- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Syndicate Women, sociologist Chris M. Smith uncovers a unique historical puzzle: women composed a substantial part of Chicago organized crime in the early 1900s, but during Prohibition (1920–1933), when criminal opportunities increased and crime was most profitable, women were largely excluded. During the Prohibition era, the markets for organized crime became less territorial and less specialized, and criminal organizations were restructured to require relationships with crime bosses. These processes began with, and reproduced, gender inequality. The book places organized crime within a gender-based theoretical framework while assessing patterns of relationships that have implications for non-criminal and more general societal issues around gender. As a work of criminology that draws on both historical methods and contemporary social network analysis, Syndicate Women centers the women who have been erased from analyses of gender and crime and breathes new life into our understanding of the gender gap.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Syndicate Women by Chris M. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Gender and Organized Crime

For nearly fifty years Vic Shaw, a woman of Chicago’s underworld, sold sex, booze, and narcotics. Over the course of her career Shaw rose to her prime as Chicago’s charming and beautiful “vice queen” in the early 1900s, during which time she coordinated her illicit activities with Chicago’s organized crime network and married a mobster. Not long after she reached her prime, Shaw fell to the status of Chicago’s “faded queen,” operating her brothels, drug dens, and speakeasies in isolation from organized crime and facing regular raids by law enforcement.1 Shaw’s public persona and biography are uncommonly detailed for those women of Chicago historically involved in organized crime. Yet her rise and fall paralleled the broader pattern of women’s early entrepreneurship and embeddedness in Progressive Era Chicago organized crime (1900–1919) and their near exclusion from organized crime during Prohibition (1920–1933).

As Vic Shaw told it, she arrived in Chicago as a young teenager around the time of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.2 Her real name was Emma Fitzgerald, and she had run away from her parents’ home in Nova Scotia. Her first job in Chicago was as a burlesque dancer. One night after her performance, a handsome socialite named Ebie, whose parents were Chicago millionaires, ran away with Shaw to Michigan. There, he convinced Shaw that they had gotten married.3 Ebie’s family lawyer caught up with the young couple, who were posing as newlyweds, and informed them that they were, in fact, not legally married, and that Ebie had committed a crime, as Shaw was a minor. Upon their return to Chicago, the lawyer arranged a large payout to Shaw in exchange for her leaving Ebie and his family alone.4

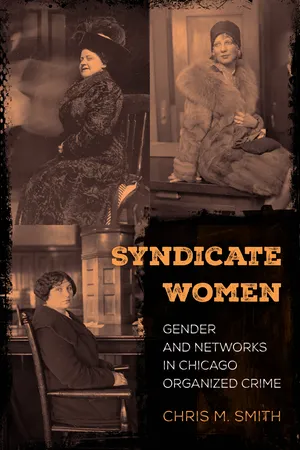

Shaw suddenly had more money than she knew what to do with, and her friends from burlesque advised her to invest in a brothel, which she did. She bought a brothel on South Dearborn Street and another on the former Armour Avenue in the late 1890s. In the beginning Shaw was not a great entrepreneur, as she was, in her words, “more interested in men than the business,” but by the turn of the twentieth century she was operating two successful luxury brothels in Chicago’s red-light district.5 She had little competition in the luxury brothel market. Shaw benefited from strong legal and political protection, arranged through her corrupt friends and organized crime associates, Aldermen Michael Kenna and John Coughlin. According to members of Chicago’s underworld, Shaw was their “queen” as her photograph from 1910 in figure 1 portrays.6 Although she entered the high-end brothel business because of her experience and personal connections in Chicago’s red-light district and the start-up capital she had received from Ebie’s lawyer, it was her connections to men of Chicago’s organized crime network that kept Shaw in business.

FIGURE 1. Vic Shaw, resort keeper associated with the Nat Moore case, in Chicago, Illinois, 1910. Source: DN-0055519, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum.

When Vic Shaw was around seventy years old, reporter Norma Lee Browning interviewed her, preserving Shaw’s reflections on her fifty-plus-year career in Chicago’s underworld.7 The Chicago Tribune published Browning’s interview with Shaw in a three-part series in 1949, just a few years before Shaw’s death.8 Browning was a brilliant reporter at a time when few women did investigative journalism, and her published interview with Shaw is a unique archival treasure.9 During their meeting, Shaw confessed her one regret in life: “‘Listen, chicken,’ she [Shaw] says philosophically, ‘I wouldn’t trade places with anybody. If I had it to do over again, I’d live every day just the same except for one thing. The only regret I have is giving up a good man like Charlie . . . to marry Roy Jones.’”10 Charlie was one of Shaw’s lovers, a hotelman who had bought Shaw her brownstone at 2906 Prairie Avenue, where she ran a brothel during Prohibition and spent her later years running a hotel for transients.11 When Shaw expressed regret over losing Charlie, she was referring to having eloped to New York City in 1907 with Roy Jones, a fellow Chicago red-light district saloon owner and brothel keeper.12 Roy Jones was the second of Shaw’s four husbands, and they were married for about seven years.13 Most likely they met in Chicago’s red-light districts, where they both ran organized crime–protected businesses. The archives do not reveal why Shaw chose Roy over Charlie.

Roy Jones became a well-established figure in organized crime during the Progressive Era in Chicago through his gambling dens, saloons, brothels, and sex-trafficking rings.14 In 1912 Jones and other prominent pimps and madams were arrested, along with more than two hundred prostitutes and clients, during a raid on the red-light district.15 Vic Shaw’s Dearborn Street brothel was the raid’s first target. There, the raiders found ten prostitutes and loaded them into a patrol wagon.16 Shaw was nowhere to be found and avoided arrest. She was not the only illicit business owner to be lucky that night.17 According to one account, the city’s “vice lords” were immediately released on bail when they arrived at the station for booking.18 The implication in this account is that they had organized crime connections that gave them immunity from formal criminal charges.

Chicago organized crime offered Roy Jones opportunities in the illicit economy during both the Progressive and Prohibition eras but eventually left Vic Shaw behind. A stark difference between Shaw’s and Jones’s organized crime careers was that during their marriage, Jones’s organized crime associations continued to grow as he developed new relationships and expanded his businesses, whereas Shaw’s organized crime relationships dissolved. She continued to draw protection benefits from organized crime, but these benefits came through Jones rather than through her own illicit businesses and direct connections to other men of organized crime.19 By 1914, around the time of Jones and Shaw’s divorce, Chicago’s underworld heralded Roy Jones as one of its “vice kings”—a moniker implying that he had usurped Shaw’s status as underworld royalty.20 In fact, within a year after the divorce, reporters were referring to Shaw as Chicago’s “faded queen.”21

Following their split, Shaw’s businesses suffered and she lacked organized crime’s protection, while Jones’s businesses continued to thrive. Shaw opened a more discreet brothel on Michigan Avenue and expanded her business into narcotics distribution. She was unable to connect her new business to the protection market coordinated by organized crime. She faced regular raids by police and morals inspectors (inspectors from Chicago’s Morals Court, which specialized in prostitution cases and other violations of morality).22 During a 1914 raid on her resort led by Morals Inspector William Dannenberg, Shaw was so enraged at the continued attacks on her businesses that she refused to leave her bed when inspectors entered her room. Instead of yielding, she waved around a revolver and threatened to shoot Dannenberg if he tried to get her. The morals inspectors simply laughed at her.23 Meanwhile, one of Jones’s apartments was cased, wiretapped, and raided in 1914 because of allegations that he was running a national sex-trafficking ring from that location.24 Investigators arrested the three men and one woman they found in the apartment, but Jones was not present and escaped arrest.25 Even with “voluminous records obtained by the stenographers,” the state was unable to prosecute Roy Jones or the other defendants.26 These two examples illustrate Shaw’s and Jones’s diverging paths in Chicago’s underworld after their divorce. Jones maintained connections to organized crime that provided legal immunity even when morals inspection raids escalated in Chicago, but Shaw did not.

The prohibition on the production, transportation, and sale of intoxicating beverages in the United States from 1920 to 1933 dramatically altered organized crime in Chicago, to the benefit of men and, as I show in the following chapters, the near exclusion of women. Only six years after their divorce, Shaw, consistent with her entrepreneurial spirit, attempted to capitalize on the evolving illicit economy. Following the introduction of Prohibition, Shaw moved her own business enterprises into bootlegging by exploiting her brothels’ underground passages to move and store booze.27 But even with her prime location in the central city, her operations were isolated from organized crime. Shaw encountered renewed police raids and faced charges of violating Prohibition laws.28 Her declining status as organized crime’s faded queen became evident when she was the victim of a $32,000 jewelry heist in 1921 and when she was fined $500 for violating Prohibition in 1928.29 Roy Jones persisted in organized crime during Prohibition, but he was less active and less connected as a nearly retired “vice king.” Jones moved to the northern suburbs of Chicago around 1923 to run the Green Parrot roadhouse for organized crime, where he appears to have continued escaping arrest and prosecution.30

The gap between Roy Jones’s and Vic Shaw’s organized crime experiences had emerged in the later years of the Progressive Era. Prohibition exacerbated their differences when Chicago organized crime mostly excluded women. Shaw’s access to women who could work in prostitution did not change, her involvement in illicit economies did not change, and her prime real estate locations in red-light districts did not change. Rather, as I show in this book, her relationships to the men of organized crime who were embedded in the restructured criminal organization changed. This restructuring dramatically altered women’s participation and position in Chicago’s organized crime syndicate. As the title of this book implies, and as I detail in the upcoming chapters, Chicago organized crime was referred to as a “syndicate” during the Progressive Era and was later called “the Syndicate” during Prohibition.

SYNDICATE WOMEN

The wives, girlfriends, relatives, and women entrepreneurs of Chicago’s gangster era are an often forgotten and hidden part of the history of organized crime. Vic Shaw’s and Roy Jones’s reputations in organized crime have not withstood the test of time as have those of “Big” Jim Colosimo, Johnny “the Fox” Torrio, Al Capone, George “Bugs” Moran, and Jack “Machine Gun” McGurn. The men of Chicago organized crime are remembered for their fashion, glamour, wealth, and violence, immortalized in celluloid and pulp fiction by the public and Hollywood’s fascination with gangster-era Chicago. Hollywood screenplays might portray a beautiful woman on a gangster’s arm in the role of mistress or “gun moll,” but she was destined to be the wailing widow by the end of his tale.31

Unlike the popular versions of this history, this book is based on years of archival research conducted in Chicago and online. I did not uncover hidden gems on gangster-era Chicago. I accessed the same archives and documents that dozens of fiction and nonfiction writers and historians have used before me, but my approach to the archives was unique. Using the tools of social network analysis and spatial analysis, I set out to plot the web of Chicago’s organized crime network and to map the illicit economy locations across the city of Chicago. I accessed thousands of pages of archival documents to find mentions of people, relationships, and addresses that were alleged to be part of the Chicago underworld. I organized all of these mentions into a database designed for the analyses presented in this book. Unlike the “gumshoes” of early 1900s Chicago, my sleuthing work in the archives relied on keyword searches, document scanners, relational spreadsheets, and closed criminal cases.

Rather than upholding the popular narrative of glamorous mobsters and their violent rivalries, this research shows that organized crime was mainly a day-to-day grind of informal, illicit, and behind-the-scenes work, in which glamor-less brewers, drivers, bouncers, saloon waitstaff, brothel madams, prostitutes, and couriers were the source of organized crime’s income-generating schemes and illicit activities.32 Infamous men—such as Colosimo, Torrio, Capone, Moran, and McGurn—and their criminal relationships shaped large sections of the organized crime network. Their criminal establishments were part of the geography of the illicit economy. However, these powerful mobsters and their positions in Chicago contrast with the ordinary men and women of organized crime around them. Women’s erasure from organized crime history has created a blind spot for the dramatic organizational change around gender and power that occurred in the early 1900s—a blind spot that, once illuminated by research, proves to be insightful for understanding the social processes through which the powerful consolidate their power, the powerless fall further into the margins, and women lose their already precarious foothold in criminal economies.

My analytical approach in Syndicate Women allowed me to trace Vic Shaw’s and Roy Jones’s connections through the same organized crime network and revealed how illicit markets, the criminal landscape of Chicago, and the structure of organized crime changed in ways that included men while increasingly excluding women. As I detail throughout the book, Prog...

Table of contents

- Subvention

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Gender and Organized Crime

- 2. Mapping Chicago’s Organized Crime and Illicit Economies

- 3. Chicago, Crime, and the Progressive Era

- 4. Syndicate Women, 1900–1919

- 5. Chicago, Crime, and Prohibition

- 6. Syndicate Women, 1920–1933

- 7. The Case for Syndicate Women

- Notes

- References

- Index