![]()

1

Origins of a Conflict

It was 1914 and the clouds of war were gathering over German South West Africa. Although the conflict that would play out in the protectorate was small given the scale of the Great War in Europe and elsewhere, it was key to the Allies’ African campaign and the history of the country that would eventually become Namibia. The participants included a small German colonial military force defending the territory against a much larger army fielded mainly by the Union of South Africa with some British and Rhodesian attachments. Indigenous peoples such as the Bastar, Herero, and Namaqua would also serve as guards, scouts, drovers, forced labor, and sometimes insurgents during the war. In the end, it was the South Africans who would benefit more from the use of indigenous support forces. The Germans, having quashed two recent revolts, had few armed indigenous troops in its service and feared arming or using any of the restive tribes in a conflict against fellow Europeans, primarily because the feared a resurgence of violence against their own people. Prior to World War I, the Germans believed the British were supporting rebels inside the protectorate, a belief they would carry over into the 1914-1915 conflict. The overall Allied victory in 1918 ended German colonial rule in Africa and brought about a new epoch in the history of what is now the country of Namibia.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, the territory of Deutsche Südwest-Afrika or German South West Africa (GSWA) was one of four German colonies on the African continent – the others being Togo, Cameroon, and Deutsche Ost-Afrika or German East Africa (GEA). Commercially administered by the German Colonial Society for South West Africa (Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft für Südwest-Afrika) since 1884, the Imperial German Government took full control of the protectorate in 1890. From that moment until the surrender of German forces in July 1915, the German Colonial Office administered the protectorate.

GSWA was the only one of the German colonies in Africa that was settled by a sizeable number of Germans. In 1914, the German population in the protectorate numbered about 12,000, while around 2,000 Boer-Afrikaners and less than 1,000 British civilians lived there. According to a rough census conducted in 1902, the indigenous population was about 200,000, but a large proportion, as many as 40,000 to 70,000 men, women, and children perished as a consequence of the fierce Herero and Namaqua (Hottentot) uprisings of 1904-1908.

That war between Britain and Germany would come was a theme that had dominated both private government and public discussion in the early 1900s. On a lesser level, the fear that a war would involve the Cape Colony (Union of South Africa from 1910) and German South West Africa was a subject that had concerned diplomats and military attachés since the Anglo-Boer War (also known as the Second Boer War of Independence or South African War). Mistrust was rampant on both sides of the border, although the Boer who lived in either country probably distrusted the British more. In Europe as well as the colonies, the Germans bristled over Edward VII’s Einkreisungspolitik – the isolation and containment of Germany by the Entente Powers, while Britain spoke of the Kaiser’s bellicose policies, especially Germany’s decision to build a navy that would compete with the Royal Navy’s dominance of the high seas, the construction of the Berlin-to-Baghdad railway, and two international crises over Morocco in 1905 and 1911.

GSWA 1914 (© James Stejskal)

While British leaders distrusted Germany’s global aspirations, the Union of South Africa government was worried about the intentions of its German neighbor. The ill-advised Kruger Telegram in which the Kaiser voiced his support for the Boer in 1896 should they go to war still resonated with leaders in London and Pretoria and made them suspect Germany’s territorial ambitions. German missionaries who lived inside Union territory were suspected of being spies and of attempting to mobilize the indigenous peoples to rise in rebellion. The threat of a German invasion of South Africa – real or imagined – was a topic that periodically came up in government circles as well as in the press. Conversely, the threat of war in Europe ensured the Germans in the protectorate maintained an equal distrust of their southern neighbor.

A small military force known as Die Kaiserlichen Schutztruppen (the Imperial Protection Force), along with an even smaller police force, Der Kaiserlichen Landespolizei, watched over internal security matters in the German protectorate, but being surrounded by Portuguese Angola to the north and by the Union of South Africa, Rhodesia, and Bechuanaland to the south and east, the Germans had few illusions as to the weakness of their position should war come. Additionally, Great Britain controlled the small Atlantic port enclave of Walvis Bay – known as Walfischbucht to the Germans – located just 35 kilometers south of the inadequate German port of Swakopmund and roughly centered on GSWA’s long coastline. Walvis had an excellent harbor and would serve the Allies well during the campaign.

Both the protectorate Governor Dr Theodor von Seitz and the Schutztruppe commander, Lieutenant Colonel Joachim von Heydebreck assessed that Britain would use South African forces to attack the protectorate if and when war was declared – despite Berlin’s trust in the 1885 General Act of the Conference of Berlin. This act, commonly called the “Treaty of Berlin”, stated that in the case of war between signatories, territories belonging to the belligerents would be considered neutral and would refrain from “carrying on hostilities in the neutralized territories and from using them as a base for warlike operations”. As a consequence, the German Foreign Office thought, or perhaps hoped, its territories would be immune to the coming war. The treaty stated clearly, however, that it was applicable only to the territories comprising the Congo River Basin and, therefore, did not apply to other colonies in Africa like GSWA, Togo, or Cameroon. The German assumption was wrong and Berlin’s refusal to understand this fact left Governor von Seitz with very limited resources with which to defend the territory. Von Seitz and his commander were to secure the huge territory with a largely hostile, indigenous population and prepare for a possible invasion by an external enemy, missions that the Germans were not prepared to carry out without reinforcements from the fatherland. Von Seitz had consulted in detail with Heydebreck and previous commanders about the available options as they watched the threat of war with England grow. As a result, von Seitz – although failing to obtain approval for an increase in the Schutztruppe – did secure passage of a new defense law in 1913 that gave him extensive powers in the event of an emergency. In the spring of 1914, von Seitz began to put the law into effect. This included the emergency call-up of all reservists, home defense militia, and those furloughed from active service. He was also authorized to engage volunteers and recall retired officers to duty.

Lieutenant Colonel von Heydebreck and the Schutztruppe staff riding through veld during maneuvers in August 1914. (© Namibian National Archives)

Shortly after the declaration of war in August 1914, South African Prime Minister Louis Botha cabled London and stated that the Union Defense Force (UDF) was capable of independently defending South African territory from German aggression and suggested the British forces stationed there might be withdrawn for service in Europe. The British government quickly accepted the offer on 6 August 1914, but requested the government of South Africa consider undertaking “a great and urgent Imperial service” by seizing GSWA’s port cities of Swakopmund and Luderitzbucht (Luderitz Bay) and the wireless stations there and in the interior at Windhoek. On 10 August 1914, after consulting with his close colleagues, Botha decided to take on the task and quietly began preparations to mobilize the army for war, a decision that would have serious consequences in the coming months.

Generals Botha and Smuts during the First World War. (South African Government Photo – released into Public Domain)

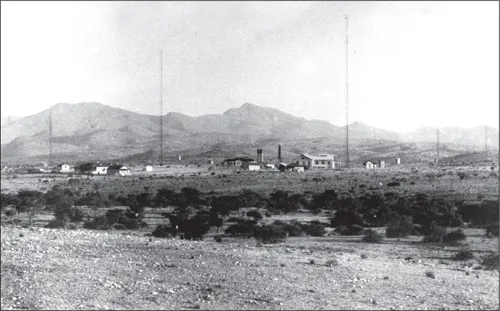

Telefunken Radio Station Windhoek, masts and buildings, 1914. (© Namibian National Archives)

The Union Army, along with elements from Britain and British Rhodesia, would launch a campaign to capture the German protectorate with the aim of neutralizing the ports and, more importantly, destroy the large wireless station in Windhoek that was crucially important for German naval raiders and commercial shipping. At the time, the German wireless stations at Kamina, Togo and Windhoek were second only to the Telefunken site at Nauen, Germany, the largest in the world, and all were crucial communication components for the German Imperial Navy and its commercial maritime enterprise.

There were opponents to Botha’s course of action; primarily the Boers who had only recently fought against the British Empire in their failed wars of independence. Many of them had taken Boer General Louis Botha at his word when in 1901 he said of the peace agreement with England:

It is better now to make peace and save what there is to save, before the entire nation is in a concentration camp or murdered by the indigenous peoples. We can take up arms again when Britain is in difficulty and then win our lost freedom.

By 1914, however, Botha’s position towards England had softened, while that of many of his countrymen had not. Coupled with internal political bickering over labor issues, this dispute led to a deepening of the schism between those who wanted to support England and those who wanted to rebel. Botha and his close ally and Defense Minister General Jan Christiaan Smuts were on one side; the “old Boers”, General J.B.M. Hertzog, Nicolaas de Wet, and former Orange Free State President Martinus Steyn were on the other. Hertzog’s National Party opposed Botha’s plan and General J.H. del la Rey, following the South African Parliament’s 15 September 1914 vote to invade German South West Africa, called the Boer peoples into open rebellion against the government. While much of the UDF was fixed on the border with the Germans, the internal revolt would initially occupy Botha inside South Africa. Botha decided to use loyal Boer troops to fight the Boer rebels. In the end, the Boer uprising was little more than a temporary inconvenience for Botha. Luckily for the government, the majority of the Boers had already reconciled themselves to living within the British Empire.