliest tones. The extraordinary monochromatic iridescence of the scarab gave it a divine status in its representation of Khepri, the solar aspect of the great god Ra. The Egyptians also had a highly refined cosmetic art, the products of which, including extravagantly colored powders and creams, were exported throughout the ancient world. Precious stones, objects of the purest and most translucent colors to which they had access, were used in sacred rituals and for healing.

Figure 1.4. The sacred scarab Khepri, a solar deity

The “Evolution” of Color

Our extreme sensitivity to color is encoded in our genes as a result of an evolutionary process dating back hundreds of millions of years that informs our sense of vision. Zoologist Andrew Parker (2003) has developed a hypothesis known as the light switch theory. This theory concerns the enigma known in paleontology as the Cambrian explosion; 543 million years ago, at the beginning of the Cambrian era, a 3-billion-years-long evolutionary process had led to the appearance of only three animal phyla (the highest level of taxonomic rank below kingdom). Barely five million years later—a mere wink in the geological scale of things—thirty-eight phyla were in existence, a number that has hardly changed since that time. This fact has not been properly explained by the larger scientific community; however, Parker says the explanation is directly linked to the appearance of the sense of vision. Until that time many creatures had been well equipped with photosensitive cells in their organs (even bacteria had some) that were capable of distinguishing between light and dark. But the first creature known to have possessed a real eye—that is, a system of vision capable of perceiving an image—is the trilobite (Schoenemann et al. 2017), a little arthropod no longer in existence today, but whose appearance on the evolutionary scale corresponds exactly to the beginning of the Cambrian explosion. Because vision gave such an advantage to those creatures who had managed this step forward, it produced a veritable “arms race” among all animal life of that era, resulting in a hitherto unseen acceleration of the evolutionary process.

Figure 1.3. Left, the trilobite (photo by Tim Evanson) and right, its eye (photo courtesy Moussa Direct Ltd.)

Whatever happened exactly, there is no doubt that as a result of the emergence of vision a multitude of vegetal as well as animal life-forms adorned with an infinite variety of colored features began to appear. Whether to attract or to threaten, the more intense a color in terms of standing out from the background environment, the more chance it had to be perceived by this extraordinary new sense of vision.

Life-forms responded by developing a great number of chromophores, which are portions of biological molecules absorbing or reflecting light in a selective manner to produce a variety of different colored pigments. Also emerging were regular networks at the microscopic level that interfered directly with light rays to obtain structural colors that are of a perfectly pure iridescence, such as those in the feathers of a peacock or a hummingbird. Simultaneously occurring within this dance of evolution, the eyes and their interconnecting visual brain structures refined their sensitivity in such a way as to enable them to detect with ever greater precision the whole spectrum of visible color and beyond.

And so it is for humans. The most brilliant colors fascinate us and inevitably attract us. For some civilizations these colors acquire properties that are almost supernatural. For example, those objects considered most essential and precious in the afterlife were carefully laid out in the tombs of the Cro-Magnons: next to food, arms, and talismans, one finds vividly colored beads.

India possesses an ancient and rich tradition of chromotherapy dating from at least 1500 BCE, according to the Atharvan Veda, which emphasizes the healing power of the colored rays of the sun. The very sophisticated traditional curative system known as ayurveda considers color to be a key element in its therapeutic arsenal—of the same importance as food and medicinal remedies—and it is to be applied as much to the skin as to the visual system.

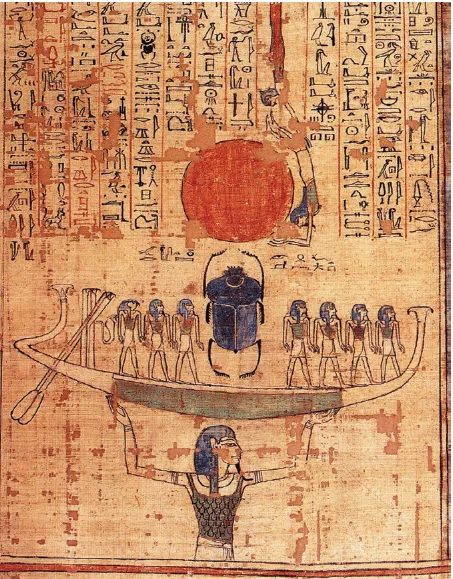

In the encyclopedic Canon of Medicine, completed in 1025, the great Persian physician Ibn Sīnā (known as Avicenna) gave much importance to the role of color for both diagnostic and treatment purposes. For example, he says that red stimulates the circulation of the blood, blue cools it, and yellow reduces inflammation and muscular pain.

Figure 1.5. Page from Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine (photo courtesy Wellcome Images)

My colleague Karl Ryberg, in Living Light: On the Origin of Colours (2010), a historical treatise on light therapy, points out that Avicenna benefited from the unsurpassed expertise of the glass workers of the Arabian world, who succeeded in creating panels of tinted glass of an unprecedented chromatic purity and translucence, far superior to the more opaque glasswork that had been made in an earlier time by the Egyptians or Babylonians. Of special interest is that Avicenna devised a treatment alcove that allowed his patients to bathe in the rays of the sun that were filtered by glass panels of these new crystalline colors.

To have perfected the technique of producing such colored glass was significant because it gave impetus to the healing potential of colored light. The Venetians, whose commercial empire held a monopoly on this technology imported from the Orient, jealously guarded their privilege. The artisans of Murano, who still create their celebrated Venetian glass, were held to secrecy under pain of death with regard to their technique. Inevitably, the secret got out, and from the twelfth century on the most stunning stained glass windows made their appearance in the churches and cathedrals of Europe. The incomparable purity of their light was considered to be of heavenly origin, and they became an essential element in the great Gothic cathedrals, offering grandiose masterpieces such as the rose windows of Chartres, or Notre-Dame in Paris. It is said that when people suffering from physical or ment...