- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

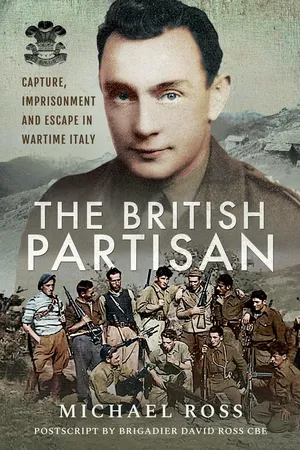

An exciting, evocative memoir of combat in North Africa, danger behind enemy lines, and two daring escapes.

In this action-packed account, a Welch Regiment officer describes his remarkable Second World War experiences. These include his baptism by fire in the Western Desert against Rommel's armor in 1942; the spontaneous help of nomad Arabs when he was on the run for ten days behind enemy lines; and his capture and life as a POW in Italy.

Michael Ross and a fellow officer made the first escape from Fontanellato POW camp only to be recaptured on the Swiss border. During his second escape, Ross fought against the occupying German forces in north Italy alongside the Italian partisans, who nearly executed him initially. He avoided recapture for over a year before finally reaching Allied lines. The reader learns of the extraordinary courage and sacrifice of local Italians helping and hiding Allied soldiers. Ross's story has a poignant conclusion as, while on the run, he fell in love with a prominent anti-fascist's daughter whom he married after the war. Originally published as From Liguria With Love, this superbly written and updated memoir is a powerful and inspiring tribute to all those who risked their lives to help him and his comrades.

In this action-packed account, a Welch Regiment officer describes his remarkable Second World War experiences. These include his baptism by fire in the Western Desert against Rommel's armor in 1942; the spontaneous help of nomad Arabs when he was on the run for ten days behind enemy lines; and his capture and life as a POW in Italy.

Michael Ross and a fellow officer made the first escape from Fontanellato POW camp only to be recaptured on the Swiss border. During his second escape, Ross fought against the occupying German forces in north Italy alongside the Italian partisans, who nearly executed him initially. He avoided recapture for over a year before finally reaching Allied lines. The reader learns of the extraordinary courage and sacrifice of local Italians helping and hiding Allied soldiers. Ross's story has a poignant conclusion as, while on the run, he fell in love with a prominent anti-fascist's daughter whom he married after the war. Originally published as From Liguria With Love, this superbly written and updated memoir is a powerful and inspiring tribute to all those who risked their lives to help him and his comrades.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The British Partisan by Michael Ross in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

A Soldier

Chapter 1

Despatch to a Desert Fort

It was Christmas Day 1941, with the Eighth Army somewhere in the Libyan desert. There had been a long pause in hostilities, and on a clear sunny morning in the presence of a small group of men in my company, fellow Catholics, I held a short service of prayer. I read the gospel of the Nativity – we were not far removed from the site of the original – yet somehow it all seemed a bit out of place. The men listened in silence; at least on that day it was a link with home.

We had reason to give thanks, for in under two months the Eighth Army had driven the German-Italian forces deep into Libya and lifted the threat to Egypt, our main base. One third of the country was back in our hands. Our gains included the large port of Benghazi, and it was to this place that our battalion of the Welch Regiment, with others, had received orders to proceed.

We did not baulk at this. In place of tents and bivouacs, we were back to barrack huts, iron bedsteads and running water. Less popularly, however, we were also back to tiresome training schedules. But it proved to be brief.

By 15 January we were on the move once more. Our destination was Fort Sceleidima, an uninhabited location in the open desert 50 miles south of Benghazi. Our orders were to occupy the place and hold it.

It lay in the now wide expanse of no-man’s-land which had been opened up by the enemy’s rapid retreat westwards. At Sceleidima we would be among the forward elements of the Eighth Army. We estimated the main body of the enemy to be 100 miles or so away. In desert conditions, however, that distance could be covered in a few hours.

Although the disengagement of the enemy had been forced upon them by their recent defeats, the campaign had taken its toll on us too. The fact that we had given up the chase suggested that we were stretched to the limit and in need of reinforcements. The enemy, though, had always to be kept guessing, and probing missions of the kind in which we were now engaged might serve to confuse them.

* * *

We left Benghazi on a sunny morning in a long convoy of vehicles under command of Colonel Napier, our battalion CO. We numbered about 400 men, some 200 having been left behind on garrison duties. Escorting the convoy was an anti-tank company commanded by me, consisting of nine guns each mounted on its own motor vehicle called a portee. These guns would be the convoy’s only protection against attack by enemy armoured units as we had no tanks in close support.

Once clear of Benghazi we were on to the rough, dusty surface of the desert. Away to the east, on our left, was a high escarpment rising above the surrounding desert. This was the perimeter of a fertile region lying behind it called the Jebel Akhdar (The Green Mountain).

This escarpment ran due south for some 50 miles. It was cliff-like in parts and terminated at the extreme southern corner of the plateau. According to our maps, it was at this point that our objective, Sceleidima, was to be found. Beyond it was only desert.

The navigating officer steered the convoy towards this feature. On reaching it we picked up a firm, well-worn track winding its way due south along the foot of this high ground.

Our convoy laboured cautiously along this track skirting the escarpment towering above us on our left. On our right lay the open desert stretching as far as the eye could see, shimmering and gleaming.

My nine gun portees drove in single column on the right flank of the convoy of vehicles, keeping parallel to it. It was on this open side that any encounter with the enemy was likely to occur. We were venturing into no-man’s-land, so a strict watch was kept for signs of anything unusual. I was in the leading portee and halted the jolting vehicle from time to time to gaze long and hard through my binoculars at the horizon. A low cloud of dust would have betrayed enemy movement, but none appeared, and by late afternoon on a warm, cloudless day we reached the fort without incident.

* * *

Of the fort itself there were few traces – a broken tower or two and some crumbling walls. Centuries before, it had been an outpost of the Roman and Islamic empires. It was easy to see why this site had been chosen: it was perched in an elevated position on the extreme corner of the plateau with uninterrupted views of the approaches across the lower-lying desert to the south and west.

Behind the fort the Jebel Akhdar stretched 50 miles north to the Mediterranean coast and 100 miles east before meeting the desert again. Resembling a hilly island in a sea of sand, it comprised an area of bush and scrub with grass and trees in its more fertile parts, and was the homeland of wandering Senussi tribes.

Beyond the horizon to our front, somewhere in the open expanses, mobile columns of the Guards Armoured Brigade were known to be operating. This was some comfort to us as we were conscious of being probably the nearest ground troops to the main body of the enemy.

After arrival we followed the usual routine of orders and briefings, posting of sentries, despatch of patrols, selection of firing positions, digging of protective trenches and unloading of stores. My first task was the offloading of the guns and siting them around the front of the fort. Then came the domestic chores, dispersal of the men in bivouac areas, digging of latrines and preparation of meals. Every moment of what was left of daylight was spent in improving our camouflage and acquainting ourselves with the layout of the area, before settling down to the first night’s vigil.

* * *

It proved a peaceful night, and when dawn came we resumed the task of building our defences. Patrolling the danger zone continued day and night but resulted invariably in ‘Nothing to report’. The days passed, but the situation remained unchanged.

Morale, however, was still high. Men had long since felt a special pride in belonging to the Eighth Army and perhaps even a touch of romanticism about campaigning in the desert.

Unlike the battles waged through densely populated Europe in 1940, with their aftermath of human misery, those in North Africa had been fought over vast empty stretches of desert wastes devoid of habitation. Such terrain, lacking roads, shelter and water, was neutral; there was no third human element to help or hinder the combatants.

These were times when the leaders of both sides enforced strict codes of conduct and discipline, reflected in the humane treatment of prisoners and especially of the wounded. The enemy was spoken of in respectful terms. The shrewdness of Rommel and the skill at arms of his soldiers were fully acknowledged. Rommel himself had become a legend – it was customary for us to refer to the enemy simply as ‘Rommel’, something our High Command thought fit expressly to forbid, albeit in vain.

Identification with the enemy was not surprising; men on both sides were in a strange landscape far removed from home; loneliness and isolation were felt by friend and foe alike; we endured the same hardships of life in a barren desert, as well as sharing the joys of its occasional beauty.

Comparison could be drawn with the fellowship evidenced among the combatants on the Western Front of the First World War: those men lived and died in a unique world known only to themselves. Jon’s cartoons of the Eighth Army’s ‘Two Types’ in Libya shared a kindred spirit with Bruce Bainsfather’s ‘Ole Bill’ in Flanders a quarter of a century earlier.

The battle zone was itself confined within clearly defined boundaries, the sea to the north, the forbidding soft sands to the south, whilst to the east and west lay the safe base areas, ours at Cairo and the Axis’s at Tripoli. These bases were like havens, essential to the preparation and launching of offensives, just as seaports were to the conduct of naval operations. In both cases, the further one ventured from them the greater the problems of supply, communications and security.

There were many ways in which conditions in the desert bore resemblance to those on the high seas. Landmarks were few or negligible, making navigation by compass common. The vagaries of the elements could bear as hard upon the desert soldier as on the sailor. Sandstorms, reducing visibility to zero, could blow up suddenly and, like gales or fog at sea, curtail activity for days on end. Soldiers hated them; the fine dust stuck to their faces like brown make-up, while the grit penetrated everything, including food and drink.

Desert fighting units, like warships, had to be mobile and self-contained. In between planned offensives there were periods when contact with the enemy could be lost altogether, and if chance encounters occurred they were usually short and sharp. The small, specially equipped units of our Long Range Desert Group would embark on missions deep into enemy territory, make surprise attacks on selected targets, submarine-fashion, then hasten back to base, relying on speed and camouflage to outwit and escape the enemy.

This analogy between sea and desert warfare held good in the field of strategy. The mere acquisition and occupation of desert lands, like parts of the ocean, could be meaningless. Indeed, it could be an unwanted liability. Both sides had long since learned that ultimate victory would go to the one that succeeded in trapping the opposing forces and capturing or destroying them. Only then could the war in North Africa be brought to an end and the territories permanently secured.

Chapter 2

Enemy Threats

It was a week since we had taken up positions around the fort. Life had been peaceful, and the silence was broken only by occasional distant explosions, no doubt the work of hit-and-run aircraft raiding supply lines. Nevertheless, vigilance was essential and sentries kept continuous watch round the clock. The enemy on the ground was still remote and unseen, but one morning we received a sharp reminder that he was indeed there, lurking just beyond our horizon. It was an incident involving two of our Bren gun carriers. These were small, fast, tracked vehicles with some armour plating, but open on top. They carried four or five men and were very suitable for reconnaissance missions. A pair of them was sent out every day to probe the area well ahead of our position.

One morning when far afield, they suddenly encountered two enemy light tanks and came under fire from their cannon. The carriers, armed only with machine guns, wisely sought to escape as quickly as possible. The enemy gave chase and during the skirmish one of the carriers was halted by a direct hit. The second carrier was unable to go to its assistance as the tanks were closing in on it. On reaching the stricken carrier, the enemy gave up the pursuit, presumably deciding they had ventured far enough. This enabled our second carrier to get back safely and tell the tale.

It was during the hours of darkness, however, that the enemy would bestir himself like some nocturnal animal awakening and make his presence known. The blackness of the sky would frequently be disturbed by distant ground flashes illuminating temporarily the cloud formations above. Occasionally an aircraft would be seen to ignite in the sky and fall slowly and silently with a trail of fire.

More common was the sight of a succession of coloured signal lights which the enemy would shoot up into the sky at regular intervals as markers for their mobile columns. The movement of these roving columns could be easily followed by the changing position of the lights. It was difficult to judge how far away they were, but at times they seemed to be advancing well into our territory and, more disconcertingly, on all sides. The dawn, however, would reveal no trace of these nightly apparitions.

By contrast, the daylight hours passed uneventfully and we busied ourselves digging and camouflaging and generally making ourselves more secure and comfortable. As usual during times of inactivity, there was much speculation about the immediate future. Conflicting rumours spread among the soldiery which, we used to say, was a pretty sure indicator that Army Headquarters was uncertain about the next move too. Private Thomas, my batman, was convinced that Richie, the Eighth Army commander, was all for pressing on, while Auchinleck, the overall commander in the Middle East, favoured a period of consolidation. Dai Morgan, the company cook, had been assured by an RASC corporal delivering the rations that the Welch were to be taken out of the line and sent back to Alexandria for garrison duties – the soldier’s pipe dream. But whatever the options, a big decision was imminent, as we learned that Auchinleck had just flown up to Benghazi to confer with Richie.

The conjecture and speculation, however, were soon set aside when suddenly and quite unexpectedly we came face to face with the realities of the situation.

* * *

It happened one hot afternoon when a lookout, peering through the haze with his binoculars, sighted a solitary figure far off in the open desert staggering about aimlessly. A section of men was sent out to investigate.

It turned out to be a British officer, a major of the Queen’s Bays, so mentally and physically exhausted that he had to be helped back to our lines. He was tall, slightly built, with fair hair but balding; not a young man. His features were drawn and his eyes lifeless, a victim of shock.

Later that evening, after he had slept, he took some food in our mess vehicle. We were naturally eager to ply him with questions, but his responses were slow and laboured and it was not easy to make sense of what he mumbled. Apparently his armoured squadron had been engaged by the enemy and his own tank had been hit and set on fire. He managed to extricate himself but was the only one of his crew to survive. He had been wandering for two days so was lucky to have stumbled upon our detachment. I do not think he could have gone much further.

From what else he said one thing became clear: our tanks had been engaged in large numbers and had suffered a serious defeat. This was our first inkling of the crucial events of the previous few days. Only later were we to hear the whole story.

We learned that between 23 and 25 January a trial of strength between the armoured forces of both sides had taken place. The German Panzer Division, with its acknowledged superiority in armoured fighting vehicles, was involved in a number of widespread encounters with British mobile units, including the newly arrived and inexperienced 1 Armoured Division.

There had been much confusion and differences of opinion between the British commanders regarding the best course of action to be taken. The ensuing indecision and delays had been quickly seized upon by Rommel and used to his advantage. The result had been a series of crippling defeats for our forward armoured units. The loss of tanks was critical; they are the teeth of an army. Just as an animal without teeth cannot long survive in the jungle, so an army without tanks cannot hope to do so in battle.

Perhaps this state of confusion was to blame for some contradictory orders that we had ourselves received the day before the arrival of the fugitive tank officer. We were told to pull back immediately to Regima, a town some 50 miles to the north in the Jebel Akhdar region. So we packed up and left, but when only half way we received countermanding orders telling us to get straight back to Sceleidima.

The facts gleaned at first hand from our visitor provided a realistic if cheerless assessment of the situation. He left us in a returning ration truck after a night’s rest, but the ill tidings he had brought remained with us. There seemed little prospect now of the much vaunted spring offensive by the Eighth Army. Rommel had grasped the initiative, and the chances were that we would be obliged to stay put and wait for the enemy storm to break upon us.

Ominous signs of what was in store were soon forthcoming. Late that afternoon, towards the east, came the sound of unusually heavy explosions. They continued after dark so we were able to time the interval between the flash and the boom – the sort of thing one did as a child during thunderstorms. From this we calculated them to be 30 miles away at a place we judged must be Msus.

Msus was one of our manned outposts guarding a forward petrol and ammunition dump. We could only conclude that either the enemy was attacking the place or else our sappers were deliberately blowing up the dump to prevent it falling into enemy hands Whatever was going on, there could be no doubt now that Rommel was on the move.

* * *

After a day of intermittent rain and grey haze, dawn on the 27 th was bright. The clouds had dispersed, leaving a clear sky and crisp air. A mid-morning bucket of tea had just arrived from the company cookhouse and was being ladled into the dixies of the waiting soldiers. The usual exchange of views on the quality of the brew followed. Occasionally it would be salty, more frequentl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps and Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I: A Soldier

- Part II: A Prisoner

- Part III: A Lame Dog

- Postscript

- Plate section