- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

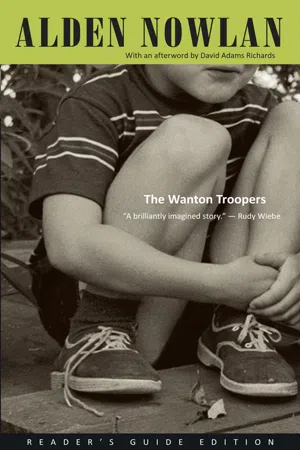

The Wanton Troopers

About this book

In this new edition of Alden Nowlan's poignant first novel, published posthumously in 1988, a boy growing up in a small Nova Scotia mill town is abandoned by the young mother he adores. Family relationships, sexual confusions, and the pains of love are rendered with deep and authentic feeling. This is an essential book for all readers who have admired the work of this major Canadian writer.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

An Interview with Alden Nowlan

JON PEDERSEN

For three days in 1982, I interviewed Alden Nowlan for the National Film Board of Canada film production Alden Nowlan: An Introduction. The resulting half-hour film was completed in 1983, after Nowlan’s death. The complete interview consists of approximately five hours of synchronized 16mm film shot by Kent Nason and full-track ¼" audiotape recorded by Art McKay, both of the National Film Board, Atlantic Region.

The following includes about half of the interview; a transcript of the complete interview is available from the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick or the Harriet Irving Library, University of New Brunswick.

Jon Pedersen

All writers complain of the constraints and difficulties under which they work. Is it a painful and difficult process for you?

Alden Nowlan

Well, writing with me is almost an inevitable process. I’m a writer almost in the same sense that I have grey eyes. I would write poems even if no one read them, but I wouldn’t write stories or plays or newspaper columns if no one read them, obviously. But I would be writing poems even if nobody read them.

JP Is Fredericton a good environment for poets? Is poetry taken seriously?

AN I suspect it is, but it really wouldn’t have made a great deal of difference to me where I was, as long as the place where I was wasn’t actively uncomfortable, so long as I wasn’t in a situation which was painful or humiliating. I mean, I’m not really an active enough participant in the community of Fredericton, in a sense, that it makes any great difference to me that I live here, you see. I mean, partly because of my background, I’m not the sort of writer who needs to be associated with other writers in order to be creative.

JP Could you elaborate on that?

AN Well, I grew up utterly alone in many ways. During my adolescence, I was so alone I might almost as well have been on a desert island. In fact I would have been happier on a desert island because then there would have been no one to torment me. And so I’m really a very self-sufficient person. I never mind, really, being alone.

JP Do you and your wife go out much?

AN I don’t know, really, what’s very much or what’s little. It’s all relative, isn’t it?

JP What’s the room like where you work?

AN A mess.

JP Do you have a window in it? Do you need absolute silence?

AN I read somewhere once that Alice Munro (whom I think is perhaps the best short story writer in the country) has said she couldn’t write in a house in which there was another adult, and I’m very much like that. I couldn’t really write anything, except for a newspaper column, when we have house guests or that sort of thing. Writing is a very private thing to me in the sense that if I were working on a poem and someone came into the room, I would automatically cover it with my hand, just as a reflex gesture.

JP And yet you can go on and publish that for the world to see?

AN Yes, but it’s sort of like having a child in the womb and having it born. At one moment it’s a very private part of the woman, in a sense, and then suddenly it has a life of its own.

JP When you first began to write things, why and to whom did you write them?

AN The very first things I wrote were attempts at Biblical revelations because I thought I was going to be a prophet. Then I started writing poems which I thought were enormously good. I mean, I thought I was intensely precocious, but looking back, the sort of things I wrote when I was eleven and twelve were the sort of things that anyone eleven or twelve could have written if they’d wanted to do it.

JP How successful are you at saying what you want?

AN Well, I agree with Paul Verlaine, who said that “no poem is ever finished. At best it’s always abandoned.” You never really say what you want to say.

JP Do you often feel frustration or disappointment?

AN Momentarily, but it’s not prolonged because I think you have to make peace with your own limitations, actually.

JP How do you feel about criticism? Have you found professional criticism helpful or a hindrance?

AN The criticism in this country . . . First of all, I think the gift of being a genuinely fine critic is probably rarer than the gift of being a genuinely fine creative writer. But as it is, criticism can be done by anyone who wants to do it, and I think that the standards in this country have actually deteriorated since I’ve begun to write. When I started to publish things, my first little sixteen-page chapbook of poems, for instance, was reviewed by Northrop Frye, among other people. And now, you would be more apt to find a book by Northrop Frye being reviewed by some seventeen-year-old in the slow learners’ class in Moose Jaw. That sort of thing has changed. Of course, many, if not most, of the book reviewers don’t read the books anyway and generally just look at the jacket and flip it open and look at two or three pages. Also, in this country, where the reviewers and the poets and the fiction writers all tend to be the same people, obviously you get a lot of the business of “You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours,” you know, and you even get people attacking your book because a friend of yours attacked a book of theirs, you see.

JP Have you ever been tempted to strike out at your critics?

AN I used to, but it’s a loser’s game. I probably would strike out at them if I could do it with the style of Irving Layton. I have one thought that has entered my mind, though, just recently. I’ve always felt that I could write a good horror novel, like Stephen King’s. I had this wonderful fantasy recently of writing a horror novel which would become a bestseller and be made into a movie similar to The Shining, with Jack Nicholson, and make me an enormous amount of money. And I would buy a helicopter and I would fly from one end of Canada to the other, and I’d particularly stop for an afternoon in Toronto, and I would piss from my helicopter on every book reviewer in the country!

JP You told me last week you did something you’ve always wanted to do.

AN Last week I did a thing which I’ve been trying to will myself into doing for years. I received a fat envelope of clipping service reviews of my last book from Clarke Irwin, and I took out the reviews without reading any of them and threw them into a filing cabinet. Because the thing about it is, the good ones only make you feel good for about half an hour, whereas the bad ones, no matter how stupid they are, can make you feel bad all day. Because we’re all so vulnerable that even if you know the person who wrote the review is, first of all, an idiot, and secondly, he didn’t read the book at all, there’s sort of a little voice inside you telling you you’re probably as bad as he says you are. And even if you don’t have that little voice, it’s so frustrating because you can’t retaliate. There’s no way you can punch him in the mouth. There’s no way you can answer him, really.

JP So being an artist — a poet — is really a very vulnerable place to sit.

AN It’s often occurred to me how interesting it would be if people in other fields of endeavour were subjected to the same sort of public criticism that artists are. For instance, if you took a medical doctor and on Friday there was a review that said Dr. Smith’s bedside manner leaves much to be desired and his knowledge of drugs is certainly not up to date, and as for his operating technique — it’s a complete fiasco, and anybody who deals with him is in mortal danger of losing his life. Or if you reviewed the works of policemen, you know, and said, “In this investigation Sergeant Jones showed the utter incompetence to which his observers have now become accustomed.” That is the sort of thing an actor or painter or writer — any sort of artist — has to cope with constantly. Politicians deal with all sorts of criticisms too, but the thing they do is not so private — it doesn’t make them so vulnerable.

JP What sort of influence have you had on other writers?

AN That’s a very difficult thing to assess. That would be something that’s more for them to say than for me to say. I think one influence I could say that I’ve had is the influence of simply having been here. You see, when I started to write and publish things, there really was nobody else at all writing in New Brunswick and not many in other parts of the Maritimes, and so I think that I might conceivably have been an influence in that. You take a brilliant young New Brunswick-based novelist such as David Adams Richards, and I think there may well have been an influence on him, say, when he was in high school and starting to write, simply by seeing one of my books in the high school library and thinking, “Gosh, you can live in New Brunswick and you can write about New Brunswick,” you know.

JP Do you keep a sort of abstract reader in mind when you write?

AN Yes, I suppose I do, because in a sense when I began to write poems, I was addressing them . . . Well, I did it partly for the same reason some other lonely children invent an imaginary playmate, and so I suppose in a way I address them all to some imaginary playmate — a kind of a sympathetic listener. And the best thing is when, through personal contacts — meetings with strangers or letters from people — I discover that someone has gotten the message. It’s like putting a note in a bottle and throwing it into the ocean and it floats across and someone tells you they’ve received it.

JP So your poems, then — it’s fair to say they always have a message or something specific ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Notes to the First Edition

- Notes to the Second Edition

- One

- Two

- Three

- Four

- Five

- Six

- Seven

- Eight

- Nine

- Ten

- Eleven

- Twelve

- Thirteen

- Fourteen

- Fifteen

- Sixteen

- Seventeen

- Eighteen

- Nineteen

- Twenty

- Twenty-One

- Twenty-Two

- Twenty-Three

- Twenty-Four

- Twenty-Five

- Twenty-Six

- Twenty-Seven

- Twenty-Eight

- Twenty-Nine

- Thirty

- Afterword

- About the Author

- An Interview with Alden Nowlan

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Wanton Troopers by Alden Nowlan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.