![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Early Years

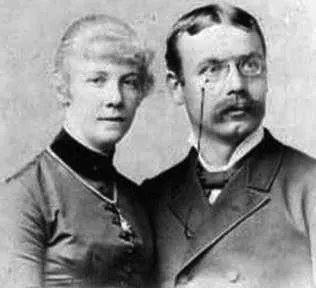

Erwin Johannes Eugen Rommel, the future Desert Fox, was born in Heidenheim, Wuerttemberg, in the southwestern region of Imperial Germany known as Swabia, a few miles north of Ulm, on November 15, 1891. He was the third of five children born to Erwin Sr., a teacher and headmaster of a secondary school, and his wife Helene. Like many German fathers in that day, Erwin’s father was a strict parent, with a walrus mustache and slicked-down hair parted in the middle. The thing Erwin remembered most about him was that he was always asking educational questions, which annoyed his son, who had little enthusiasm for academics.

Young Rommel’s mother, Helene von Lutz Rommel, was the oldest daughter of the president of the provincial government of Wuerttemberg. However, Herr Rommel did not want a political career, as such a match might imply. Erwin Sr. wanted to settle down with his bride, have a family, and enjoy a stable, comfortable middle-class German life—and that is exactly what he did.

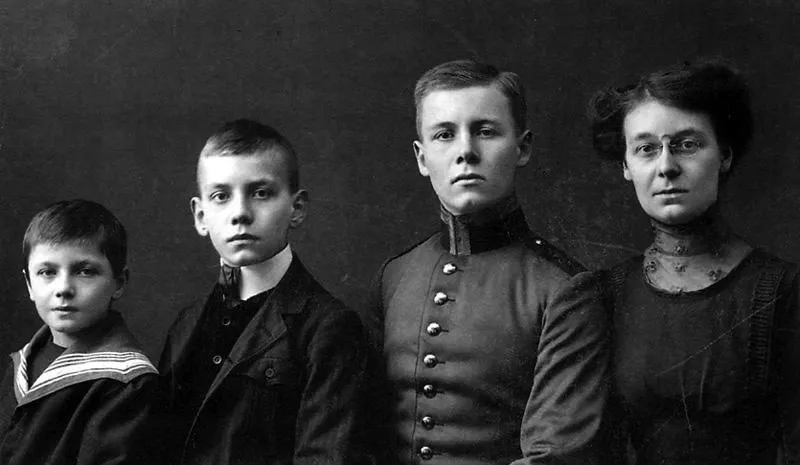

Their first child, Manfred, was born in 1888 but died young. The second child, Helene, became a teacher like her father and never married. The future field marshal was the third child. He was followed by Karl, who became an airplane pilot, flew combat reconnaissance missions during World War I in Egypt and Palestine, and earned several decorations before malaria crippled him. He died on August 22, 1918.1 Rommel’s youngest brother, Gerhardt, was the black sheep of the family. He aspired to be an opera singer but never achieved much success, on stage or off.

Rommel’s parents, Erwin and Helene. Professor Rommel died in 1913. Frau Rommel did not pass away until 1940.

Rommel was weak and sickly as an adolescent. He didn’t like to play games with the other children. He preferred to keep to himself, daydreaming. He had no interest in athletics, girls, or hobbies. He was a lethargic child and a mediocre elementary school student at best. A teacher once remarked that if Erwin ever earned 100 percent on a spelling test, he would declare a school holiday. For once, the future field marshal sat straight up at his desk. Although the instructor was being sarcastic, Rommel took him seriously. Before long, another examination was given and this time the future Desert Fox spelled every word correctly. But when the promised holiday did not materialize, he relapsed into his lassitude. Then, as a teenager, Erwin Rommel suddenly woke up. He started a physical fitness program and systematically conditioned his body, much as young Theodore Roosevelt did. He exercised, played tennis, bicycled, and learned how to ski and ice skate. Before long, Erwin was exhibiting the characteristics of a typical Swabian: self-reliance, pragmatism, thrift, a strong work ethic, and a stubbornness bordering on pigheadedness. He was a simple person and would remain unsophisticated until the day he died.

Rommel’s childhood was secure, comfortable, and unremarkable. From his teenage years until the end of his life, Rommel focused on the practical, rather than on philosophy, theory, or religion. (Rommel was Evangelical Lutheran but not very demonstrative about his faith.) Under other circumstances, he would have made a fine engineer: at the age of fourteen, he and a friend built a full-size glider in a field near Aalen, and it actually flew, although not very far—a remarkable achievement for a pair of teenagers, especially in 1906, only three years after the Wright brothers’ historic flight.

As he neared the time for higher education, Erwin Rommel had to choose a career. He and his father discussed the matter, and two choices presented themselves: a military officer or a teacher. Rommel decided to become a soldier. At first his father was not convinced this was the wisest choice. There was no military tradition in the family except in the case of Professor Rommel himself, who had been a reserve lieutenant of artillery. But when he saw that his son’s mind was made up, he supported him and wrote him a letter of recommendation.

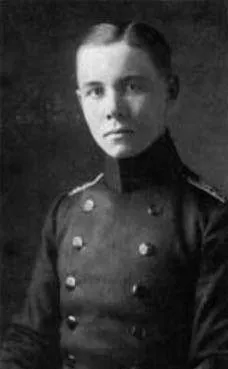

The young man had a definite knack for mathematics, so he applied for an appointment as a Fahnenjunker (literally officer-cadet, that is, an officer candidate) in the engineer branch, but he was rejected. An application to the artillery branch met with the same fate. Finally he applied to the infantry, the toughest and least romantic of all the branches. Here he was accepted. Erwin Sr. had to agree to pay for his son’s initial upkeep, to pay for a minor operation to correct a hernia, and to buy him a uniform. (In those days, junior officers served Kaiser and Fatherland pretty much at their own expense.) On July 19, 1910, the eighteen-year-old Swabian became an officer-cadet in the 124th (6th Wuerttemberger) Infantry Regiment at Weingarten in southwestern Germany.

The Rommel children, circa 1902: Gerhard, Karl, Erwin, and Helene.

Young Rommel was a handsome, blue-eyed, well-built man of just below average height. Alone and away from home for the first time, he met Walburga Stemmer, an eighteen-year-old fruit seller. She was not particularly good-looking, but the lonely young Rommel was drawn to her, and they became lovers.

Fahnenjunker Erwin Rommel, 1910.

In March 1911, after nine months of regimental duty, Cadet Rommel achieved one of his life’s ambitions: he was sent to the War Academy at Danzig to undergo officer training. Here, at Imperial Germany’s equivalent to Officers’ Candidate School, Rommel did well in rifle and drill work but was only adequate in gymnastics, riding, and fencing. His efficiency report noted that he was “rather awkward and delicate” but had immense willpower and was firm of character. It concluded that he would be “a useful soldier.”

At Danzig, Erwin Rommel met another girl, Lucie Maria Mollin. She was slender and very attractive, with a dark complexion, black hair, and a fine figure. Her deceased father had been a West Prussian landowner and the headmaster of a secondary school. Lucie was an excellent dancer and was in town to study languages. (She could speak French, Italian, Spanish, English, and Polish.) She considered Rommel too serious at first, but she soon fell for the handsome Faehnrich (senior officer-cadet), and they were apparently lovers by the time he received his commission in January 1912. She was Catholic and he was Lutheran, but they did not let religion get in their way. They considered themselves informally engaged when Second Lieutenant Rommel returned to his regiment at Weingarten. He and Lucie wrote to each other every other day, but this did not stop young Rommel from also resuming his affair with Walburga. Then, in 1913, Rommel received what was probably the greatest shock of his young life: Walburga Stemmer was pregnant.

When Erwin learned that Walburga was with child, he wanted to resign from the army and marry her, even though he had no way to support a wife and child. His family talked him out of it. Herr Rommel, who died later that year, wanted young Erwin to stay in the military, and his mother correctly considered Walburga—who was the daughter of a seamstress—unsuitable to be the wife of an officer in class-conscious Wilhelmian Germany. Also, it was evident that war might break out at any time. To resign at this point could well be interpreted as an act of cowardice, something Second Lieutenant Rommel could not abide. He broke it off with Walburga.

Gertrud Stemmer, Erwin Rommel’s first child, was born on December 8, 1913. Although he contributed financially to Gertrud’s support for the rest of his life, Rommel’s desire for Walburga cooled. He was in love with Lucie. He told her about his indiscretion. The exact details of what Erwin said to Lucie and vice versa have been lost to us, but we do know that Lucie forgave him and even accepted Gertrud as a member of the family after they were married.

Lieutenant Rommel and his daughter, whom he affectionately referred to as “Little Mouse,” remained close for the rest of his life. When World War I broke out in 1914, he instructed his sister Helene Rommel to look after Walburga and his daughter, and he listed Gertrud as the beneficiary of his life insurance policy. Walburga remained faithful to Rommel and convinced herself that he would return to her someday. She died in 1928.

After her mother’s death, Gertrud would spend a great deal of time with the Rommels. She was introduced to people as a cousin. During World War II, she knitted her father a plaid scarf, which he habitually wore during the Desert War. Gertrud kept in touch with Rommel until his death in 1944, and she remained close to Lucie and Manfred—Lucie and Rommel’s son—even after the war. It was not until Gertrud’s death in 2000 that her relationship to Rommel was discovered. She married and left behind a son (Rommel’s grandson), Josef Pan, who was seventy-two in 2012.

Walburga Stemmer and her lover, Lieutenant Erwin Rommel.

Lucia “Lucie” Mollin, about the time she became engaged to Erwin Rommel. Courtesy of Colonel Edmond D. Marino.

Back in Weingarten, Erwin Rommel had rejoined the 124th Infantry Regiment and was given the task of training new recruits for the 7th Company. He naturally did a good job, but his work would have been considered dull by many—training and drilling in a nondescript infantry regiment in an out-of-the-way part of Germany. His private life was equally uninteresting. He did not smoke, drink, or party with his young peers. On the job, he was all business. He had a hard streak, exhibiting no tolerance for the inefficient.

He also developed a certain class consciousness. This social awareness did not evolve into class hatred or reverse snobbery, for he had a number of aristocratic friends. However, he was somewhat suspicious of the aristocracy and had no use for officers who thought they should be granted rank and privilege just because of their social status.

Rommel was eventually attached to the 49th Field Artillery Regiment at Ulm (twenty-eight miles from Heidenheim) to cross-train in that branch.2 Ironically, his commander was the very officer who had rejected his application to join the artillery in 1910. Rommel was in Ulm when World War I broke out. He immediately rejoined the 124th Infantry Regiment as a platoon leader.3 Throughout Germany, and indeed throughout the entire continent, there was joy and singing. Europe entered World War I with a light heart; both sides were sure that they would win a decisive victory in short order.

Rommel and Lucie shortly after their marriage, circa 1917.

The 124th was ordered to the Western Front. Rommel had a chance to see his mother, two brothers, and sister for a few moments at Kornwestheim before the locomotive blew its whistle and it was time to say goodbye. That night they crossed the Rhine. The singing and excitement had died away, and Rommel wondered, “Will I ever see my mother and family again?”

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

The Great War

Rommel fought his first skirmish in the village of Bleid, Belgium. He had been on patrol for twenty-four hours and was suffering from stomach problems, as he often did in the 1914–15 period. Rommel had only three of his men with him (a sergeant and two privates), as opposed to around twenty Frenchmen in their forward outpost; he nevertheless dashed forward and started shooting. Several Frenchmen went down, and the rest dove for cover. Meanwhile, the rest of Rommel’s platoon arrived, and the fighting became house to house. Before it was over, the entire battalion had joined in. The Germans finally overran the village and took more than fifty prisoners. Although this small battle was insignificant in and of itself, it set the pattern of Rommel’s career—daring and boldness that would be seen on a much greater scale later both in World War I and in World War II.

Until now, Rommel’s career had been fairly average and routine. The battlefield changed him from an ordinary, if overly serious second lieutenant into a first-class warrior. As Desmond Young, who fought in the Indian Army against Rommel in Africa and went on to write the best-selling Rommel: The Desert Fox, would explain, “From the moment that he first came under fire he stood out as the perfect fighting animal: cold, cunning, ruthless, untiring, quick of decision, incredibly brave.”1 One of Rommel’s colleagues said, “He was the body and soul of war.”2

Meanwhile, in the fall of 1914, the Imperial German Army was pushing on toward Paris. They crossed the Meuse and, in the confusion, came across a huge number of wounded men in the woods. “We helped them regardless of whether friend or foe,” Rommel recalled. This theme was to be repeated throughout his career. Erwin Rommel believed in chivalry. He took care of the enemy’s wounded, giving them the same attention he gave his own injured. He never abused or mistreated prisoners and would not tolerate those who did. He was, however, amused that some of the Frenchmen were reluctant to surrender because they had been told that the Ge...