![]()

1

A Brief History of Silver

Metallic silver has been known since antiquity. The oldest known silver artifacts date from the fourth century BCE. The Egyptians were probably the first to use silver for medicinal purposes. We know silver also found its way into ancient Greek, Roman, Persian, Indian, and Chinese medicine. Hippocrates believed that silver healed wounds and controlled disease. He listed as a singular treatment for ulcers “the flowers of silver alone, in the finest powder” (Rentz 2015). Herodotus describes how the king of Persia carried with him boiled water in silver flagons to prevent sickness. In the Americas, the Inca, Maya, and Aztec peoples used silver both for creating cult objects and for ornamentation, and there is evidence that ancient Incan and Muiscan surgeons performed cranioplasty using precious metals and gourds. Indeed, the quest for gold as well as for silver was part of the reason Spain colonized these indigenous cultures of the Americas.

SILVER DURING THE MIDDLE AGES

The different ways that silver was used during the Middle Ages were largely shaped by influences stemming from antiquity and Arabic alchemy. It was not until the sixteenth century, with the introduction of Paracelsus’ (1493–1541) concept of spagyrics, that this changed. Swiss-German physician, botanist, alchemist, astrologer, and occultist Paracelsus (né Philippus Theophrastus Bombast) first coined the term spagyric to refer to an herbal medicine produced by alchemical procedures that involve fermentation, distillation, and the extraction of mineral components from the ash of a plant. Paracelsus associated the seven metals (gold, silver, mercury, copper, iron, tin, lead) with the seven planets (sun, moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn), and in turn with seven different parts of the body, and even with certain foods.

If you have the Astrum of Mercury, in the same manner, you will tinge the whole body of common Mercury. If you have the Astrum of Venus you will, in like manner, tinge the whole body of Venus, and change it into the best metal. These facts have all been proved. The same must also be understood as to the Astra of the other planets, as Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Luna, and the rest. For tinctures are also prepared from these: concerning which we now make no mention in this place, because we have already dwelt at sufficient length upon them in the book on the Nature of Things and in the Archidoxies. So, too, the first entity of metals and terrestrial minerals have been made, sufficiently clear for Alchemists to enable them to get the Alchemists’ Tincture. (Paracelsus)

Because he associated silver with the moon, and mercury (i.e., quicksilver) with Mercury (the planet), Paracelsus pioneered the idea of using silver amalgam for medicinal purposes, such as in detoxifying baths.

Several hundred years earlier, writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, visionary, and polymath Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) viewed silver through the lens of the ancient doctrine of humoral pathology. She considered it a potent remedy for treating congestion and the coughing that results from it. She characterized silver as sharp and cold. In the ninth book of her Physica, titled “Metals,” she notes:

Silver (argentum) is cold, [because it contains cold wind, which makes even the earth cold]. A person who has in him a superfluity of humors, which he often expels [by coughing them up], should heat very pure silver in the fire and, thus heated, put it in good wine. He should do this three or four times, so that the wine gets hot from it. He should drink it often, heated this way, before breakfast and at night. It will diminish his superfluous humors.

[The strong natural cold of silver diminishes hot, cold, and moist humors by its sharpness, joined with the heat of the fire and the heat of the wine, altered as described.] (Bingen 1998, 238)

In the fourteenth century, Conrad von Megenberg, a polymath and canon of Regensburg, wrote in part 7 of his Book of Nature,

Silver also has the ability to fuse other metals together and make one piece from two. When ground and mixed with precious ointments, it can be used against that viscous moisture in the body known as phlegm. . . . Silver is pure, but less so than gold. . . . Although it is white, it has the property of blackening other things that scratch it. Its slag, called scoria in Latin, can be used to treat scabies and hemorrhoidal bleeding. (Megenberg 1897, 478)

It should be added that Megenberg’s reports on the effectiveness of silver in treating metabolic weaknesses, itching, and hemorrhoidal complaints are in complete agreement with Hildegard von Bingen’s earlier accounts.

Until the time of Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843), the founder of homeopathy, preparations of silver had found only limited medical use. Hahnemann himself was slow to acknowledge silver’s many benefits. In his 1798 Apothekerlexikon (Pharmacist’s Lexicon), one of the standard reference works of homeopathy, Hahnemann still reflected an earlier era’s views about silver’s limited application in medicine: “A pharmacist will occasionally wrap silver leaf (Argentum foliatum) around their pills as a kind of luxury, a procedure that makes this form of medicine, which is already difficult for our stomachs to digest, only that much more indissoluble and ineffective” (2:216 ff.). In his subsequent works Hahnemann began to demonstrate a growing interest in silver’s efficacy, describing two forms of silver nitrate, as metallic silver had not been used in medical practice before his time. By 1820, however, Hahnemann expanded the role of silver in homeopathy by introducing triturated colloidal silver, which he called

ARGENTUM METALLICUM metallicum, describing this as a “sensible medicament” for treating patients.

Silver in Folk Medicine

In European folk medicine, ancient ideas about silver commingled with various demonological notions that arose during the medieval period. A mixture of these beliefs continued to shape the ways in which silver was used all the way up until the early twentieth century, especially in the Alps, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean regions, as illustrated by this passage from Ulrike Müller-Kaspar’s 1999 book, Handbuch des Aberglaubens (Handbook of Superstitions): “Silver has the power to ward off demons and illnesses, whereby silver that has been inherited over many generations is particularly powerful. Wearing rings of silver is an especially useful apotropaic means of fighting off various illnesses. Finely ground silver, mixed with various plants, is said to be useful in treating rabies, nosebleeds, dropsy, etc.” (Müller-Kaspar 1998). Thus in some ways silver is still used today just as Dioscorides and Megenberg recommended. The manner in which Paracelsus and the other early modern alchemists used silver apparently had little impact on European folk medicine because the theoretical justifications they supplied for its use were too abstract.

MODERN SCIENCE CONSIDERS SILVER

In 1861, Scottish chemist Thomas Graham (1805–1869) described the differences between colloids that were capable of passing through membranes and precipitates that were unable to do so. Graham’s discovery was that substances could enter a solution in such a manner that they exhibit characteristics that are quite different from those of a true solution. He applied the term colloidal (from kola, “glue”) to this intermediate state, as glue, gelatin, and related substances were the most obvious to him as being in this unique state. Graham’s study of colloids was foundational in the field known as colloid chemistry, and he is credited as its founder.

In 1869, French scientist J. Ravelin noted that even low doses of silver produced antimicrobial effects. In 1881, Carl Siegmund Franz Credé (1819–1892), a gynecologist from Leipzig, recommended administering eye drops containing 1 percent silver nitrate to newborns to prevent them from developing ophthalmia, a form of conjunctivitis common in neonates, which can cause blindness. Both because of its success and because better alternatives were lacking, the use of what became known as Credé’s prophylaxis was made mandatory in several countries and became a standard practice in obstetrics. By 1897, silver nitrate began to be used in the United States to prevent blindness in newborns, a practice that was eventually replaced by the use of modern antibiotics.

In 1893, Swiss botanist Karl Wilhelm von Nägeli (1817–1891) characterized the properties of silver as oligodynamic, which simply means “active in very small quantities.” Nägeli determined that concentrations of as little as 0.0000001 percent silver ions were sufficient to kill a freshwater pathogen (Spirogyra) and other living organisms such as algae, molds, spores, fungi, prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms, and even viruses.*2 In 1910, Dr. Henry Crookes reported that certain colloidal metals

have a highly germicidal action but are quite harmless to human beings. . . . The greater the extent to which the metal is set free in a very dilute solution of its salts, the greater is the germicidal power of the solution! By converting the metal into a colloidal state it may be applied in a much more concentrated form and with correspondingly better results. (Searle 1920, 68)

In 1919, the prolific author, editor, and translator Alfred B. Searle wrote in The Use of Colloids in Health and Disease, “The germicidal action of certain metals in the colloidal state having been demonstrated, it only remained to apply them to the human subject, and this has been done in a large number of cases with astonishingly successful results” (Searle 1920, 75).

In all, more than ninety-six different silver medicinals, many used intravenously, were in use prior to 1939, as documented by the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry of the American Medical Association (Rentz 2015).

In the 1970s, Dr. Robert O. Becker (1923–2008), an orthopedic surgeon and medical research doctor, studied the effects of colloidal silver on electrochemical processes in the body. He wrote about his research on the medical applications of silver in several best-selling books, including The Body Electric, and also published numerous articles about the efficacy of silver in various scientific journals.

Silver . . . killed or deactivated every type of bacteria without side effects, even with very low currents. We also tried the silver wires on bacteria grown in cultures of mouse connective tissue and bone marrow, and the ions wiped out the bacteria without affecting the living mouse cells. We were certain it was the silver ions that did the job, rather than the current, when we found that the silver-impregnated culture medium killed new bacteria placed in it even after the current was switched off. The only other metal that had any effect was gold; it worked against Staphylococcus, but not nearly as well as silver. (Becker and Selden 1985, 167)

Dr. Becker could arguably be said to have pioneered the current resurgence of scientific interest in the use of silver in medical applications. His primary area of personal interest had always been exploring the possibility of complete tissue and organ regeneration in humans. Through his fascinating journey, which spanned over three decades of dedicated research, he brilliantly explored bioelectric and electromagnetic systems, reaching to understand and control the growth and healing process in complex organisms. Before Becker’s research group dissolved, Dr. Becker found that silver ions, electrically injected, could suspend the mitosis of (cancerous) malignant fibrosarcoma cells. Dr. Becker hypothesized that cancer cells, regardless of the initial cause, were cells caught in a partially differentiated and primitive state. Unfortunately, this promising research was never fully explored.

However, other researchers picked up on the trail of research initiated by Dr. Becker, and in chapter 3 we will look at some of the numerous studies that have been done in recent years on the viability of silver in a host of medical applications. But first, let’s take a look at how silver, one of the earth’s most valuable precious metals, is formed and extracted.

![]()

2

The Geology, Physics, and Extraction of Silver

The primary means by which silver is produced in nature is through hydrothermal processes occurring in sulfide deposits, since silver is formed by forming compounds with sulfur. For this reason, the most common primary sources of silver are formations that also contain lead, as well as those containing copper, gold, and zinc. It is also found in its free form, as silver.

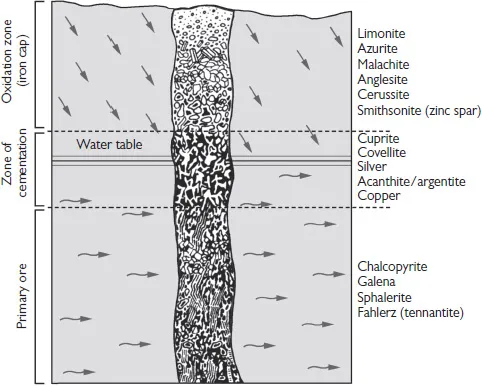

Secondary sources of silver include the oxidation zone of the gossan, intensely oxidized, weathered, or decomposed rock, usually the upper and exposed part of an ore deposit, often called iron cap (from the German eiserner hut, referring to the area close to the surface), and the zone of cementation that lies below the gossan. Here, sulfide deposits that contain silver can be precipitated as the rocks that lie above decompose through weathering. Such silver deposits are often found together with argentite, pyrargyrite, and stephanite. Secondary sediments are usually fine in structure, although they may also be found as a cement or in sheets of copper-bearing sandstones or sapropelic copper ores. Most alluvial deposits of heavy metals contain only insignificant amounts of silver.

The abundance of silver in the earth’s crust has been calculated to be 1×10-4 percent by weight = 0.1 gram per ton, making silver some ten times more abundant than gold. Additionally, saltwater contains 0.3 to 10 milligrams of silver per cubic meter, or approximately 1/100th parts per million (ppm).

Fig. 2.1. Zone of cementation

SILVER ORES WITH A CONTENT OF MORE THAN 45 PERCENT SILVER

The International Mineralogical Association currently recognizes 128 minerals as being silver materials, in which silver is incorporated directly into their crystal lattices. The most important of these have a silver content greater than 45 percent. They include:

Acanthite: Ag2S, silver sulfide; black, metallic luster; hardness (Mohs scale) 2–2.5; specific gravity 7.22; molecular weight 247.8 = 87.06 percent silver.

Argentite: Ag2S, cubic silver sulfide; silver gray, metallic luster; hardness 2–2.5; specific gravity 7.2–7.34; molecular weight 247.8 = 87.06 percent silver

Dyscrasite: Ag3Sb, silver antimonide; silver white, metallic luster; hardness 3.5–4; specific gravity 9.4–10; molecular weight 445.36 = 72.66 percent silver

Empressite: AgTe, silver telluride; pale bronze, metallic luster; hardness 3.5; specific gravity 7.6; molecular weight 235.47 = 45.82 percent silver

Eugenite: Ag11Hg2, silver-mercury; white; hardness 2.5; specific gravity 10.75; molecular weight 158.75 = 74.73 percent silver

Hessite: Ag2Te, disilver telluride; lead gray, metallic luster; hardness 2–3; specific gravity 8.24–8.45; molecular weight 343.34 = 62.83 percent silver

Luanheite: Ag3Hg, silver-mercury; gray; hardness 2.5, specific gravity 12.5; molecular weight 524.20 = 61.73 percent silver

Naumannite: Ag2Se, silver selenide; grayish black; hardness 2.5; spec...