![]()

CHAPTER ONE

This bed is my reward after three long days of driving. My body is stiff and aches with exhaustion. When I collapsed here, I was sure the bed would swallow me and I’d sleep for days, but the groaning springs, the mattress that smells of stale rust, and my own creeping anxiety won’t let me settle. If I’m being honest, it’s probably just the anxiety.

The Goode Night Inn sits on the edge of Pennington in northeastern Nova Scotia. It’s a motel for tourists: better people from better places who find musty mattresses quaint and charming. Every surface in the room is covered with lighthouses and mayflower patterns and decorative shells. There’s a coffee table made from an old lobster trap. Being here makes my chest tight, East Coast kitsch fuelling my panic.

I remember the people who own this place, or rather, I remember their son, Mark. Four years older than me, Mark Goode was leaving junior high as I arrived, and it was the same in high school. Talented, handsome, and popular, Mark never seemed like a real person. He was a Class President 1992 photo in our high school’s front hall and a name filling trophies in the glass case at the rink. Mark was captain of the Pennington Royals back when I believed playing for the Royals was all anyone could hope to achieve in life. Where had Mark Goode ended up? Wherever he is, I’m sure he has success and money and a pretty wife with whom he’s made a dozen pretty babies. How could someone like him not?

The motel ceiling is dirty, but even the dirt feels quaint. I can’t say for sure how long I’ve been staring at it. This is not where I belong. In fact, cutting out war zones and leper colonies and the really cold parts of Manitoba, this is the last place in the world I want to be. Pennington is a rot. It’s a stink that sticks to you like smoke from a campfire. It’s a glue trap; to escape means chewing off your own limbs.

I might be exaggerating, but only a little. I’m in the throes of an existential crisis, which can bring on certain failures of perspective.

“How long will you be staying with us?” Mrs. Goode asked me from behind the counter in the motel office when I checked in.

“I don’t know. A week?” Would I really be here for a week? Maybe more. Probably more. Indefinitely? Fuck.

Mrs. Goode raised her eyebrows when she read the name on my credit card, then furrowed them as she tried to solve the puzzle of my family tree. Lineage matters around here. She knew my stock was Macallister, though not which sort of Macallister.

“You’re Vivian’s boy.”

Rats. Besides my father’s name, I also have my mother’s eyes.

“Yes.”

“Your mother and I used to run around together,” Mrs. Goode said, holding her hands over her heart. “She was a lovely woman.”

I pulled my lips back in a way that wasn’t wholly a smile, head down, eyes up, like a four-year-old who’s shit his pants and isn’t sure if he’s in trouble or not. Mrs. Goode, showing incredible kindness, let me off easy by handing over my room key without more discussion.

Pennington is a small town the way all towns in Nova Scotia are small. In the summer, it smells like salt, and in the winter it snows that wet, heavy Maritime snow—heart-attack snow, they call it. Everybody knows of everybody else and their business. The same guy has been mayor for thirty years and will be until he doesn’t want it or, more likely, he drops dead, at which time his son will probably take over. It’s a town that thrives on routine and expectation and neighbourly kindness. There are hundreds of towns just like this—Pennington, Pugwash, Tatamagouche, Antigonish, Pictou. The specifics don’t matter.

I need a drink. Maybe two. The Goode Night Inn doesn’t keep a stocked mini-bar. It feels late—in a Nova Scotia November, the sun sets shortly after lunch and doesn’t come up again until May—but my watch says it’s not quite nine o’clock. Actually, it says it’s not quite six o’clock because I haven’t spun it forward from Calgary time yet. I definitely need a drink. Probably two. It’s the only thing that will keep me from getting back into my truck and driving three more days to, well, anywhere else. I have nowhere to be, but I also can’t sit here anymore marinating in my own overwrought tension.

I dial the number to Sunshine Cabs from memory, surprising myself after all these years. Sunshine is two cars driven in shifts by a handful of guys, one of whom arrives in front of the motel in an old Monte Carlo about five minutes after I call. The cab’s interior reeks, a combination of the cigarette the driver is smoking now and the two hundred thousand that came before it. There’s no meter, Sunshine Cabs use a flat fee: five dollars inside town limits, seven to the rural roads.

“Where to?” the driver asks.

“A bar,” I say. “Pat’s Pub, I guess.”

He looks at me through the rear-view mirror. “Pub closes at nine on Wednesdays.”

Shit. “Are there any bars open?”

He considers my question for a second. “I s’pose J.J.’s will do ya.”

I’ve never heard of it, so it must have opened in the last ten years. “Sure, take me there.”

He pulls out of the lot of the Goode Night Inn and, four and a half minutes later, into the lot of the Pennington Recreation Centre. The rec centre, as its name hints, isn’t a bar. I spent a lot of time here as a kid and, from the outside, the building doesn’t seem to have changed at all. I make no effort to either pay or get out of the cab, and the driver eventually turns in his seat to look at me. Time and experience and smoke have weathered his face. I can tell this is a man who knows things—life lessons learned first-hand through circumstance and questionable decisions. I am in need of sage words of comfort and direction. He takes a long pull on his cigarette, the cherry glowing in dark silence.

“Bar’s upstairs. Five bucks.”

As sage words go, they’re a bit lacking in comfort, but at least the direction is clear.

•

Built in the mid-1980s, the Pennington Rec Centre houses the local hockey rink, a small canteen, and eight lanes of five-pin bowling. The rink, Macallister Stadium, seats about four thousand, a little less than half the population of the entire town, and used to be filled for each of the twenty-eight home games the Pennington Royals play each season. The bowling alley, on the other hand, was used almost exclusively by Rotary Club members and kids’ birthday parties, and, truth be told, not even very many of those.

Since I was last here, the guts of the building have been renovated: the floor in the lobby upgraded from brown tile to blue tile, the old trophy case replaced with a newer, bigger trophy case. The box office—a small booth in the middle of the room—is dark and empty. About ten feet behind it, the double doors that lead into the rink are closed, though I can hear the echo of pucks banging off boards from inside, likely from a practising team or beer-league game, at this time of night. The biggest wall in the lobby has an old mural of hockey players—kids and seniors, some wearing old brown gear, others with more modern stuff. I think it’s supposed to represent hockey through the years or community spirit or whatever, but the guy who painted it was bad at faces so all the adults look like sad tropical birds, the kids like deranged cherubs. The only goalie in the image, standing to the far side of the wall, has had half his body covered with a large vinyl sign. Blocky red letters spell out “J.J.’s Sports Bar” and “Five Dollar Jugs Before Every Home Game.” There’s an arrow pointing to a dark staircase tucked around the corner.

Up the stairs and through a door, I find the bar. The space used to be a Legion-sponsored room where veterans could smoke cigars and watch hockey through a bank of windows looking out onto the ice, above the scoreboard at the visitors’ end. Add a bar, some tables and chairs, stick a pool table in the corner, and presto—a perfectly acceptable drinking establishment is born.

It isn’t busy in here. There’s just me, the bartender, two old guys watching sports highlights on the TV behind the bar, and a guy in a Leafs toque shooting pool by himself.

I want to order a gin and tonic, but I’m worried I’ll be judged. This is rum country. Rye for special occasions. I ask for a rum and Coke and let the bartender know to keep them coming, which is unnecessary; drinking with purpose is the Pennington default. The old men, one hidden behind a bushy beard, the other behind a swollen red nose, look me over with mild curiosity. I offer a stiff, deliberate nod. They aren’t impressed and turn their attention back to the TV. Fair enough. I am, if nothing else, unimpressive.

During the first drink, the glass shakes in my hand.

During the second, I’m able to relax my neck and shoulders, tense from driving and stress and twenty-eight years of bad posture.

During the third drink, I take stock of my situation. Everything I own is wedged into the back of my 1993 Dodge Ramcharger sitting outside the Goode Night Inn. I haven’t showered in three days because I’ve been driving and sleeping in the truck. My brown hair is dark with grease and pressed flat under a frayed Flames ball cap. I haven’t changed my clothes since leaving Calgary because, with a stunning lack of foresight, I buried them in a suitcase under a large flat-screen TV, a pretty decent stereo, one box of books, two boxes of CDs, and two miscellaneous boxes marked “STUFF,” and couldn’t be bothered to dig them out along the way. Now I’m drinking in Pennington, Nova Scotia, the place I was raised and the place I left without fanfare as soon as I could. My bank account is worth about $300 and my credit card, now being charged $49 a night by the Goode family, has limited runway. I think that’s about it.

During the fourth drink, I wallow in a deep and profound melancholy, questioning every choice I’ve ever made and throwing blame anywhere I think it might stick.

On the fifth drink, I am recognized.

“Macallister?”

Shit.

“Hey, Macallister!”

Turning on my stool, I meet the eyes that belong to the head that belongs to the pool-playing Leafs toque. Paulie Coleman. He’s older and quite a bit heavier, but it’s definitely him.

“Paul. Paulie. Hi,” I say, without smiling.

“Hey, man. Wow. Adam fucking Macallister. Long time,” he says with enough smile for both of us.

I haven’t thought about Paulie in a decade, but suddenly remember everything about him. Nice guy, kind of dim, enthusiastic without discrimination. He has apple cheeks and everything he says is too loud by half. When we played peewee hockey, he took a wild swing at a flying puck and clipped a kid on the other team. The kid went down like, well, like someone had just tried to decapitate him with a hockey stick. Paulie got suspended for six games, though if you asked him, it was a bullshit call. “I was going for the puck,” he’d cried. “How is that against the rules?” He didn’t make a lot of time for nuance.

“Yeah, it’s been a while,” I say.

“Yeah, man, like forever.” He rubs his forehead with his wrist, pushing his toque askew. “So, what have you been up to?”

It’s a vague and open-ended question, considering he hasn’t seen me in ten years. If anyone else had asked it, I’d assume they were making polite conversation. But Paulie oozes earnestness. He’s genuinely curious and, for reasons that have more to do with the rum than a burning desire to play catch-up, we grab some stools overlooking the ice and we talk. We talk and we drink. We drink a lot, actually, and the more I drink, the more I offer details of my life—a careful selection of the places I’ve been and things I’ve done that might impress a guy like Paulie. I dial everything up about thirty percent because why the hell not, and when I get to the part about being a sports reporter in Calgary, I build myself up like I’m the second coming of Ring Lardner.

“And you’re just here for a visit?” he asks, nonplussed by everything I’ve just said.

“I guess I’m sort of working. I’m only here for a week, but it’s not a vacation or anything.” This is sort of true.

“Oh yeah? What do you mean?” he asks.

“It’s just this thing I’m writing about my dad.” Not strictly untrue. “It’s a feature for Sports Illustrated.” Now I’m mostly lying. “You know, the way he played hockey and how people remember him, but really it’s about how hockey’s violent culture fits into today’s society.” I made that part up just now. “And it’s about redemption.” Oh god, stop talking already.

“What about you,” I ask, trying to shift the onus onto him. “What have you been up to?”

“Oh, you know, nothing really,” he says, scratching the inside of his ear with his pinky finger. “Just caught in the comfort zone. I do some roadwork in the summer, get my pogey in the winter. Live lean when it runs out.” He’s still living with his parents, a fact he offers without excuse or embarrassment. It’s the simple truth of Paulie.

The game on the ice below us ends with a long whistle from the referee, and the players—men between thirty and sixty years old, senior leaguers who have been playing against each other in various combinations for decades—make their way off. A couple stay behind shooting pucks into the empty net, squeezing in a few more minutes of ice time.

And then I see him. My father. He’s pulling the large doors at the far end of the ice and propping them open, before disappearing back into the Zamboni room. He doesn’t look up because he has no idea I’m only two hundred feet away.

“I didn’t think he’d be here this late,” I say.

Paulie squints at the ice to see what I’m looking at. “Your old man? He’s always here. I assumed you were staying next door with him.”

“Next door? Dad’s not on Duke Street anymore?” Are there even houses next door to the rink? There didn’t used to be.

“He’s just down the hall there,” Paulie says, gesturing toward the door.

“Down the hall?”

“Yeah, man.” Paulie looks at the door quizzically, taking a second to confirm this fact to himself. “Like ten feet down the hall,” he says, as though it was the details of the hall itself eluding me.

Below us, the Zamboni pulls out onto the ice, my father at the wheel.

“When did that happen?”

“I dunno, a few years ago. You said all that stuff about Sports Illustrated or whatever, I figured you’d talked to him.”

“No,” I say, trying to remember when I last spoke to my father on the phone. A few years ago, probably on my birthday or Christmas or something, seems about right. “Not yet.”

“Last call, guys,” the bartender calls out behind us. I’ve never needed another drink so much.

•

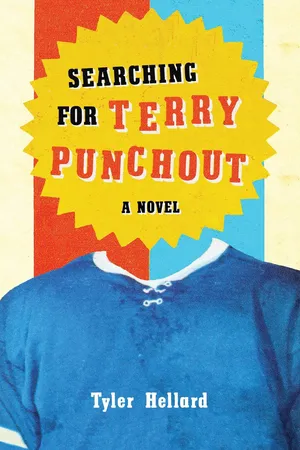

Terrance James Macallister was born on a farm just outside Pennington in 1947, the son of sheep farmer Ellis Macallister and his wife, Agnes.

Terry learned to skate on a pond behind the barn when he was five years old, but didn’t start playing organized hockey until he was thirteen. The years of pond skating and farm chores paid off and Terry became a local star overnight, powering through the other kids and scoring almost at will. To compensate, they made him play with the older children, and at just fifteen he joined the Pennington Royals, a junior team of seventeen- and eighteen-year-olds. He scored fifty-four goals, a record at the time.

After Terry had been with the Royals for a year, a man showed up at the farm and offered him a chance to play for the Toronto Marlboros in the Ontario Hockey Association. Terry wasn’t as successful against the bigger, faster, and more skilled players in the OHA, but he worked hard and carved out a role, using his farm-boy strength to beat up players whenever his coach asked him to, which ended up being fairly often. Beating people up on the ice would become Terry’s calling in life, and his ability to intimidate pretty much everyone else in the league helped the Marlies win a lot of hockey games. Over a three-game stretch in the playoffs during his first year with the team, Terry had three different one-punch knockouts, and while records aren’t kept on such things, no one could remember seeing anything like it before. A reporter for the Toronto Telegram dubbed him Terry Punchout and the name stuck.

Terry wasn’t drafted by an NHL team, but he got an invitation to the Toronto Maple Leafs training camp when he was nineteen. During his first scrimmage, he beat the holy hell out of the Leafs’ long-standing tough guy, George “Duck” Wilkins, making a good impression on all the people on whom you want to make good impressions. A week later, Duck was traded to St. Louis and, on October 14, 1967, Terry Punchout made his professional hockey debut. He would go on to play 1,032 regular season games over the next fifteen years. He scored 119 goals and added 301 assists. By any statistical standard, it was a bad hockey career, but Terry also accumulated 3,994 penalty minutes, more than any player before or since. It’s a dubious record, not the sort of thing that would put him in the Hall of Fame, but it made him a legend, nonetheless. There isn’t a hockey fan alive who doesn’t know his name. His hometown named a stadium after him.

I know all this about Terry Punchout because I know everything about Terry Punchout. I have every stat and every milestone memorized, and I know a few things that aren’t in the record books. His favourite colour is green. He’s allergic to rabbits. He likes to drink rum and Coke in a tall glass with lots of ice.

What I didn’t know is that he now lives in the same rink they named after him, the same rink where he’s been driving the Zamboni since I was fifteen years old.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

I need to piss so bad it hurts, but I’m afraid to open my eyes. The problem with rum is the hangover. It isn’t like other hangovers; it gets inside every part of you. I can feel it in my hair. Paulie and I had already had more than enough to drink when the bartender shut us down. Still, we convinced him to sell us a bottle of dark rum for sixty bucks, which I’m fairly sure came from my wallet, and we opened it in the parking lot.

I lift my eyelid just a sliver and blinding, unimaginable light pours into my skull. My stomach lurches. It takes several hard blinks for the room around me to slowly take shape. Flowery wallpaper. Bay windows. Fake plants. I’m on a large grey couch with thick, soft cushions, my long body stiff from bending while I slept. On the coffee table in front of the couch is a tall glass of water resting on a small white doily. Beside the glass is a bottle of Extra Strength Tylenol. Beside that is a bowl of potpourri. The rich, lavender scent only makes me feel worse. I take a deep breath and lift myself up on my left side, nice and slow. The childproof cap on the pill bottle is a struggle, but I manage to spill four tablets into my hand. I try to choke them dry for fear of adding more water to my already taxed bladder, but there’s not enough spit and the pills turn into a bitter paste on my tongue. I gag a little and grab the glass. A sip turns into a mouthful. The water is tepid, but I’m a sponge, and empty it in three swallows. I figure I’ve got about two minutes to find a toilet.

Steeling myself, I stand in one jerky motion. The room tilts impossibly, and while the rational part of me understands this is the hangover challenging my senses, there is another part of me that is surprised furniture isn’t crashing into the wall. I take a beat to let the room level itself, which is when I notice I’m not wearing clothes.

It is at this precise moment, leaning hard to my right in just my boxer shorts, that my grade-school music teacher walks into the room.

“Oh, good, you’re up,” she says, ignoring nearly everything that’s happening in front of her. “I just woke Paul for breakfast. I hope you don’t mind, but I threw your clothes in the wash with his. They seemed a bit grubby. Are you hungry?”

There are a lot of things I want to do right now—cover myself up, apologize profusely, throw up, die a quick death—but there is one very pressing matter to deal with first.

“Can I use your washroom?”

“Sure,” she says, “it’s upstairs. The one with the toilet.”

While pissing, I remember making Paulie sit and drink with me on a concrete slab in the rec centre parking lot so I could see my father again, though I didn’t say that out loud. And sure enough, after about thirty minutes—after the beer-league players and old guys from the bar and even the bartender had cleared out—my father came to the front door to lock up the building. He did it from the inside, then disappeared back into the darkness of the lobby like Pennington’s Quasimodo. It was hard enough coming back here knowing I needed something from him, that I needed him. I’d promised myself I’d get through this without ch...