![]()

1 The Cracked Dish

Soft rain. Water tanks on roof cleaned.

Entry in the Agapemone diary on

Tuesday, 24 February 1948

Twelve pairs of eyes!

Eleven old ladies and my sister. And they were all staring at me. I didn’t know how Margaret had made it to the dining room so fast. We had been playing on the swing on the upper lawn when the quarter-to-one bell had rung. Even though she was five years older than me, and a much faster runner, she mustn’t have washed her hands or brushed her hair to have got there so quickly. I knew Ann wouldn’t be there. At nearly 14 she was deemed ‘sensible’ enough to lunch with our mother and grandmother.

‘You’re late, Catherine.’ Eighty-six-year-old Emily Hine glared from her seat near the head of the long dining table. The elastic edge of the hair net she wore over her yellowy-white hair gave her an extra frown. Her jet necklaces jangled on her ample chest as she took a noisy disapproving breath and boomed, ‘Again!’

I hated her calling me Catherine, even though it was my real name – Catherine Jane Read, to be exact; I preferred Kitty. But I was far too scared to argue with this impressive old lady, who favoured fox furs with grinning heads and boot-button eyes on the rare occasions she ventured beyond the community walls.

‘Sorry, Emily.’ I stared at my scuffed shoes and fallen knee socks. I stole a glance at Margaret, sitting smugly in her seat near our nanny, Waa. My sister’s big brown eyes – far larger than Ann’s or mine – were alight with mischief. If she pulled one of her faces, I would giggle.

A watery sun shone through the tall windows, filling with a soft light what was the biggest dining room in the world. The light bounced off the huge gilt-framed mirrors hanging above the marble fireplaces at each end of the room and made the heavy silver cutlery and huge cruets on the long table glow rather than sparkle. The table seated 30 and still left room for an upright piano and a ‘withdrawing area’ of sofas and wing chairs.

I hurried to my seat between Waa and another of my favourite old ladies, 92-year-old Alice Bacon, who made sailboats out of squares of coloured paper, which I was allowed to launch in the birdbath in my grandmother’s private garden.

Everyone was watching me. And not just those seated at the table. ‘Dear Belovèd’, as everyone called our grandfather, followed my every move with his sad, soulful eyes. Wearing a dark suit with a stiff collar and with his grey hair parted in the middle, he stared down at his dwindling flock from his portrait above the ornate mahogany sideboard. He had ‘passed over’, as everyone there called dying, when my mother was just 17, but his picture was everywhere: above the huge dining-room sideboard, high on the parlour wall, above the stairs leading to ‘Granny’s End’. Everyone kept telling my sisters and me how wonderful he was. I thought he looked sad and . . . was it lonely? But that didn’t make sense, I told myself, as I slid into my seat. He had been surrounded by lots of people, all of whom loved him very much, so he could never have been lonely. I would be grown-up before I would begin to understand the sentiment that lay behind my grandfather’s enigmatic expression in the portrait.

‘She wasn’t very late this time,’ bellowed enormous Olive Morris. Her ear trumpet, which she had painted to look like an African snake, swung as she turned to get her sister’s attention.

‘You’re shouting,’ mouthed her sister. As petite as Olive was large, Violet had been one of England’s first women architects, something her sister informed me of regularly with pride.

‘She’s always shouting,’ I heard someone mutter.

I stared at one of the mantelpieces and its display of bronze hunting dogs with dead rabbits dangling from their jaws. Normally I never looked at them, especially if rabbit was on the menu. But I had grown bored of counting chairs – 12 being sat on and 18 not being sat on.

I bowed my head and shut my eyes in preparation for grace. I didn’t want to attract any more attention. One day when I hadn’t shut my eyes, Emily had noticed and told me off. She must have been peeping too, to catch me.

‘For what we are about to receive may we be truly thankful,’ intoned Violet.

As if on cue, the dining-room door opened and in came Ethel, the housekeeper, followed in procession by Lettit and Cissy, two tiny Welsh sisters. The three elderly women, worn pinafores covering their old-fashioned dresses, each carried a large porcelain dish. These dishes were covered by Victorian silver domes to prevent the food getting too cold on its long journey from the kitchens. I guessed it would be cold mutton for lunch. It had been hot mutton yesterday. I didn’t like either. I had thought about smuggling our Great Dane, Gay, into the dining room and slipping her my meat, but she was too big to go under the table. So now I was faced with a mealtime pushing slices of gristly mutton around my plate and trying to make them disappear.

Ethel knew I disliked meat, so she served me the smallest slice she could find on the huge porcelain platter, and Lettit and Cissy both let me take more than my fair share of boiled cabbage and potatoes. I spooned on a lake of mint sauce to disguise the meat, but it merely turned the fat a bilious green.

Absorbed in the movements of these pale green globs, I jumped at Emily’s booming voice once again. ‘The dish is cracked!’ she shouted, and snatched the serving spoon out of Cissy’s hand. She whacked the cabbage dish. There was a telltale clank of cracked china. ‘I knew it,’ she cried and hurled the spoon across the table, straight at me.

I ducked. The spoon sailed past me and bounced on the carpet behind my chair. I had barely turned around again when Emily’s blueveined old hands reached for the dish and wrenched it away from Cissy.

This time it was the dish that came flying through the air. It exploded against the wall, leaving a cascade of broken china and limp cabbage. Rivulets of pale, watery green poured down the wall and formed a pool on the Indian rug.

‘Belovèd would never have allowed a cracked dish,’ she bellowed. Everyone stared in stunned silence. Some of the old ladies were openmouthed. I could see their half-chewed food.

‘What happened?’ enquired 86-year-old Toto, one of my favourite old ladies, but near-sighted to the point of blindness. She turned her head from side to side in an effort to focus on the disturbance, looking just like Gay when she sniffed the wind.

No one answered. Then suddenly Emily was surrounded by old ladies. ‘There, there,’ comforted one. ‘I know, I know,’ muttered another. ‘Going senile, I shouldn’t wonder,’ pronounced Olive, as Emily was led muttering from the dining room and the mess hastily wiped up.

Margaret and I giggled over the incident that afternoon with Ann, but I had to wait until bedtime when Waa was tucking me in for an explanation. ‘Why did Emily throw the dish, Waa?’ I asked.

‘She was cross about the dish being cracked. She’s an old lady, Kitty.’

‘Did she get into trouble?’

‘No, Kitty, she didn’t. Everyone understands.’

‘I don’t.’

Waa stopped tucking me in and sat on the edge of the bed. ‘You would have to have known your grandfather, Kitty, to really understand,’ she said, stroking my hair. ‘Everything seemed possible when Dear Belovèd was alive. He was such a wonderful man, you just wanted to always do your very best, every hour of every day. I think what upset Emily today was a cracked dish being used. It would never have happened in Belovèd’s day, not because he would have been cross but because even the slightest imperfection was unthinkable . . .’

‘But—’ I began.

‘Shhh,’ she soothed. ‘You’ll understand. One day.’

* * *

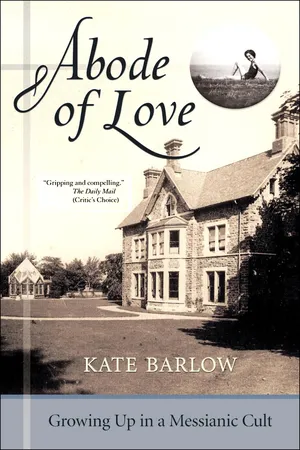

It was to be many years before I understood what Waa meant, but within a few weeks of arriving to live in the ‘Agapemone’ – a Greek word, my sisters informed me, that means ‘abode of love’ – I had divined the way my strange new home worked, in the way that young children often instinctively can. I had liked it immediately: its vast, mostly unkempt gardens, more than 20 bedrooms, central heating and its chapel, known simply as Eden. Plenty of room for my mother, my two older sisters and me, plus our 79-year-old nanny. Soon I learned not to fear the very old ladies who inched their way around dressed in fashions the like of which I had only seen in history books.

This shabby yet luxurious mansion in Spaxton, Somerset, was, I soon decided, much nicer than the draughty, spider-infested houses we had rented in nearby villages since my parents’ marriage had collapsed following my father’s return from Germany, where he had been detained in a prisoner-of-war camp. I had only ever seen my father once and my parents had never owned their own house. Perhaps he never understood that my mother had believed that when they married she had put her strange background behind her. To return home, her marriage in tatters, meant she had failed both in her marriage and in her escape.

And, already a veteran of my small, loving boarding school (I had been sent there aged five, the previous year), I found comfort in the institutional order of my new home: the bells which summoned the faithful to meals; the obligatory post-luncheon ‘quiet time’, which resulted in hours of unsupervised freedom for us children; the elderly members of the ‘Kitchen Parlour’ ready to cater to my every want.

I stopped being afraid of my fierce grandmother, who ruled from her wing in the east end of the mansion. Autocratic and above the daily comings and goings of the community, she rarely even ventured beyond the baize door which marked the wing of the mansion still referred to as ‘Belovèd’s End’.

I soon learned – even if I failed to understand – that next to her in precedence within the community came my mother, Lavita, then thirty-eight, and her two older brothers, David and Patrick. Patrick didn’t live with us but visited daily from his own home some miles away. David, the eldest and an officer in the Merchant Navy, was often away at sea.

I grew to love David. I sometimes even secretly wished he was my father. When he arrived home on shore leave, sometimes in his uniform and driving a Rolls-Royce, or some other luxurious car he always rented, I could have burst with pride. I never tired of listening to my mother tell of how brave he had been during the war when he was on the North Atlantic running the gauntlet of U-boats in an unarmed merchant ship. My mother later told me that, ironically, his most serious injuries were sustained when he was attacked by two South African soldiers in London while on leave. She explained that Merchant Navy officers didn’t wear uniform while off duty, and the two assailants probably hadn’t realised he was serving his country.

I thought the silk hanky he always tucked into his shirt cuff very dashing and loved the smell of his cologne. He had learnt to play the piano before the war and had also studied at the Sorbonne. He would tell me of his days in Paris in the 1930s, where he had mixed with Elizabeth David, the famous cookery-book author, and Josephine Baker, the black jazz singer. He was very proud to have been personal assistant to the 7th Earl Beauchamp, who had served as governor of New South Wales in Australia and warden of the Cinque Ports until his resignation in 1931 following his ‘outing’ as a homosexual. My uncle had been at the earl’s bedside when he had died in New York seven years later.

Uncle David’s most important quality, however, as far as I was concerned, was his kindness towards our mother, especially now that she was divorced. Even though somewhere he had an ex-wife and a daughter, his sister came first in his heart and he never failed to bring her a present each time he came home. He wrote to her frequently and, whenever possible, paid for her to visit him in one of the ports he stayed in on leave for weeks at a time.

But where my feelings for Uncle David were uncomplicated, it was a different matter with his younger brother – referred to as ‘Panion’ by the old ladies (when he was born, he was deemed to be a companion to his older brother). He could be charming, and often was when he wasn’t drinking. Then he was fun to be around, with his stories of the racecourse and market day; letting me handle the ferrets that he kept in cages at his home and his pet dogs, which he would exercise by making them run after his vehicle. But it took very little for his handsome features to suddenly become suffused with fury and his cursing to send me running. What was he so angry and frustrated about? As a child, I hadn’t a clue. I understand better now how his strange upbringing had left him a confused and frustrated man. Yet I loved the aura of energy that filled any room he was in and I tried to imitate his constant tuneless whistle, which would start my grandmother muttering, ‘Empty vessels make most sound.’

Uncle Pat was always immaculately turned out, mostly in breeches, with gaiters shiny enough that I could see my face in them, and trilby hats, which gave him a decidedly gentrified appearance. There also clung to him the faintest aroma of the stableyard, one even more pronounced on market days when his clothes were redolent with the smells of the town’s local livestock market and the numerous public houses he frequented. I never remember his holding down a job – except for a brief spell on a factory production line – but he seemed to live in comfort with his wife ‘Babe’, a local farmer’s daughter, and their growing family in a house in a nearby village given to him by my grandmother. He was never short of cash, always appearing to have enough to deal in pigs and other livestock – and be well known in local betting and racing circles. He spent most afternoons barking instructions to his bookmaker over the phone in my grandmother’s downstairs drawing room, which used to be my grandfather’s study.

Uncle Pat also had the most beautiful copperplate handwriting, which I again unsuccessfully tried to copy, although even at six I could spell much better than him. Waa explained to me how he had wanted to be a farmer or an auctioneer, but that my grandmother had ‘put her foot down’. Grandmother couldn’t stop him dealing in livestock, but it just would not have done to have had a member of the ‘Holy Family’ working as a farm labourer. In the 1950s he was to spend many months in a sanatorium, recovering from tuberculosis.

Years later, during a particularly difficult time for my Aunt Babe, she told me how, as a young man, Pat had worked for her father, who had become concerned that his daughter might be falling for the handsome young man. ‘Don’t marry him,’ he had cautioned her. When she asked her father why not, he told her it wasn’t that he didn’t like the young man – he did – ‘But he won’t make you happy,’ he’d said.

On special occasions, or when she decreed, my grandmother would invite us children to take tea with her in her upstairs boudoir which overlooked the small, square garden bound by Eden, the estate wall and my favourite hiding place, the huge blue cedar bordering the long driveway to the front door. It was a shaded room, full of light and with that secure atmosphere which children love. It was filled with graceful Edwardian furniture, so was different from the rest of the mansion with its ornate Victorian contents. My favourite piece in the room was the tall corner cupboard filled with intriguing objects: pieces of delicate porcelain, and tiny wooden and ivory carved animals, all souvenirs of her and my grandfather’s travels in Europe and Scandinavia.

Granny’s Windsor armchair was always drawn close to the fireplace, which boasted a glowing wood flame on all but the very hottest days. An old-fashioned radio stood on a nearby table. Sometimes we would be allowed to sit with Granny after lunch and listen to programmes on the wireless while she dozed on the chaise longue. Other times, she would tell me stories about her childhood and the days before she met grandfather. I never once remember hearing her refer to him as Belovèd, and it would be years before I learned that the name – or, perhaps more accurately, his title – was taken from the Song of Solomon.

I was always expected to arrive exactly five minutes early for tea to help Granny hunt for her false teeth, which she regularly removed for her rest and just as regularly misplaced. Yet she made a regal figure in her blue chiffon veil and with her ramrod straight back. Years later I would learn that outsiders assumed her veil to be some kind of bizarre badge of office. My mother maintained it was nothing of the sort, just that my grandmother had suffered a severe ear infection as a young woman and wore the veil to protect her ‘delicate ears’.

By the time my sisters and I came to live at the Agapemone, she was also blind and suffering from cancer of the nose, which left a raw wound that had to be dressed daily by a visiting nurse. But none of her very real afflictions daunted her, and she dominated the household and her children until the day she died.

In the early days, I didn’t give much thought to the old ladies, except that there seemed to be a lot of them and that they obviously were of lower status than my grandmother, mother and uncles – and, to a lesser extent, us three. We were loved by the old ladies in a Victorian ‘children must be seen and not heard’ fashion and supervised by our nanny. I certainly had no idea they were the survivors of a band of followers who had been led by my grandfather and his predecessor, and who, having donated their personal fortunes on joining the community, had been rewarded for their generosity with a life of ease.

At the time, I didn’t realise just what highly gifted women they were. They had no doubt been ostracised as ‘eccentric’ by mainstream Victorian and Edwardian society, but here, in this weirdly emancipated community, they flourished. Violet Morris was still busy designing houses: the latest, at the far end of the village, was one of many examples of her talent in and around Spaxton. Her sister Olive, a self-taught engineer and woodcarver, had learned to drive in the early 1900s and still spent her days in her workshop, knee deep in shavings. Examples of her carvings appeared everywhere and were proudly pointed out to me; one day I would learn they filled not only the community but the London Ark of the Covenant as well. The two sisters lived in one of the three ‘gates’, large comfortable houses built at the northern, western and eastern points of the estate.

Some of the other ladies were renegades from the wealthy Victorian merchant class, like Ada Kemp, of the Kemp biscuit family. Toto, whose real name was Phoebe Ker, was the daughter of a wealthy merchant who had paid the printing costs for Voice of the Bride, the community hymnal once used in the chapel and the London church. Her brother was a publisher in America and her niece, Grace, made regular, lengthy visits to Spaxton following her retirement as headmistress of a girls’ school on Long Island, New York. Time and again it would be myopic Toto who would sense emotional distress and come to the rescue of those caught up in the legacy of our grandfather’s outrageous claim.

Waa had told us that she herself was a Wiltshire country girl who, until leaving to help our mother with us, had spent her entire adult life in the community after her brothers had been killed in various Empire wars. She told us how ‘Dear Belovèd’, our grandfather, had appointed her nanny to my uncles and mother when they were born and, in turn, ...