1.1Two patterns of pronunciation

The ultimate aim of this study is to deepen our understanding of what is sometimes called the “displacement property” of natural language (cf. Chomsky 1995, 2000, 2004). The basic observation behind this designation is that linguistic expressions can be pronounced at one place and function as if they are in others. Illustration is provided by the English sentence whom do you like,1where the following can be observed of the word whom: (i) it is assigned accusative case, (ii) it bears the thematic role of the liked person, i.e. the person receiving the addressee’s affection, and (iii) it satisfies the requirement that like have a direct object, in the sense that its absence would cause the sentence to be deviant in the same way that *you like is deviant. These are just the attributes associated with the position of her in you like her. One informal way to describe the facts, then, is to say that whom is present at two places: the post-verbal position, where it acquires the aforementioned attributes, and the clause-initial position, where it is pronounced.

Such “double existence” phenomena are attested in every language, and have been given various theoretical treatments in the course of generative grammar’s history. Uniting them, nevertheless, is the idea that sentences are derived by successive application of rules mapping one syntactic object to another, and that principles of grammar may apply to representations constructed at different points of the derivation. The theory proposed in Chomsky (1965), for example, distinguishes between the deep structure of a sentence, which determines its meaning, and the surface structure, which determines its sound. It is on the basis of the deep structure of whom do you like, which is approximately you like whom, that whom is identified as the direct object of like, assigned accusative case and given the appropriate thematic role. Application of syntactic rules to you like whom will yield whom do you like, the surface structure, which serves as input to phonetic interpretation.2The mapping from deep to surface structure, in this case, has an effect on whom which warrants the term “movement,” or “displacement”: whom disappears from one position (its base position) and reappears in another (its derived position).

| (1) | you like whom →whom do you like |

Thus, “displacement” is the name given to a phenomenon – i.e. one of linguistic expressions being pronounced in one place and performing functions dedicated to another – which reveals how this phenomenon is modeled in the theory, or more precisely in Chomsky (1965) (cf. also Chomsky 1955, 1957, 1964). Thirty years after the publication of this work, the phenomenon is still called “movement,” but its conceptualization has undergone a change. Instead of (1), we have (2).

| (2) | you like whom →whom do you like whom →whom do you like whom |

This, of course, is the Copy Theory of Movement (CTM),which analyzes movement of a constituent X as a sequence of two separate operations (cf. Chomsky 1993, 1995,Gärtner 1998, Sauerland 1998, 2004, Fox 1999, 2000, 2002, Corver and Nunes 2007). The first, call it Form Chain, copies X into the derived position, forming a chain (α, β) where α is the higher (i.e. c-commanding) and β the lower (i.e. c-commanded) copy of X. The second operation, Copy Deletion, maps (α, β) into(α, β): it deletes the lower copy, making it invisible to the phonology.

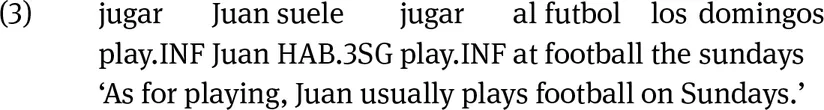

A question that arises naturally in the context of the CTM is then whether cases exist in which Form Chain applies but Copy Deletion does not, i.e. cases where a constituent exhibits properties of moved elements and at the same time is pronounced at both the derived and the base position. Several recent works have concluded that this question is to be answered in the affirmative (cf. Nunes 2003, 2004, Fanselow and Mahajan 1995, Fanselow 2001, Grohmann 2003, Grohmann and Nevins 2004, Grohmann and Panagiotidis 2004, Hiraiwa 2005, Martins 2007, Cheng 2007, Vicente 2005, 2007, 2009, Kandybowicz 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, among others). The conclusion is backed by examples of “doubling” such as the following Spanish sentence, from Vicente (2007:7).

Vicente shows that topicalization of verbs in Spanish is subject to the same locality conditions as, say, wh-movement in English. Nevertheless, the moved verbs are pronounced twice, at [Spec,C] and inside TP. Similar examples of doubling have been provided for other languages in the works cited above. Now, given that doubling exists, a second question poses itself: when does it exist? This study proposes a partial answer to this question. The rest of this chapter will be devoted to setting up the theoretical background for the formulation of this answer, as well as presenting the answer itself. The chapters that follow justify it with empirical observations.