![]()

Chapter One

New Brunswick’s

Undeclared War, 1812

In June 1812, the United States of America declared war on Great Britain. But New Brunswickers and their neighbours to the south were not suddenly formal enemies. In fact, the last thing the British Empire — by 1812 at war with France off and on for nearly twenty years — needed was another war. With the exception of Spain, where Britain’s small army was waging a successful resistance lead by the Duke of Wellington, and Russia, all of Europe was under Napoleon’s yoke. Only the world beyond Europe lay outside Napoleon’s grasp, and access to that world and its trade was effectively controlled by the Royal Navy. Indeed, it was the sheer weight of British seapower, and its control over the free movement of people and trade, that ultimately drove America to its declaration of war. And it was the British desire to avoid that conflict by not immediately declaring war in response that left New Brunswick uniquely vulnerable in the summer and fall of 1812. The results were the waging of a four-month undeclared war by Lieutenant-Governor Smyth and the first and only privateering campaign launched by New Brunswick in the great age of sail.

War with the United States offered New Brunswick merchants, ship-owners and seamen three options: licensed trading, licensed warfare or smuggling. While hundreds of licences were issued to ensure a steady supply of flour and other foodstuffs to British soldiers, sailors and colonial subjects — including New Brunswick — at least ten New Brunswick-owned vessels also received one or more letters of marque entitling them to seize American shipping. The fact that many of these vessels do not appear to have made any prizes suggests that either privateering was not their primary focus or some may have used their letters of marque to disguise more covert activities. The majority of individuals and companies who participated in this activity were based in Saint John, but merchants and entrepreneurs from St. Andrews and Fredericton were also represented among the more than twenty individuals and businesses who invested in privateering between 1812 and 1814.

It is ironic that although New Brunswick was part of the most powerful maritime empire the world has ever seen, there was virtually nothing available in the summer of 1812 to protect its coasts from American depredations. Nearly two decades of war with France had reduced Britain’s thousand-ship navy that had triumphed at Trafalgar to a thin wooden line. The Royal Navy was so stretched just trying to protect its merchant trade from attacks by French and Spanish enemies in Europe and the West Indies, it could only spare twenty-seven vessels for the whole North American station that stretched from Newfoundland to the Caribbean. Many of these vessels were small, old or unseaworthy, and almost all of them spent from November to July protecting British shipping in and out of Bermuda.

The United States Navy was not much better prepared for war in early 1812. With no ships-of-the-line, seven frigates (a few dating back to the Revolution), and some smaller vessels, no dockyards and no real plan of action, the US Navy was undermanned, under-gunned and overwhelmed. Former President Thomas Jefferson had allowed the small American navy built up during the Revolution and the quasi-war with France in the 1790s to rot at the dock. The only solution for the United States was privateering. Two Baltimore schooners, the Nonsuch and the Rossie, shared the honour of privateering commission number one. Within days, dozens of captains and ship owners from Baltimore, New York and Salem were besieging their state governors for letters of marque.

Exposed and vulnerable to attack in its home waters, Atlantic Canada’s self-reliant maritime community took similar steps to protect itself even before Britain’s declaration of war in October. By 1812, most New Brunswick sailors, fishermen, merchants and ship owners knew the rules and regulations governing privateering. A formal declaration of war was usually followed by a prize act that allowed the government to issue letters of marque, or commissions, that entitled the holder to seize enemy vessels as prizes. To confirm that the vessel and cargo really were enemy property, that the capture had been legal, and that the crew and cargo properly treated, the captor was obliged to send the prize into port, where it was adjudicated by an Admiralty Court judge. In British North America, Lieutenant-Governors John Coape Sherbrooke of Nova Scotia and George Stracey Smyth of New Brunswick were responsible for issuing letters of marque, and the Vice-Admiralty Court in Halifax monitored legal matters.

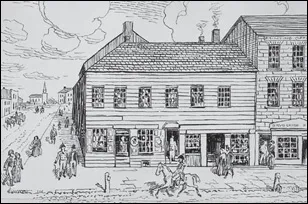

MacPherson’s Tavern (also known as the Exchange Coffee House), Scotch Row, Saint John, ca. 1812. Much of the business of privateering was arranged in such places, sometimes even the Vice-Admiralty Prize Court, and MacPherson’s Tavern was probably no exception. (NAC C-073563)

Once a prize was “condemned” or awarded to the captor and the vessel and/or cargo auctioned off, investors, officers and crews received their agreed-upon shares reasonably quickly. Despite court costs, salvage fees, the repayment of the costs of arming and equipping the privateer itself and other charges related to securing a prize, and provided risks to life and property were kept to a minimum, profits could be substantial. The New Brunswick privateer Dart is said to have earned each of her crew roughly $500 from their first cruise, a considerable amount given the average seaman of the period earned $15 to $30 per month. Although some considered privateering no more than legalized piracy, North America’s maritime communities welcomed privateering as a respectable, legitimate, effective and often profitable way of waging war.

The US declaration of war was signed on June 18, 1812, but communication was so poor at the time that news of the war did not reach Halifax for over a week. The news finally arrived on June 27, when the frigate HMS Belvidera (36 guns) limped into port with several dead and wounded sailors aboard. Three days earlier off Nantucket, Captain Byron, RN, had learned about the war the hard way — fighting off a determined attack by two 44-gun US Navy frigates, USS President and Constitution, and three smaller vessels under Commodore Rodgers. Surprised and seriously outgunned, Byron narrowly managed to escape the engagement but did seize three American vessels on his way home just to get even. The same day, a despatch boat from St. Andrews carried the news to the inhabitants of Saint John. Ready or not, on July 30 Captain Broke of HMS Shannon — later famous for its successful action against the USS Chesapeake off Boston — smugly declared that the British North American squadron “is in excellent service order and confident of destroying our Enemy’s little Navy if we are fortunate enough to meet them.”

Not everyone in the US, as we shall see, was pleased about the prospect of war with Britain, but President Madison, the Republicans and many along the mid-Atlantic seaboard were ready to fight. Emotions ran high. On June 20, 1812, Baltimore’s Federal Republican newspaper dared to criticize the government for rushing into war unprepared, and the next day a mob set its offices on fire. Soon the American coast was bristling with privateers ranging from heavily armed ships of several hundred tons carrying more than 150 men to open whaleboats manned by a few men armed with muskets. Some were so small that, in one case, the privateer was carried home on the deck of her prize! Ironically known as “shaving mills,” these small open boats, mostly from the coast of Maine, were rowed by up to thirty or so scruffy-looking men with little regard for either shaving or the finer rules of private armed warfare, especially those that prohibited attacks on land. Vessels such as the Weazel of Castine, terrorized inhabitants along the Fundy coast with frequent raids on shore and thefts of food, fishing gear and even women’s clothing.

The Capture of the British Merchantman Quebec by the American Privateer Saratoga, artist unknown. Saratoga was typical of the small, fast Baltimore Clipper-type ships that dominated privateering in the War of 1812. Quebec yielded a staggering $300,000 in prize money. (NAC C-040581)

The Royal Navy’s early attempts to sweep these small privateers from the Bay of Fundy drew blood on both sides. In early August 1812, in a harbour near Quoddy, Maine, HMS Maidstone and Spartan, 36 and 38 guns respectively, tried to seize the Portland privateers Mars and Morningstar mounting a couple of small guns each. Having been warned of the attack, the privateers fought back fiercely, killing or wounding twenty men before being forced to lower their flag. Respectful of the tenacity of their opponents, the British later sent ten boats and two hundred men to remove the captured crews and burn the vessels. A few days later, HMs hips Indian, Plumper, Spartan and Maidstone cautiously sent five barges and 250 men to attack the US Revenue Cutter Commodore Barry and the privateers Madison, Olive and Spruce carrying probably less than fifty crew altogether. During the first few months of undeclared war, Royal Navy vessels succeeded in capturing the US naval brig Nautilus, thirteen privateers, a revenue cutter, fifteen ships, four brigs, ten schooners and a sloop. On the other hand, with the exception of a few prizes taken by the USS Essex, most of the early American prizes were sent in by privateers.

President Madison’s declaration of war also caused great anxiety among the inhabitants of the District of Maine, who shared a long history and longer border with New Brunswick. In Saint John, readers of the Royal Gazette and Saint John Advertiser opened their papers on June 27 to read the following:

WAR! WAR! WAR!... The Inhabitants of East Port held a meeting this morning, when it was unanimously agreed to preserve a good understanding with the Inhabitants of New-Brunswick, and to discountenance all depredations on the property of each other. We also learn, that the Embodied Militia were ordered out.

During the long years of war against Napoleon, New England shipping interests had lost hundreds of ships, cargoes and crews to France and her Spanish, Neapolitan and Dutch allies. Along with the direct loss of property it caused, war at sea dramatically reduced trading opportunities and increased risk of capture by naval vessels and privateers. This raised insurance rates and drove up wages and shipping costs. The merchants knew all too well that the cost of this new war would likely come out of their pockets. Moreover, the economies of Maine and New Brunswick were closely linked, while the British depended heavily on American trade — especially agricultural products and the white pine cut in the forests of northern Maine and in the disputed territory of the upper St. John River.

The Licensed Trade

To secure the good will of Americans, Admiral Herbert Sawyer, commander of naval forces in North America, ordered his naval captains to treat any prisoners of war from the New England states with “great indulgence” and urged his men to avoid capturing small vessels of no value. By offering economic incentives to the merchants in nearby Maine, he hoped they would be less likely to turn to privateering and help to secure their continued trade with the British Empire. First, Sawyer convinced the Nova Scotia Executive Council to admit American goods traded duty-free at Eastport on Moose Island, Maine. Then British military, naval and civilian authorities began to issue licences to American ships willing to carry flour and provisions to feed British troops fighting Napoleon in Spain and Portugal.

Since New Brunswick could barely grow enough to feed its own population of seven thousand let alone extra British forces, it was critical that the existing trade between Maine and New Brunswick continue. Not only did St. Andrews’ citizens depend almost entirely on their American neighbours for flour, but the market at Saint John relied heavily on American oats and hay. In return for foodstuffs and a variety of contraband articles, New Brunswickers happily traded lumber, fish and cash. Neither side allowed a little thing like a declaration of war to interfere with their longstanding, usually legal, commercial activities.

During the first two and a half months of undeclared war, some five hundred licenses issued to Americans insured a steady supply of flour and provisions to British North America and the West Indies, to British troops in Europe and to British fleets in American waters. As early as July 15, the Commissariat in Saint John was advertising for fresh beef for His Majesty’s ships, and many of those who responded were Americans. At a time when money was scarce and British forces were offering hard cash, practical Yankee farmers felt that if the Royal Navy was buying beef it might as well be American. And how could a farmer be blamed if his cattle just happened to graze near the border where New Brunswickers could entice the animals across with baskets of corn? While some Americans balked at supplying enemy troops in North America, both the US Treasury Department and the US Attorney General’s office ruled that licensed trade with British troops in Spain was not illegal. Whether it was moral or not was up to the individual conscience of the supplier.

Despite British attempts to keep Americans from slipping into privateering, the war descended on the New Brunswick coast almost immediately. On June 30, 1812, an extraordinary issue of the Royal Gazette and Saint John Advertiser reprinted the American declaration of war. Two days later, Nova Scotia’s Lieutenant-Governor Sherbrooke issued a proclamation urging residents of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to “abstain from molesting the inhabitants living on the shores of the United States ” as long as the Americans left them alone. The Baltimore Niles Weekly Register denounced Sherbrooke’s proclamation as an attempt to encourage treason, but he had little choice. Scrambling to end the conflict by diplomacy rather than combat, the British government refused to issue a declaration of war right away. It was not until October 13, 1812, nearly four months after the American declaration, that Britain officially declared war.

In the meantime, Sherbrooke and Smyth in New Brunswick were caught in a legal no man’s land. Without a declaration of war there could be no letters of marque and no privateers, yet something clearly had to be done to respond to the undeclared war in the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine. Moreover, provincial merchants and ship owners, afraid that the navy would capture all the prizes before they could get to sea, clamoured for commissions to protect themselves and their property. Sherbrooke’s solution to the tricky problem of undeclared war was to issue carefully worded letters of marque under his own authority. His first letter, issued against France and the Batavian Republic [the Netherlands ], provided the large 623-ton armed trader Caledonia with the option of prize making on a transatlantic voyage in July 1812. In August, Sherbrooke issued a second letter of marque against France and unspecified “other enemies of the King of England” to the famous schooner Liverpool Packet, Atlantic Canada’s most successful privateer. A former slave ship turned packet vessel then privateer, the Liverpool Packet brought at least fifty prizes into court and destroyed or released many more. Her numerous cruises under several captains, among them Caleb Seeley of New Brunswick, earned her a reputation as the evil genius of the American coasting trade and enriched her owners with thousands of dollars in prize money. Since New Brunswick’s maritime settlements were under a similar threat, Lieutenant-Governor Smyth had no choice but to follow suit: in the summer and late fall of 1812 New Brunswick fought back.

Provincial Privateer Chasers

In early July, the Nova Scotia Gazette noted that the 21-ton privateer sloop Jefferson of Salem, Massachusetts, had gone ashore at Moose Island, home to both British and American citizens. Despite a warning from the local American Committee of Safety not to harm any of the inhabitants, the privateer sailed into Snug Cove and boldly cut the mooring cable of a British schooner. Fortunately for her owners, the vessel drifted ashore and escaped capture. This scare might have prompted a later report that some inhabitants of Moose Island who were removing their families and estates to the mainland had been insulted and threatened b...