![]()

chapter two

NUTRITIONAL PRACTICES

According to Tibetan tradition, the first illness ever recorded was indigestion. The cure was warm water. Thus a causal link between health and what we eat and drink was established.

Correct nutritional practices are a part of the first level of Tibetan medicine, which, as stated in the Introduction, pertains to lifestyle changes. Such practices are considered the least invasive and are, therefore, recommended first or if an illness necessitates greater intervention, in addition to more invasive therapies. Emphasis on lifestyle reminds people of their responsibility regarding disease.

Although it receives more attention in our culture now than previously, the importance of proper nutrition for maintaining good health is still not fully recognized in mainstream society. For the most part, modern clinical nutrition uses the model of the “four basic food groups” and a modern medical model that assesses food for its biochemical composition. The focus is on active ingredients such as vitamins and minerals and the specific effects these substances have on the body. Alternative medical models that use conventional knowledge of biochemistry, as well as focus on the benefits of whole, less processed foods, have become more accepted and have had an impact on conventional medical practices. Still, much of what is recommended in both conventional and alternative health communities is an oversimplified approach to nutrition. Broccoli is good for you. Brown rice and more fiber is what you need. Eggs contain cholesterol, a no-no. What is lacking in this approach is a sensitivity to constitutional variation and how this influences health and illness. For example, there are over a dozen forms of arthritis identified in the Ayurvedic tradition. Depending on the balance of the nyepas due to this condition and the rang-zhin of the person, what is recommended as food, medicine, and therapy will vary.

Perhaps in the early days of medicine in the West, when allopathy was a younger brother to naturopathy and homeopathy, there was a sensitivity to such variation, and the dictum “let your food be your medicine and your medicine, food” was taken seriously. In those times Western culture was more rural, hence agrarian. As we have become urbanized and out of touch with our natural environment, our respect for the elements of which we are a part has been lost. In such a climate allopathic medicine has ascended to a position of almost supreme authority. Losing touch with our natural environment, rhythms of life, and the importance of daily diet and behavior, afflictions such as colds and flus are considered inconveniences in our busy lives. Nature becomes the enemy, and allopathy becomes the hero, with the use of antibiotics, antihistamines, and so forth to keep nature from reclaiming its rightful territory. Ironically, in the end nature does triumph as our symptomology becomes more complex and deep seated. Chronic degenerative disease is the hallmark of modern industrial society. Inevitably this leads to runaway medical costs since interventions need to be more invasive and convalescence prolonged. Although we think that lifespan has increased in modern times due to improved medical care, this is a myth. Improved sanitation has had more impact on health than modern medicine.1 We have also lowered the infant mortality rates, which accounts for an average longer life expectancy. At the same time, however, we have fewer healthy eighty and ninety year olds; for the most part the senior citizens of our times are more debilitated than in the past. Perhaps we have too readily come to accept this situation as the norm.

The cornerstone of Tibetan medicine and nonconventional health practices today is individual responsibility. Such responsibility should not be considered burdensome. Indeed, being responsible implies being “able” to “respond,” to pay attention and reflect on what works and what doesn’t work in one’s life.

Correct nutritional practices are an obvious place to start. Why? Because selecting, preparing, and eating food is something we do every day and thus plays a major role in how our body functions. Consequently, following good nutritional practices is the first and foremost preventive health-care measure we can take.

Several factors come into play when considering proper nutritional practices.

- your rang-zhin, or constitutional type

- your present condition

- your level of activity (i.e., physical, sedentary)

- environmental factors

With these basic considerations in mind, we need to look at types of foods, qualities of food and food combinations, as well as when and how we eat.

The following are guidelines to address basic considerations and eating practices, including nutritional recommendations for each of the six constitutional types. At the end of these guidelines, we shall look at factors that indicate whether such dietary practices will work for you.

TASTES

There is more to taste in life than sweet and salty. In Ayurveda and in Oriental healing in general there are five tastes: sweet, sour, pungent (hot), bitter, and salty. When a food does not fall within the properties of these five tastes, it is considered astringent.

Tastes affect the nyepas. They nourish the organs in different ways. Consequently, certain tastes are emphasized in the nutritional recommendations for the different rang-zhins and when there is a specific organ imbalance. The following classifications show which tastes are associated with each of the individual nyepas.

RECOMMENDED TASTES (in order of preference)

LUNG – sweet, salty, sour, pungent

TrIPA – bitter, sweet, astringent

BEKAN – pungent, sour, salty

Combination nyepa-types will work with such information based on the presenting symptoms at any given time. For example, if a LUNG-TrIPA has TrIPA symptoms, the emphasis of the tastes should be those for TrIPA.

Although the food lists presented later in this chapter are extensive, you can expand your dietary practice by considering these taste qualities when selecting foods for your rang-zhin that are not on the lists.

QUANTITIES OF FOOD

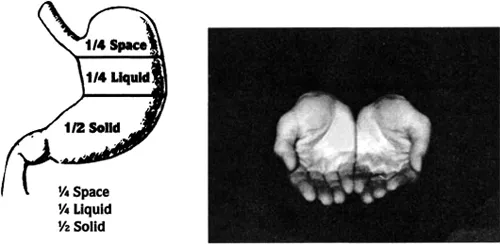

Quantity of food here means actual volume. Generally, the amount of solid food you consume should fill two parts, or half, of your stomach. If you were to place your hands together to form a bowl, the amount of food that would fit into your hands would be the amount of solid food you should consume.

One part of your stomach should be for liquid and one part for space. Space allows for food to mix more easily and thus metabolize more efficiently. If there is less space, foods may putrefy, creating excess BEKAN in the form of mucus.

The quantities of specific foods you should consume depend on where you live and what types of food exist in your region:

1) Foods from wet or humid regions (coastal and tropical) such as seafood and watery fruits and vegetables tend to be heavy and have a tendency to stagnate in the digestive process if overeaten.

2) Vegetables, fruits, and meats from high and dry regions are light and warming and thus can be eaten in more generous portions.

SEASONAL CONSIDERATIONS

During the summer you should follow the above guidelines strictly whereas in winter, because our pores close up and heat is stored, you have more heat to burn more fuel. Thus you can eat more heartily at this time. Chapter 14 of the Ambrosia Heart Tantra elaborates on dietary modifications recommended as the seasons change. These recommendations are based on the taste quality that enhances strength and vigor throughout the passage of time:

In short, take warm food and drink during monsoon and winter, rough [nourishment] in the spring and cool [food] in early summer and autumn. During the monsoon and winter, take [foods having] the first three flavors [of sourness, saltiness, and sweetness]; in the spring, use the latter three flavors [of bitterness, hotness, and astringency]; and in the autumn, take sweet, bitter, and astringent [foods].2

Although not as elaborate, standard macrobiotic recommendations of eating what grows in your climactic region and in season are consistent with Tibetan medicine. Several books on macrobiotics are listed in the Bibliography and are useful to read along with the material on Tibetan medicine and nutrition.

CHEWING

Lino Stanchich, an internationally respected macrobiotic counselor has written an excellent book entided The Power Eating Program, in which he discusses the importance of chewing in the context of nutritional practices.

Chewing affects our metabolism and proper utilization of foods in several ways. First, salivary amylase in our mouths helps break down the starches in grains, vegetables, and fruits into simple sugars. This allows for more efficient use of the energy in carbohydrates. It also allows the stomach and small intestine to focus on protein metabolism without the burden of dealing with starch. Chewing also makes the bones in the skull move more. The temporal lobes of the skull pump as the jaw moves rhythmically up and down. This has a positive effect on the hypothalamus. Thus, endocrine balance and nervous system strength are also enhanced.

Stanchich recommends that people chew each mouthful 75 to 150 times, the latter being preferred. This is especially true for weak or ill individuals. Energy expended in the process of chewing prevents the body from losing heat and energy in the digestive tract and thus aids in the preservation and utilization of metabolic heat, pho thut (Tibetan), or agni (Sanskrit), in an efficient manner. In addition, chewing slows down the eating process, which allows us to focus on mealtimes as a nutrifying event rather than something that needs to be done while we’re on the run.3

FOOD SELECTION AND PREPARATION

Cooking is alchemy. You take the elements that have come together as foods in nature and through selection, preparation, and cooking methods create tastes and textures that can be both delightful to the palate and fortification for the body.

The best source for learning how to cook according to constitutional types is Amadea Morningstar’s The Ayurvedic Cookbook (see Bibliography). The most useful books on food quality, selection, preparation, and cooking techniques are written by macrobiotic authors such as Anna Marie Colbin and Rebecca Wood—to name two outstanding ones (see Bibliography). The following nutritional practice guidelines will be more effective when using these sources for guidance and inspiration.

To date very little has been written about Tibetan cooking. And there is the impression by many who come into contact with Tibetans that all people ate in Tibet was tsampa (roasted barley flour), meat, cheese, and Tibetan tea. Although these foods were indeed the common fare for most people, they do not reflect the cuisine of the privileged nor the variety of foods and preparation methods found in the medical tantras. Another question people have about Tibetan diet is that, given the fact that Tibetan culture became Buddhist, why were Tibetans such heavy meat eaters? The answer can be found in an understanding of the terrain of Tibet and a macrobiotic awareness.

A Tibetan doctor pointing out features of a diagram showing chakras and energy flow. Photograph © by Marica Keegan.

In such a high, dry mountainous climate, there were very few vegetable products, except some grains such as barley and wheat. Also, in a climate where the body is exposed to such extreme natural forces, the consumption of animal food such as dairy and meat products is a way of insulating the body. Unfortunately, this macrobiotic principle has not been well understood by Tibetans who have become refugees in less harsh climates. Such refugees have kept their diet as it was in Tibet, resulting in an increase in digestive, circulatory, and respiratory problems. There are elements of Chinese and Indian cuisine in the nutritional recommendations found in Tibetan medical literature, and to date it is the Ayurvedic cuisine being introduced into the Western world that comes closest to Tibetan cuisine.

When selecting food, it is best to shop at natural ...