![]()

PART ONE

BECOMING MARY SULLY

![]()

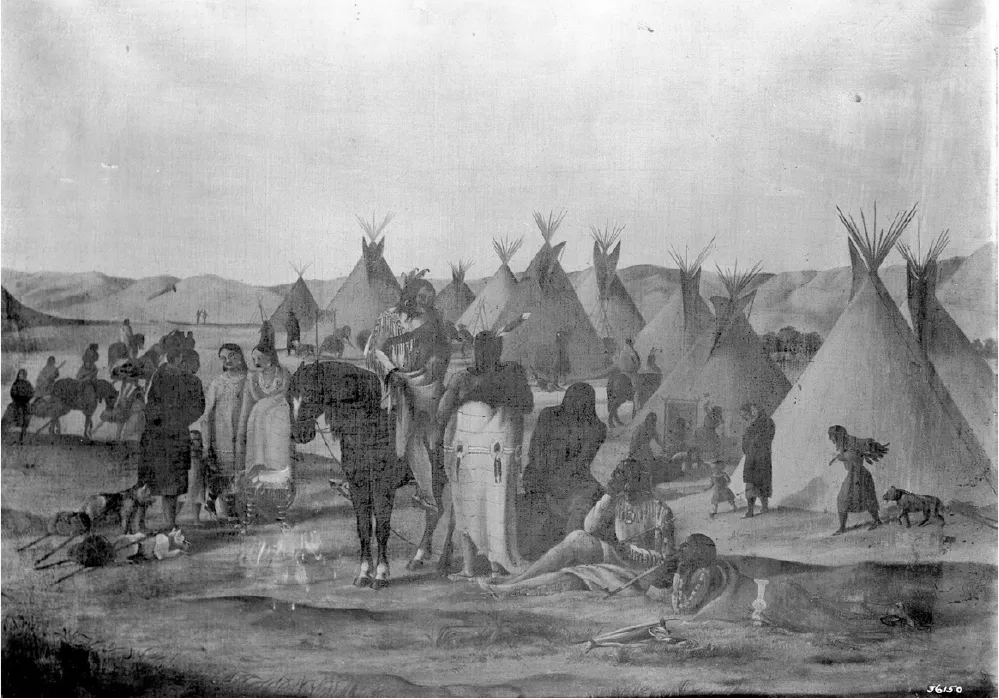

1.1.Alfred Sully (1821–79), Sioux Village Fort Pierre (1857). Oil on canvas, 21 × 29 inches. Photograph by Ira W. Martin. Frick Art Reference Library Negative 36150

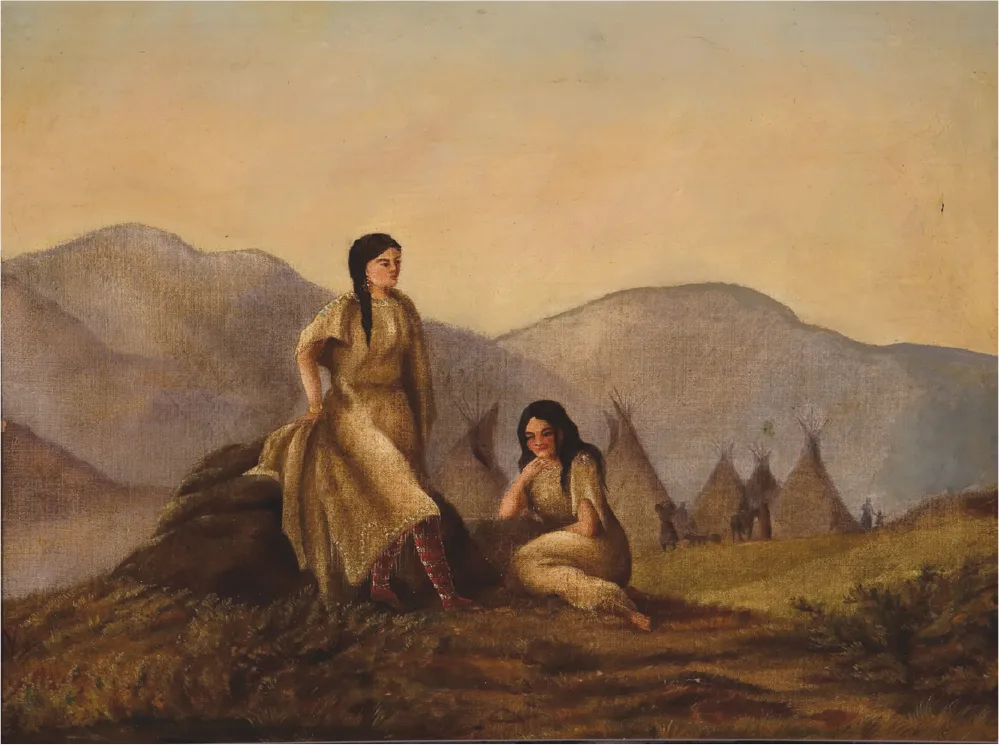

1.2.Alfred Sully (1821–79), Dacota Sioux Indian Encampment (1857). Oil on canvas. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska. Given in memory of Jasper L. Hall by Mr. and Mrs. Edward W. Aycrigg. 1966.358

1.3.Alfred Sully (1821–79), Sioux Indian Maidens (1857). Oil on canvas; overall: 22 × 36¾ × 2¼ in. (55.9 × 93.3 × 5.7 cm). Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma. GM 0126.1100

CHAPTER ONE

GENEALOGIES

Sound from Everywhere

IN APRIL 1857 COLONEL ALFRED SULLY SENT A BOX TO HIS FAMILY IN Philadelphia, posted from the ragged military station at Fort Pierre, South Dakota. Inside were a letter, three paintings, and a pair of moccasins. “The big picture [see fig. 1.1] is taken from part of an Indian village when they are dressing buffalo skins,” Sully wrote, noting that the view out his window had provided the background for what was a composite image. Three of the figures were drawn from memory—likely three of the five figures that occupy the center of the image. Others, however, he proclaimed that he had painted from life: “The two girls are meant for likenesses. One near the horse is called Peh-han-lota or Red Crane, the other Ke-ma-me-lar or Butterfly. They are both right good looking girls & very well behaved.”1

The two young women jump out from the image, their light-colored fringed dresses framed by the black of the nearby horse and of the maternal figure standing to the left side of the picture. Indeed, the dresses—and thus the figures—stand in high contrast to the muted colors that characterize the remainder of the painting, and they seem qualitatively distinct. Unlike anyone else in the Sioux camp, these women are named in the letter, both in the Dakota language and in English translation. Sully knew them. He posed and painted them, judged their looks, and, in what we should probably read as an arch implication, commented on their “good” behavior.2

Indeed, Sully painted them more than once, for the other two paintings in the box featured the same two women. Dacota Sioux Indian Encampment (fig. 1.2) lives at a more intimate scale, suggesting that it too was drawn from life, focused in particular on one of the women who is identifiable through her clothing and facial features. And in Sioux Indian Maidens (fig. 1.3), he pursues them even more directly. Here the background has turned generic, with a featureless camp backed by towering, romantic mountains. The two women are explicitly posed; they are the subjects of the image. On the left, the woman who seems to be Peh-han-lota (Pehánlútawiŋ) stands strongly upright, wearing a dress that suggests buckskin (in the fringe near the arms and the hem) or cloth (in the looseness of the folds and flows); she wears the same horizontally striped socks or leggings visible in Sioux Village Fort Pierre and what seem to be shoes or slippers. Ke-ma-me-lar (Kimímela), whose dress matches that illustrated in the larger painting, sits demurely on the ground, barefoot, with legs tucked beneath her.

Sully offers viewers two contrasting representations of these Indian women. Neither reflect the laboring drudges often found in such images (though such women are visible in the backgrounds of both pictures, reflecting Sully’s internalization of this colonial gender ideology). Rather, Kimímela offers the demure sensuality attached to Indian princess figures, frequently portrayed as simply waiting for the right white man—with whom they will then cross (and affirm, and produce) sexual, social, and cultural boundaries. Pehánlútawiŋ, on the other hand, is strong, sturdy, confident. Connected to and emergent from a pile of stones, her head positioned amid the mountains and her feet solidly grounded, she is literally as solid as a rock, a noble Indian maiden.

It may seem curious that the question of footwear—stockings, leggings, shoes, moccasins, bare feet—should emerge from such images. But it does. One of the central visual linkages across the three paintings is found in the distinctive leggings and ambiguous footwear. The paintings literally shared their traveling box with a pair of moccasins. And in Sioux Indian Maidens, Kimímela seems to have removed her leggings and footwear altogether, the better to melt evocatively into the ground.

It is less curious that Alfred Sully should send his family such paintings, as he had made image making a regular part of his military career. An 1841 graduate of West Point, Sully served as an infantry commander during the Mexican War, during which he sketched military positions, landscapes, battles, and scenes of camp life. In his later career, he ventured into the more challenging work of oil painting, demonstrating that his limitations as a serious artist can simultaneously be read as a significant skill set for an amateur, working under often challenging conditions.

Sully arrived in the Dakotas following four years of military service in California in the immediate aftermath of the Mexican War. During that time, he “eloped with”—abducted might be another word—Manuela de la Guerra, the fifteen-year-old daughter of a Californio family that had befriended him while he served as an occupying officer in Monterey. Sully’s aggressive courting ran against the grain of Californio social convention, particularly since he had been a friend of Manuela’s mother, only five years his senior (and, in a strained marriage and soon to be a widow, perhaps a better match for the officer). In 1851, not long after the marriage, Sully experienced a three-part tragedy rich with colonial psychodrama: Manuela died shortly after childbirth, an event closely followed by the suicide of Sully’s African American servant (distraught, it was said, over the death of Manuela) and then by the death of Sully and Manuela’s newborn son, smothered while sleeping with Manuela’s mother. Sully left Monterey for a posting in Benicia, California, and eventually found his way to the Northern Plains in the fall of 1854, still bearing the imprint of this highly suspect tangle of death, in which colonial and social domination mixed with the tropes of romantic tragedy. It is hard not to see in the events a kind of final revenge of the repressed, in this case, of the slave, the conquered, and the vengeful parent—who might also have been a jilted lover. And as historian Stephen Hyslop has observed, Sully’s behavior also suggested a larger pattern: the three women who bore him children were all members of societies confronting military domination (Californio, American Indian, and Confederate), of which he was a prime instrument.3

Like many officers on the Great Plains, Sully was not averse to establishing temporary relationships with “right good looking girls” who were “well behaved.” At Fort Pierre and later Fort Randall, both frontier posts along the Missouri River, he would find opportunities among the Yankton people. For hundreds of years, Indian people and European commercial and military adventurers had understood the practical utility of cross-social marriage and alliance, which opened up networks of kinship and power. Sully’s relationship with Pehánlútawiŋ and Kimímela likely involved a broad range of exchange, cultural, social, and economic in nature. Indeed, even as Sully painted the women’s footwear—shoes, stockings, and moccasins—he portrayed it as a mode of exchange in his letter and offered material evidence of a trade: “To fill up the box I also send some mocassins made by the young Dakotah ladies and presented to me by them in the Indian fashion that is with the idea of getting me to give them something in return. Give them to whoever they will fit.”4

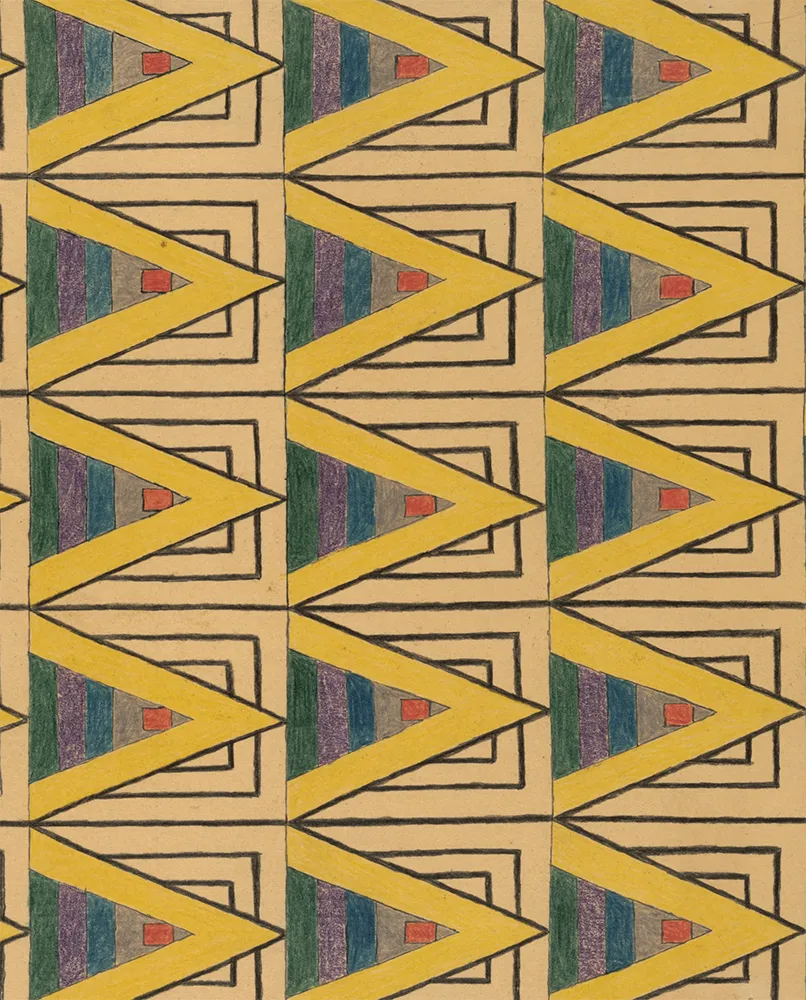

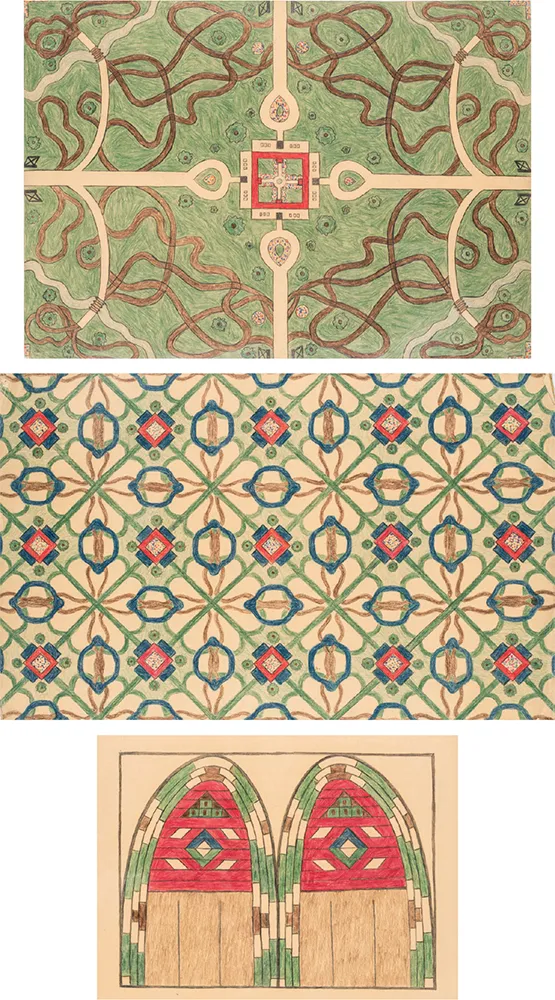

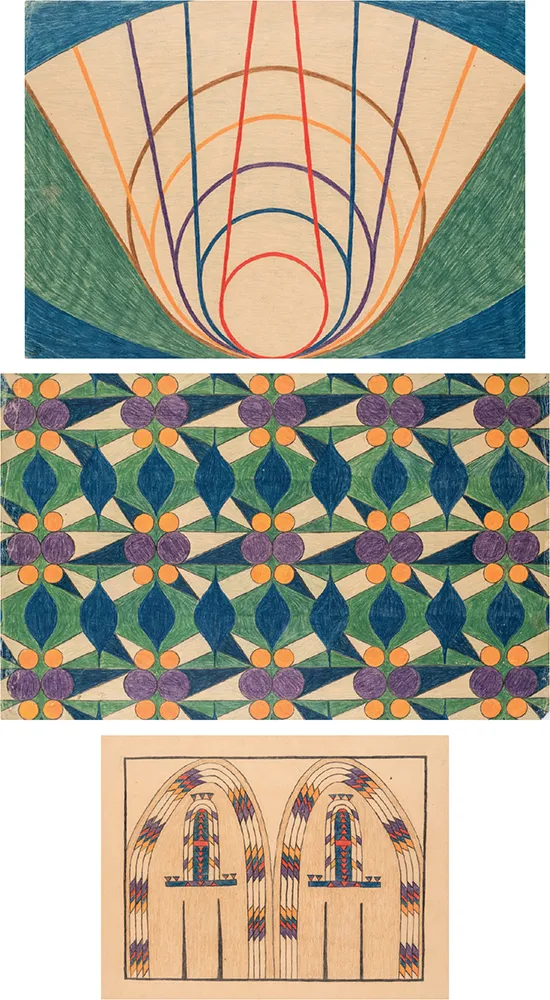

MARY SULLY AND FOOTWEAR

Mary Sully was heir to the traditions of quilled and beaded moccasin making, and she sometimes crafted bottom panels that turned from patterned design to representations of footwear itself. She figured Indiana writer George Ade in terms of his rural estate, with an overhead topographic view of rustic drives, footpaths, bridges, and trees. The bottom panel, however, is a gesture of honor and respect—red quilled moccasins, gifted visually from the artist to the generous subject, much as Pehánlútawiŋ had gifted Alfred Sully with a pair of moccasins of her own.

In Bobby Jones Sully makes a similar move, developing a highly abstracted pattern into a colorful design but then turning to pictorial representation: another pair of quilled moccasins. While most of Sully’s bottom panels are abstract designs, in a number of cases she did offer pictorial figures—many of which might be described as ethnographic in nature—drawn from Indigenous material culture.

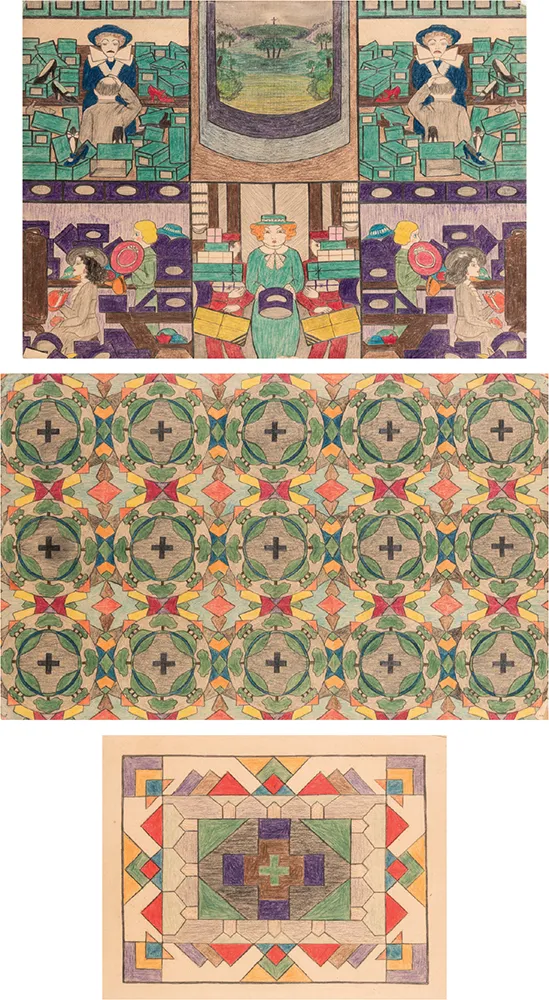

But Sully was also a habitué of the city. In Good Friday she captures New York as a place of conspicuous consumption. Indeed, the juxtaposition in Good Friday’s top panel between the grim crosses of Calvary and the haughty expressions of women unsatisfied by a proliferation of shoe choices offers both celebration and critique of the buying habits of the urban elite. The three crosses (echoed by three trees) in the top center are transformed in the bottom center into a parallel triad. Christ has taken the form of a wealthy shopper, while the two thieves appear as bellhops weighed down by packages, their strong horizontal lines refiguring the horizontal bar of the cross.

Pehánlútawiŋ and Alfred Sully engaged in an exchange and transformation of footwear, in which the respect represented by gifted moccasins was refigured by him first as a commodity (“getting something in return”) and then as a casual throwaway (“give them to whoever”). In George Ade and Bobby Jones, Sully invoked the more generous Dakota meanings that may have been encoded in Pehánlútawiŋ’s gift. In Good Friday, even as she celebrates the joy and color of a busy city, she also speaks cynically to the excesses of a world of goods and purchases. The day on which one remembers the death of Christ becomes the day on which one shops for shoes to wear on Easter, the day of the Resurrection. Even as Good Friday proclaims the life of the city, it also suggests an underlying hypocrisy, a contradiction between belief and action, between appearance and reality. Indeed, if one was to look back at Indian History through the lens of shoes, the top band of the top panel—a frightening collection of feet and legs—might leap out as yet another representation of domination. These meanings echo from the past, strikingly visible in the vexed relation between Alfred Sully and Pehánlútawiŋ and in the ways the military artist chose to represent it in both image and text.

Perhaps Sully offered the shoes and stockings shown in the paintings as a gift to Pehánlútawiŋ or Kimímela; one of these women likely offered the moccasins to him. Sully’s expressed view of the exchange was utilitarian, even crass: she gifted him out of self-interest, he thought, expecting something in return. Willing to have them distributed at random in Philadelphia, he attached little sentimental value to them. The view from the Dakota camps was likely quite different. Beaded moccasins were meant for family or ceremonial uses, not for sale or trade. Some—for babies or brides or hunka “friend” ceremonies—featured beaded soles; they were not meant to touch the ground.5 In that sense, Sully’s understanding of the “Indian fashion”—an initiation of trade—missed the mark. As a prominent Dakota ethnographer observed, “Outside the family of birth, the tiyospaye, it was improper to give a present to a man. Yet now and then a young woman who fancied herself much in love secretly made elaborate moccasins or some male costume accessory and slipped it to the man of her choice.”6

In this Dakota context, the shoes and stockings and bare feet in Alfred Sully’s images appear as iconographic signifiers not merely of exchange but of some form of commitment—and, like the women, their footwear too seems suddenly to leap out of the images. The stockings, in particular, are both prominent and disorienting. They serve as evidence not of the oddity of Western goods mixed with Indian clothing (not actually odd at all) but of the possibility of a relationship conceived, at least on the Native side, through kinship politics and access to the power represented by the US military. And perhaps as something more, something that also carried emotional freight.

Alfred Sully, of course, could not have written of sexual alliance or emotional entanglement with an Indian woman in a letter to his parents. They had previously expressed their unhappiness about his marriage to Manuela de la Guerra and were likely anxious about the kinds of familiar frontier relationships Sully was representing in these paintings—close and affectionate exchanges with Indian women, known by name in two languages. Perhaps a mutual, unspoken awareness of this anxiety speaks to Sully’s effort to contain the situation through the distancing words of his letter. There, the women are more object than subject—artist’s models and nothing more.

Sull...