![]()

Part One

A NEW PARTY

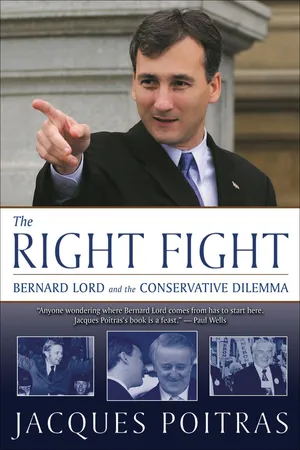

Richard Hatfield receives a Valentine — a petition signed by francophone

Conservatives supporting his leadership — from MLA Percy Mockler in

February 1985. COURTESY OF PERCY MOCKLER

![]()

Chapter One

JIM PICKETT LIGHTS A MATCH

AS THE TRAVELER GLIDES OFF the Trans-Canada Highway and downhill to Perth-Andover, the noise and speed of the outside world give way to the soothing scene of the St. John River flowing serenely south. The little village that occupies the flat land on both banks is as quiet and calm as the current itself. At the bridge, drivers ease to a halt to yield the right-of-way to a neighbour or friend waiting to turn onto the narrow iron span.

Occasionally, when thick ice jams the river, or heavy snowfalls lead to large spring freshets, the water swells over its banks and spills into Perth-Andover’s streets. Then the residents, as is their custom, press themselves into service to help each other out.

Tumult and upheaval are otherwise rare here. But late in the day of May 6, 1985, something was stirring.

Spring had come to Victoria County, but the air was cool, and there were occasional rain showers as Jim Pickett drove through the centre of town and out onto the highway. He accelerated north, ascending across the slender tail of the great spine of the Appalachian mountains, extending across the border from Maine. It would take Pickett less than half an hour to reach the New Denmark Recreation Centre, where the Victoria-Tobique Progressive Conservative riding association was holding its annual meeting in classic St. John River Valley style: a potluck supper, followed by some political speeches, then the business meeting itself.

As Pickett ascended the Four Falls hill and the great stone shape of St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church came into view, the man in the passenger seat spoke up. “Jim Pickett,” he said, “I understand you are up to something.”

Pickett glanced over at his passenger and wasn’t sure how much to say. It was true, he was up to something. But it might be awkward explaining his plans for the evening to the man in the passenger seat. Stewart Brooks, after all, had represented the riding of Victoria-Tobique as a Progressive Conservative member of the Legislative Assembly for more than two decades — from 1952, when he was part of Hugh John Flemming’s surprise victory, through the Liberal 1960s, to 1976, when he retired from politics and was replaced in a by-election.

Pickett hadn’t been much of a political person before Brooks came to his door to ask him to manage his final campaign in 1974. Pickett’s father and uncle had attended the occasional meeting, and in the 1920s his grandfather had been an MLA for the United Farmers, a protest party that briefly appeared on and then vanished from the New Brunswick political scene. Maybe that was where Pickett got his rebellious streak: most valley people were deferential to their politicians to the point of being almost free of cynicism. “When I was growing up,” Pickett explains, “when Hugh John Flemming’s name came up at the dinner table, or Stewart Brooks or [federal MP] Fred McCain, there was no laughing or making fun or calling people jokers. This was politics. These people were respectable people.”

Now Pickett had lost respect for the politician who mattered the most — to himself, to Brooks, who shared his feelings, and to the man in the back seat, a local road contractor named Bob Birmingham, who was known to land the occasional government highway job.

“All I’ll tell you, Pickett,” Brooks said, “is if Richard Hatfield gets a chance to respond, he will destroy you.”

It was the last thing Pickett wanted to hear. He’d been agonizing for weeks over what he was going to do tonight. “Everybody wanted to do it,” he says today, “but no one would do it. Most of them had government jobs. It was a personal thing. No one knew I was going to do it. I was planning it for about two weeks.”

He had sat at his kitchen table, going over his list of insurance clients. “I tried to fathom if there was any way Richard Hatfield could destroy my insurance practice if I did this,” he says. “I said, ‘What is going to happen to my Tory clients?’” And so Jim Pickett pondered. The political climate in the PC party was hot and dry, and he proposed to light a match.

But what choice did he have? His premier — his leader — was spiralling out of control. Richard Hatfield had been charged with possession of marijuana the previous autumn, accused of carrying some weed in his bag during the visit of Queen Elizabeth to New Brunswick. No sooner had the premier recovered from that than two St. Thomas University students had accused him of using the government plane to ferry them to Montreal and supplying them with cocaine at his Fredericton home. The last straw had been an interview with Hatfield on CBC Radio following the premier’s courtesy call to a US-based anti-drug caravan that had stopped in Fredericton. As Pickett recalls it today, when the reporter asked Hatfield why he had decided to visit the activists, he replied that he didn’t know — that he had been told by advisors to be there.

Once Pickett had admired Richard Hatfield. “He seemed pretty astute. He knew how to get people to work. He had representation on every country road in the province. He was determined to get support from every person in the province, and he did a pretty good job of it.” Lately, though, doubt had been setting in. It had started with Hatfield’s initiative to expand the language rights of New Brunswick’s French-speaking Acadians, who made up about a third of the province’s population. The premier had given legal force to sections of the Official Languages Act that had not been implemented since the legislation became law in 1969.

“A lot of people didn’t like it,” Pickett says now. “I’m from Andover, and Andover’s pretty English. In a year I wouldn’t hear a word of French at church or at the bank. I understood what Hatfield was trying to do. I wasn’t all that impressed with it, but that was the way the world was turning.” Yet the premier seemed to be losing touch with the opinions of people like Pickett or another Tory member from the riding, Kevin Jensen. “French and English have lived in harmony and wouldn’t do too badly if politicians would leave them alone,” Jensen would say.

But Richard Hatfield wouldn’t leave the language issue alone. He had recently commissioned a study, Towards Equality of Official Languages in New Brunswick — better known as the Poirier-Bastarache report — that was now the subject of public hearings around the province. The report’s recommendation of a dramatic expansion of the francophone presence within the civil service was threatening the old Tory view of English New Brunswick. And there was the absurd and expensive notion of requiring every last city, town and village — even overwhelmingly anglophone ones — to provide bilingual services. And so at the very moment the drug scandals exploded into the public consciousness, old-stock party members felt unsettled about their leader. Unsettled, yet unwilling or unable — precisely because of their conservative nature — to rock the boat.

Only if someone forced the issue might things change.

Pickett turned right at St. Patrick’s and followed the Limestone Siding road back down into the valley of the St. John River, crossing a one-lane bridge, then hurrying along a country road toward New Denmark. The meeting was on the ground floor of the recreation centre, in a hall wider than it was long. The room was full that night. Pickett remembers it as “a real feast. It’s a real opportunity when these farm families bring their potlucks.”

The riding of Victoria-Tobique is English-speaking, except for some francophones along its northern edges, on the boundary with Grand Falls. That bilingual town is where the English Protestants of the St. John River Valley give way to the French Catholics of Madawaska County. New Denmark itself had started as a settlement of Danish immigrants, encouraged to move into the area to act as a buffer between the two groups. So it was an appropriate setting for an event that would set in motion a struggle within the Progressive Conservative party that was, at its core, a showdown over language.

As the Tories tucked into their meals, Pickett was still wavering on whether he would go ahead with his plans. He had lined up Kevin Jensen, a local farmer, to play a role in the drama that was about to unfold. But Jensen hadn’t arrived yet. Pickett ducked out to find Jensen still at his farm down the road, finishing up some work in the field. He eventually arrived at the hall as the meal was wrapping up and the assembled Tories were preparing to move to the business meeting proper. But as Jensen entered the room, he was intercepted by three Tories, each with a vested interest in scuttling Pickett’s plan.

There was Bob Birmingham, the beneficiary of government highway contracts, who had travelled up from Perth-Andover with Pickett and had gleaned a little of what was coming. There was Bernard DeMerchant — “a big-time Tory,” as Jensen puts it — with strong connections to the party brass in Fredericton. And there was Mac Macleod, the universally respected MLA from Albert County and minister of agriculture in Hatfield’s cabinet. “They sort of moved me into the corner and said, ‘You can’t do this,’” Jensen recalls. “They said, ‘Nobody wants this to be done.’ They put the push on. They tried to make it look like I was the only guy in the world who wanted to do this and it would be a terrible thing.”

Jensen was unable to resist the strong-arm tactics of the three big Tories. “I told them I wasn’t going to do it.” Jim Pickett’s carefully scripted drama was in trouble.

The meeting got rolling with preliminary remarks and routine business. As it proceeded, there was a bustle of activity back at the door. Tories glanced over to see Jean-Maurice Simard sweep into the room. Simard was Hatfield’s French lieutenant, the premier’s most trusted ally in the effort to win Acadian votes and one of the most powerful ministers in the PC government. “When he walked in, and he walked up along the wall to the front where Hatfield was sitting,” Pickett says, still astonished eighteen years later, “there were 150 people sitting there, and they all started to boo. They roared.”

These were Tories, loyal Tories, long-time Tories, jeering a fellow Tory. An important Tory.

A few days earlier, these English-speaking Progressive Conservatives of Victoria-Tobique had driven a half-hour upriver to Saint-Léonard, a French-speaking town in Madawaska County, to attend a federal PC meeting. Saint-Léonard was in a different provincial riding, but it was part of the same large federal constituency of Madawaska-Victoria as Perth-Andover and New Denmark. Simard, as the most prominent provincial Conservative in the federal riding, had addressed the crowd of mostly bilingual francophones and unilingual anglophones.

“He spoke well over an hour, and he never uttered a single word in English,” Jim Pickett says. “We weren’t very impressed with that.”

Simard was hardly the kind of Tory the members in Victoria-Tobique were used to. Passionate, moody and stubborn, he had a shock of thick black hair and large, bushy eyebrows that gave him the appearance of an owl as he watched over the language issue from his perch in Fredericton. Simard was known to be from Quebec, and his temperament and his fiery speaking style were more suited to the personality-driven politics of his home province. His French-only speech in Saint-Léonard reinforced the mistrust many anglophone Tories felt toward him. “They didn’t like him,” Pickett says. “He seemed to be running the Hatfield government. It seemed like Hatfield was giving him free rein.” So when the provincial riding executive in Victoria-Tobique scheduled their annual meeting for English-speaking New Denmark, they opted not to invite him.

Now, in typically brazen fashion, Simard had shown up anyway. For Jim Pickett and his plan, which had come so close to being derailed by Macleod, DeMerchant and Birmingham, Simard’s appearance was fortuitous. Simard was a polarizing figure in the PC party, and he polarized everyone in the room to Jim Pickett’s side. “If Simard had not come there that night,” Pickett says, “this thing would not have happened.”

As Hatfield addressed the crowd, Pickett settled into a seat about two-thirds of the way toward the back of the room. He took an envelope from his pocket, placed it on his knee and began jotting down notes as the premier spoke. He saw Jensen, standing near the back of the hall. When the premier finished, Pickett leapt to his feet, abandoning his plan for Jensen to make the first move, unaware that his farmer friend had chickened out anyway.

“I was pretty involved with myself,” Pickett admits. “I felt pretty confident I could say something. I wasn’t going to let it not happen.” The chairman of the meeting acknowledged Pickett, and the premier turned his attention to the insurance agent.

Pickett glanced down at his notes and took a breath. What he was about to do had been done several times before in political parties, but only when they had been in opposition, when there was an argument to be made that the party leader could not win. No one had yet attempted it against a leader with a track record of success, in a party in the midst of governing. But Jim Pickett looked up at Richard Hatfield. Then in his fifteenth year in power, on track to become New Brunswick’s longest-serving premier, Hatfield had led the Tories to four consecutive majority governments and scored unprecedented victories for the party in French-speaking New Brunswick.

Jim Pickett told the chairman that he wished to move a resolution: that the Victoria-Tobique riding association request that the provincial PC party, at its next annual meeting, review the leadership of Richard Hatfield so as to remove him as leader and as premier of New Brunswick.

* * *

Revolution was in the air that spring in New Brunswick, even among those who seemed the very antithesis of revolutionaries.

Bev Harrison was the MLA for Saint John Fundy. A Newfoundlander and a monarchist, he felt a kinship with his Loyalist constituents; descendants of the colonists who had opposed the American Revolution out of devotion to the King, they had fled to the safety of British North America. Harrison also rejected the “rights revolution” of Pierre Elliot Trudeau — the 1982 patriation of the Constitution and the creation of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which protected linguistic minorities in Canada, including New Brunswick Acadians.

More recently, Harrison had been fighting revolution in the government civil service. The Poirier-Bastarache report, which had so angered the Tories in Victoria-Tobique, had alarmed Harrison as well. Its stated goal of increasing the number of Acadians holding government jobs seemed to break the unwritten understanding that had been reached with English New Brunswick: make your children bilingual through French immersion, and they will be able to get jobs in the public service. But hiring bilingual anglophones, capable of serving both language groups, didn’t satisfy Poirier-Bastarache.

“This report is saying you must hire Acadians. For me to be bilingual, my promotional possibilities would be stifled,” Harrison had told the Saint John Telegraph-Journal the previous December, when the report was just beginning to stir controversy. “Because there’s a period of time when you must have affirmative action for Acadians. You’ve got to get the percentage up. And to do that, you’ve got to slow down the anglophone promotions to zero.”

Yes, Harrison opposed revolutions. Yet he himself was now bringing one right into the Conservative caucus.

For Harrison was the chairman of caucus, the man whose job it was to strive for unity among MLAs. Instead, he was stoking conflict. Like other Tories, his concerns about Hatfield had begun with Poirier-Bastarache and were now inflamed by the premier’s personal scandals. Both ran counter to — and seemed to outright offend — the prim, proper conservative way of seeing the world that had prevailed in the PC party before Richard Hatfield came along.

The same night Pickett stood up and called for Hatfield’s ouster to the premier’s face, Bev Harrison rose to speak to the PC riding association in his constituency of Saint John Fundy.

He pointed to the party’s defeat in a by-election in Riverview the week before, a defeat many blamed on the premier’s drug scandals, but also one that had unfolded in a traditionally Conservative riding where hostility to Poirier-Bastarache was high. Harrison “was very forceful,” remembers Hank Myers, the MLA for the adjacent riding of Kings East. “He was very serious. He said the premier was bringing disgrace to the party — to the effect that if the premier cared about the party, he would resign.”

A stunned silence fell over the room. Bev Harrison, the very image of the loyal British gentleman, was starting a revolution against Richard Hatfield.

* * *

That same night, a hundred miles east, Irène Guerette, a francophone from Saint John, was taking a breather from the grim task of studying the divisions in New Brunswick society.

Guerette co-chaired the committee studying the object of Bev Harrison’s contempt, the Poirier-Bastarache report. After spending the fall at information sessions designed to spread the word about the report’s contents, the committee was now soliciting feedback from citizens on the merits of the recommendations.

Irène Guerette was losing her faith in the ability of French and English to live in harmony in New Brunswick.

The committee was on friendly ground on the night of May 6. At the hearing in Bouctouche, a mostly francophone town in coastal Kent County, people reacted well to the recommendations. But within days, the committee would move on to Moncton, historically a crucible of English-French tension. Guerette had been reading some of the briefs submitted in advance.

“Destroying a province to satisfy a few Acadian fanatics is next to a sin,” wrote Mrs. Fern Hutt of Moncton in a typical letter. “My French friends and neighbours were beautiful all those years ago. Today I feel differently towards them, and I blame these changed feelings on this very stupid, unnecessary and unwarranted Poirier-Bastarache report.”

Mrs. Hutt was not unusual in claiming anglophones and francophones got along much better back in the days when there were no French-language schools, courts or government offices — or rights. Such letter-writers claimed to be open and welcoming to Acadians, except when their demands became unreasonable. But the prevailing definition of “reasonable” seemed to harken back to the nineteenth century. Many letters urged not only trashing the Poirier-Bastarache report but also repealing the 1969 Official Languages Act that had first guaranteed rights to the Acadian minority.

And there were more sinister missives.

“Mr. Porior [sic], you asked to hear from the silent majority, well here is one and no doubt you will hear from the majority,” said one anonymous letter. “You and Bastarache have really started something that is going to take years to die down. People are going to get violent. You, Bastarache, Simard and Hatfield should head for Quebec where you will be safe. Most English speaking people would like to speak several languages but they don’t like French rammed down their throats, which only brings on hatred, call it off before it is to late. There could be bloodshed.”

More revealing of the depth of the problem facing Richard Hatfield and his beloved Progressive Conservative party were comments like those of T. Majensky. “I’ve voted Conservative for the last time,” he wrote on a comment card he had filled out at an information session the previous autumn. Majensky lived in Riverview, a once-safe Tory riding where Hatfield’s candidate had just lost a by-election to the Liberal. No one doubted that Poirier-Bastarache had helped drive the Tories of Riverview to vote against their own party.

The PC base in New Brunswick was in revolt. ...