![]()

Chapter One

Establishing the Route:

The Beginnings to 1760

“I sent a letter to Count Frontenac by a canoe which was going to Quebec.”

— Joseph Robineau de Villebon, governor of Acadia, Fort Nashwaak, September 20, 1698

The story of the Grand Communications Route begins with the end of the last ice age. When the first people arrived in what is now New Brunswick, between 6,000 and 10,000 years ago, they found a system of interlocking rivers that was marvellously suited for transportation. The central feature was the St. John River. Rising in northern Maine, the St. John flows approximately 725 kilometres to the Bay of Fundy, with few obstacles. The first, the Reversing Falls at the mouth of the river, could be negotiated at high tide or bypassed using a portage. While there were rapids at Meductic (now flooded), the only other impediment was at Grand Falls. Here, the St. John River plunges twenty-three metres and then rushes through a two-kilometre gorge. This obstruction could be bypassed only by a portage. Then, once the rapids at the mouth of the Madawaska River at Edmundston (or Little Falls) were passed, the way was clear up the Madawaska to Lake Temiscouata. From there, two series of rivers and small lakes led to Trois Pistoles on the St. Lawrence River. Later, a portage road was cut from Cabano to give a more direct route to St. André and later to Rivière-du-Loup. All told, the route from Rivière-du-Loup to Saint John was approximately 515 kilometres, about 435 kilometres of which were by water.

In addition to providing a route from the south shore of the St. Lawrence River to the Bay of Fundy, the St. John River system has a number of branches that give access to the whole area. North of Grand Falls, the Grand River-Wagan portage route led to the Restigouche River and the Bay of Chaleur. Below Woodstock, at Meductic, an important portage route led west to the Eel River and, by a series of portages, to the Passamaquoddy, Penobscot and Machias rivers in Maine. At Oromocto, a route along the Oromocto and Magaquadavic rivers gave access to the St. Croix and rivers in Maine. A little further downstream, the Lake Washademoak-Canaan River-Petitcodiac River route led to Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

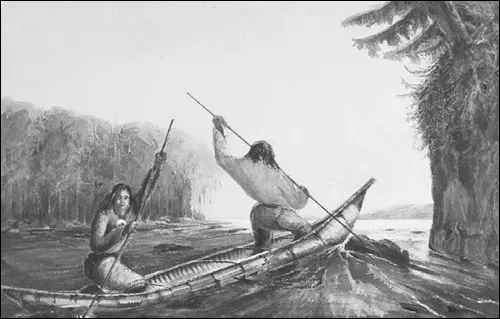

The Natives of the region developed birch bark canoes about 3,000 years ago. These craft weighed only about forty-five kilograms and could carry four adults. Capable of being paddled or poled and easily carried over portages, they were ideally suited for their function. With their canoes and river systems, the first people of New Brunswick had a transportation network that was the equal of modern roads.

When French explorers arrived in the early seventeenth century, four main groups of Native people lived along this system. All were of Algonquin stock and appear to have arrived in two distinct migrations from the west. The first were the Mi’kmaq, who lived in eastern New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. It is thought that they arrived via the St. Lawrence River and the Gaspé, but parts of the Grand Communications Route may have been on their migration path. Later, the related Maliseet, Passamaquoddy and Penobscot peoples moved in from the southwest. Their tribal boundaries were well defined by the river watersheds, with the Maliseet living along the St. John River, the Passamaquoddy around Passamaquoddy Bay and the St. Croix River, and the Penobscot further south in the area of the Penobscot River in Maine.

Archaeological evidence shows that the Grand Communications Route was used for trade, hunting, fishing and war. Maliseet and Mi’kmaq legends testify to a history of warfare, but, while the First Nations of New Brunswick were fierce warriors, they do not appear to have fought amongst themselves. The common enemy of both the Maliseet and the Mi’kmaq were the Mohawk, who lived at that time along the St. Lawrence River in the area of Quebec City and Montreal, although they later withdrew into what is now upstate New York. Mohawk war parties came down the route from the north, while Maliseet and Mi’kmaq war parties travelled up it. Perhaps the best known war story tells of Malabeam, who saved her people from a Mohawk war party by luring them to their deaths over the waterfall Checanekepeag — the Destroying Giant — at Grand Falls.

Micmac Indians Poling a Canoe Up a Rapid, Oromocto Lake, New Brunswick (1835-1846), by Richard Levinge. The birch bark canoe, developed about 3,000 years ago, enabled Native people to travel easily over the interlocking systems of lakes, rivers and portages in what is now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Maine. NAC R9266-302

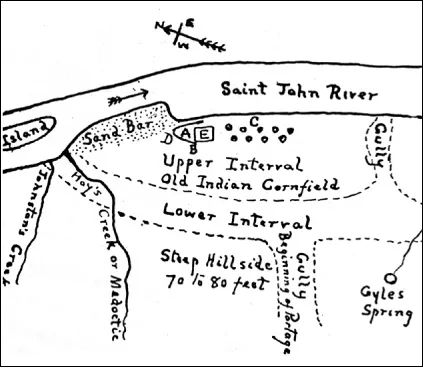

Fear of the Mohawk led the Abenaki to build the first known fortifications along the Grand Communications Route at Edmundston; another fort was at the important Maliseet village of Meductic, and indications suggest that there was one at Aucpac, on Hartts Island, above Fredericton. Along the lower river, forts were located at the mouth of the Nerepis River and on Navy Island, which is now under a pier of the St. John Harbour Bridge. The Mi’kmaq had forts at Richibucto and at Old Mission Point near the mouth of the Restigouche River. These defensive forts, which offered shelter to the local inhabitants when threatened by attack, were simply built but effective. Dr. W.F. Ganong describes the one at Meductic as having a central cabin surrounded by a ditch and parapet that was topped with a palisade. The fear of attackers must have been strong, for the Maliseet had only stone tools with which to dig the ditch and to cut and shape the trees for the stockade. Mohawk raids into the St. John valley continued until the 1660s.

The Maliseet fort at Meductic. A: council place; B: church site; C: camping place with wigwams; D: fort site; E: graveyard. “Beginning of portage” is the head of the Eel River portage route to the Penobscot River system in what is now Maine. The site was inundated by the Mactaquac headpond in 1967. W.O. RAYMOND, THE RIVER ST. JOHN

The established patterns of life began to change in New Brunswick in the early seventeenth century. On June 24, 1604, the feast day of Saint John, a French exploring party led by Sieur Pierre Du Gua de Monts entered the Saint John harbour. Their arrival marked the start of the French colony of Acadia, which would last until 1755. Unlike the British colonial period that followed, the first hundred and fifty years of European occupation were rough and tumble, characterized by almost constant fighting. Ownership of Acadia changed hands several times, and as it changed, so did the importance of the Grand Communications Route.

After a disastrous winter on St. Croix Island, de Monts moved his settlement to Port-Royal in the Annapolis Basin. This colony, in what is now Nova Scotia, struggled on until 1613, when Captain Samuel Argall of Virginia destroyed it. In 1621, James I of Britain gave Sir William Alexander a grant that included peninsular Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, which he named Alexandria. As part of his plan to colonize the region, he sold baronetcies to Scottish gentry for £1,350. This settlement scheme faltered, and when the Treaty of St. Germain returned Acadia to France in 1632, the Sieur Isaac de Razilly led the first group of new colonists to the area.

Acadia was really a business venture of the Company of New France, similar to the Company of One Hundred Associates that controlled the colony at Quebec. Both companies were under the influence of Cardinal Richelieu. When de Razilly died in 1635, his authority as lieutenant-governor in Acadia passed to Sieur Charles de Menou d’Aulnay, who had accompanied him from France. Sieur Charles de Saint-Etienne de La Tour contested this transfer of power. Remaining in Acadia after Argall’s conquest, he, too, had been named lieutenant-governor of Acadia. D’Aulnay’s grants included the rich fur-producing area of the St. John River valley, at the mouth of which La Tour had built his fort. At the same time, La Tour’s grant included Port-Royal, where d’Aulnay had his base. D’Aulnay and La Tour became bitter rivals, and a period of Acadian civil war ensued. The rivalry ended in 1645, when d’Aulnay captured Fort La Tour, hanged the garrison, destroyed the fort itself and built a new fort on the west side of the harbour, which he named Fort Charnissay. When d’Aulnay drowned in 1650, La Tour returned as governor; in 1653, to mend any conflicts, he married d’Aulnay’s widow.

The next year, Acadia fell to the British. Sir Thomas Temple came from England to be governor; his two deputies were William Crowne, of Massachusetts, and Charles La Tour. It turned out that both La Tour and his father had been Baronets of Nova Scotia, and La Tour received a large grant of land on this basis. Temple built a fur-trading fort at Jemseg in 1659, the first European fort on the St. John River itself. Although Charles II of Britain confirmed Temple’s grant in 1660 when the British monarchy was restored, the Treaty of Breda in 1667 returned Acadia once again to France. In 1663, King Louis XIV of France had abolished the commercial companies and instituted royal control over the colonies, and thus France’s North American colonies became the direct preserve of the state. The great age of imperial rivalry began.

Before this time, there is little mention of the Grand Communications Route. Native people continued to use the route as they always had, and the occasional French trader, traveller or missionary probably joined them. Once the king took control and the governor or lieutenant-governor of Acadia reported to the governor-general in New France, the situation changed. Now there was a command relationship between the colonies and a requirement to exchange official correspondence. The route began to take on administrative importance.

During this period, Louis de Buade, comte de Frontenac, the governor-general in New France, began granting large tracts of land as seigneuries. One of the grantees, Martin d’Aprendestiguy, Sieur de Martignon, received land on the west side of the mouth of the St. John River. There he rebuilt Fort Charnissay and renamed it Fort Martignon. Other seigneuries granted further up the St. John River began the European settlement of the route. However, the Acadians were not to live on their land grants in peace: this was the age of piracy, buccaneering and freebootery. In 1674, a Dutch captain, Jurriaen Aernoutsz, led an expedition from the West Indies against the British colonies. When he heard that the British and Dutch had signed a peace treaty, he turned against the French, capturing the French fort at Pentagoet (Castine, Maine). After he took Fort Jemseg on the St. John River, he allowed a French officer to go to Quebec to report the events. Count Frontenac then sent a force by canoe over the Grand Communications Route to ascertain the state of affairs and escort any French refugees to New France. This is the first known movement of European troops over the route. Having declared Acadia to be a Dutch colony and picking up a cargo of coal at Grand Lake, Aernoutsz departed. Dutch control was ineffectual, the New England colonists drove the Dutch out, and France regained control of the area.

This change of ownership had unfortunate consequences for the New England colonies. In 1687, Louis-Alexandre Desfriches, Sieur de Meneval, the newly appointed governor of Acadia, was ordered to keep foreigners — that is, British colonists — from fishing in Acadian waters and trading with the Natives, and was instructed to establish and enforce the western border of Acadia along the Kennebec River. Thus began the vicious raids known as la petite guerre that were intended to strengthen the French position and curb British expansion. The river system of New Brunswick was essential to organizing and mounting these raids. French-led war parties, which included Maliseet and Mi’kmaq warriors, gathered at Meductic and then followed the Eel River portage route to their forward base at Castine, Maine.

The best record of this period is the daily journal kept by Joseph Robineau de Villebon, commandant in Acadia. De Villebon arrived in Acadia in the summer of 1690, only to find that a Massachusetts expedition led by Sir William Phips had captured Port-Royal and taken away Meneval. De Villebon went to Fort Jemseg and explained the situation to the Natives and Acadian settlers there. He then went to Quebec, via the Grand Communications Route, and on to France. Phips had also captured the annual French supply ship at Port-Royal, and the presents and other goods destined for their Native allies had been lost. Now the Natives were in urgent need of powder and lead, so de Villebon arranged for a quantity of both to be sent back to them from Quebec. This is the first recorded instance of supplies being moved over the route from Quebec to Acadia.

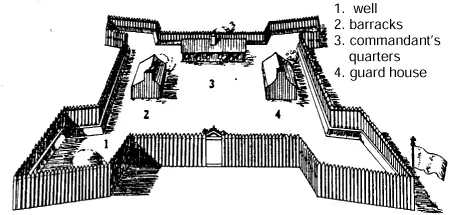

Fort Nashwaak (Fort St. Joseph), as envisioned in J.C Webster’s Acadia at the End of the Seventeenth Century. Constructed in 1692, the fort withstood a British attack in October, 1696, and served as the capital of Acadia until 1698.

On his return, de Villebon moved his headquarters from Fort Jemseg to a new fort at the junction of the Nashwaak and St. John rivers, the present site of Fredericton. Fort Nashwaak, or Fort St. Joseph, was two hundred feet square, with four bastions, and was surrounded by a palisade and ditch. It was conveniently located near the large Maliseet village at Aucpac, which had eclipsed Meductic in importance. De Villebon used this site as his headquarters to launch raids against the British settlements. In 1696, following the loss of Fort William Henry at Pemaquid, Maine, the New Englanders carried the war back to the French. A force under Major Benjamin Church ravaged Acadian settlements at Chignecto and raided the new fort the French were building at Saint John. A force under Colonel John Hawthorne then joined Church, and together they moved up the St. John River to attack Fort Nashwaak. In preparation for this assault, which began on October 18, de Villebon built a second palisade around the fort and mounted ten cannon and eight swivel guns on its walls.

The British set up camp and a battery across the Nashwaak River from the fort on the east bank of the St. John River, about where the Fort Nashwaak Motel now stands. After two days of ineffectual bombardment and harassment by the French and Native skirmishers in the woods, the British departed on October 20. They burned Acadian homesteads along the way, except for that of Sieur Louis d’Amour Chauffour at Jemseg, which was spared because of a note written by John Gyles. A New England boy who had been captured by the Maliseet in 1689, Gyles was befriended by the de Chauffour family, who managed to arrange for his release two years later.

This conflict reinforced the idea that, in order to defend the settlements along the river, its mouth at Saint John had to be secured. This logic, plus the need to protect the French privateers in the area, lead to the rebuilding of the fort at Saint John. In 1698, de Villebon completed the new Fort St. Jean and made it his seat of government; he died there in 1700.

De Villebon was the first European to make strategic use of the Grand Communications Route in time of war, and he understood its importance in the struggle for North America. His journal is full of references to couriers using the route to carry messages to and from Count Frontenac at Quebec. The preferred — and indeed the only practical — resupply route was by sea, but shipping was frequently interrupted by the British. Although more than one plea was made to Frontenac to replace lost supplies, with the exception of the powder and lead sent back to Quebec in 1690, there is no mention of any supplies being carried over this route. Troop reinforcements, however, came down from Quebec and prisoners were taken back to Quebec along the route. Canoes were dispatched to Quebec at least once and sometimes twice a month, and a round trip could take as little as twenty-one days. Thus, by 1700, the Grand Communications Route had become an important strategic factor in the administration and military affairs of Acadia.

Another issue that would affect the route arose in 1700. The British disputed the French claim that the Kennebec River, in central Maine, formed the western boundary of Acadia, the boundary that Meneval had been charged with enforcing. In 1700, a boundary commission consisting of Sebastien de Villieu and Captain Frederick Southack of Boston agreed on a compromise boundary at the Pentagoet River, but this agreement was never ratified. The international boundary between New England and Acadia, and later Maine and New Brunswick, would be a vexation for the next hundred and forty-three years.

The Treaty of Ryswick ended the French and British war in 1697. De Villebon’s successor, Jacques-François de Monbeton de Brouillan, moved the seat of government to Port-Royal in 1701 and razed Fort St. Jean. This decision left the Acadian settlements at Freneuse (now Sheffield) and Jemseg undefended, and when spring floods forced the settlers to abandon their land, they had to shift to other locations, such as Port-Royal. However, the French missionaries remained amongst their Native charges and continued to incite them in their continuing raids against the British settlements. Following the outbreak of war in 1702, the New Englanders sent unsuccessful expeditions against Port-Royal in 1704 and 1707. Then, in October, 1710, a combined British regular and colonial expedition finally captured Port-Royal. The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 confirmed that it would not be returned to France. The British renamed it Annapolis Royal and called their new colony Nova Scotia.

By treaty, the French ceded “all Nova Scotia, or Acadia, comprehended within its ancient boundaries” to Britain in 1713. The British assumed this declaration included New Brunswick and Maine as far as the Kennebec River. The French disagreed and claimed they had ceded only peninsular Nova Scotia. They began enclosing the British in this area by building up their strength on the Chignecto Isthmus, Isle St. Jean (Prince Edward Isl...