- 592 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

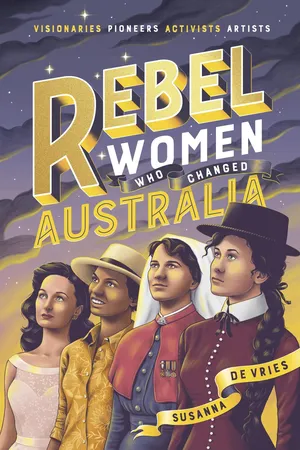

Rebel Women Who Changed Australia

About this book

Visionaries, pioneers, activists and artists - women who made a difference to Australia

An updated and condensed edition of Susanna de Vries' Great Australian Women, this is a celebration of women who broke the mould, crashed through the ceilings, and shaped the nation in the fields of medicine, law, the arts and politics.

From Lillie Goodisson, pioneer of family planning, to Eileen Joyce, world-famous pianist, Enid Lyons, our first female cabinet minister, Stella Miles Franklin, who endowed our most celebrated literary prize, and Catherine Hamlin, who has given hope to thousands of women through her fistula hospitals in Africa, these are women who have made a difference. They are the women who helped to forge the Australia we know today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rebel Women Who Changed Australia by Susanna De Vries in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ART, MUSIC, LITERATURE AND SPORT

CHAPTER TEN

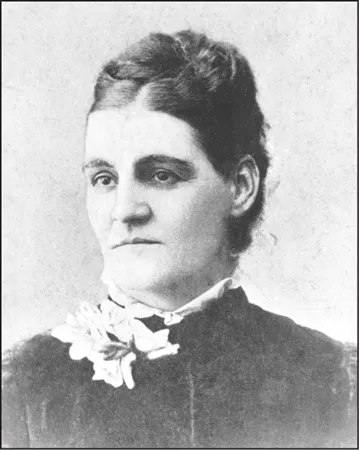

Louisa Lawson

(1848–1920)

Mary Gilmore

(1865–1962)

POETS/JOURNALISTS WHO CHAMPIONED THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN AND THE DISADVANTAGED

Louisa Lawson and Mary Gilmore had a great deal in common: they both tried to improve the lot of women, the poor and the disadvantaged. They both experienced unsatisfactory marriages. Yet what started out as friendship between an older writer and a younger one (Mary was seventeen years younger than Louisa) turned into mutual loathing and a bitter feud. As Louisa Lawson’s star waned, that of Mary Gilmore ascended. Louisa Lawson went to a pauper’s grave, unmourned and friendless: four decades later Mary Gilmore, having achieved literary fame, would be mourned by hundreds and given a State funeral.

Louisa was born into rural poverty. Her father, Henry Albury, attempted various occupations without success before running a shanty pub. Her mother, Harriet, English-born daughter of a Methodist minister, was embittered by her husband’s financial failures. She insisted on removing Louisa from school at thirteen, even though the young girl always had her head in a book and dreamed of becoming a teacher. Louisa would always yearn after the literary glory she never achieved.

Both women had tough bush childhoods which formed their characters. Mary Ann Cameron was born in a slab hut near Goulburn belonging to her maternal grandfather. Her first years were spent surrounded by gum trees and wattles; she would love the land with a passion all her life. She came from a long line of clever, talented Orangemen and Scottish crofters. Her father eventually became a building contractor and travelled all over outback New South Wales and southern Queensland in search of work.1 Sitting beside him on the horse-drawn wagon, or on the front of his saddle as he rode, at the age of five, Mary learned at first-hand about the hardships endured by settlers, drovers and teamsters, and their ruthlessness towards the Aborigines, with whom she sometimes played. (Her father became a ‘blood brother’ of the Waradgery tribe). During her childhood, Mary absorbed a store of experiences which would surface decades later in her book Old Days, Old Ways, in which she wrote about rural poverty, families whose children lived on damper and treacle and the odd roast possum leg, and the hardships of the bush.

Unlike Louisa Albury’s poverty-stricken family in which no one valued education, Mary Cameron’s father encouraged her to read and to become a pupil-teacher in a tiny bush school at Cootamundra, run by one of her uncles. By the age of twelve, she was fluent in ancient Greek and Latin.

Louisa Albury, also highly intelligent, did not study Greek but was taught at school to appreciate and write poetry. She too wanted to become a pupil-teacher, but instead she had to leave school at thirteen. Although her father was practically illiterate, he had a tremendous gift for storytelling which both Louisa and her eldest son would inherit.

Louisa shared Mary’s sympathy for the poor and disadvantaged: like Mary, she had lived among them. Louisa was the eldest daughter in a family of nine surviving children. While Mary’s mother encouraged her daughter to read and study, Harriet Albury bitterly resented her eldest daughter’s love of learning and her passion for poetry. She burned her daughter’s first poems as well as some of her favourite books. Louisa never forgave her. Her mother also deplored what she regarded as Louisa’s radical ideas, and forced her to look after her younger siblings and do housework.

Louisa’s father, basically a kind man, had a weakness for alcohol. Like Mary Cameron’s father he became a small-time builder but failed dismally. After his only horse broke its neck pulling an overloaded cart across a creek, Henry Albury consoled himself with drink. Too poor to buy another horse, he stopped working altogether. There was no unemployment benefit, and Louisa and her siblings were reduced to begging or fossicking the local mullock heaps for specks of gold, until finally her father opened a shanty pub.

Surrounded by insecurity, stress and poverty, Louisa and her mother argued constantly. Domestic service in the city would have presented one avenue of escape for Louisa, but her mother refused to let her seek work in the city. Louisa bitterly resented her life of drudgery; marriage to anyone at all was the only way left to escape from her nagging mother.

Henry Albury’s general store and pub catered for rough, rowdy goldminers. To attract customers, her father encouraged Louisa, who had a fine voice, to sing in the bar. The miners enjoyed Louisa’s singing and suggested that they should pass round the hat to collect money so that she could have her voice trained. But Louisa’s mother also prevented her daughter from taking this opportunity to make something of her life.

Louisa’s spirit was unquenchable: she dreamed of becoming a writer and being involved in the world of books. Her father’s drinking bouts and her mother’s nagging prompted her to seek escape by making a hasty marriage to a man obsessed by the idea of finding gold. At eighteen, Louisa was a relatively unsophisticated but attractive bush girl. After yet another row with her mother, Louisa was sitting crying in the bush when she was consoled by a sturdy bearded gold prospector named Niels Larsen. Larsen, born in Norway, was a sailor who had jumped ship in order to join the gold rush in Australia.

Niels was not Louisa’s first suitor. Decades later, she would dedicate some beautiful poems on love and loss to a man she did not marry, for reasons which remain unclear. All we do know is that on 7 July 1866, tall, statuesque auburn-haired Louisa walked to the Wesleyan church in Mudgee to marry a man almost twice her age whom she scarcely knew.2 Niels Larsen was kind-hearted and generous, but if his temper was roused and he had been drinking, he could become physically violent, something Louisa failed to realise when she accepted his proposal. Niels Larsen’s lack of education was in sharp contrast to Louisa’s hopes for a career of her own. She married in haste and repented at leisure – although lack of money would ensure she enjoyed little leisure for the rest of her life.

Accounts differ as to how Niels Larsen became ‘Peter Lawson’. Either at their wedding or at her eldest son’s christening, the officiating minister ‘Australianised’ his name.

Louisa joined her husband in his tent on the diggings. In spite of months of backbreaking labour he failed to find gold. Soon Louisa, to her dismay, found she was pregnant. They had no income, no savings, no furniture and not enough money to pay for a doctor to deliver her baby.

Legend has it that Louisa’s first son, the future poet Henry Lawson, was born in a tent on the Grenfell goldfields. The birth was difficult. Louisa had post-natal complications known then as ‘milk fever’, which made breast-feeding extremely painful.3 Bringing up a baby in a tent in the muddy goldfields, having to cart all drinking and washing water by hand from the nearest creek and boil it, and having little money for food proved stressful and exhausting for Louisa.

The Lawsons and their baby son moved from goldfield to goldfield living in various squalid, fly-ridden, cockroach-infested slab huts and shanties, blazing hot in summer, and cold in winter, when the wind blew in gusts through the gaps between the roughly cut slabs. Meanwhile, Peter Lawson’s constant search for gold yielded virtually nothing.

When Louisa fell pregnant once more Peter Lawson finally listened to his wife’s pleas and became a selector, buying a small block of land on a low-interest mortgage. Lacking any capital, the Lawsons had no choice but to take whatever land was allotted to them, however harsh. Wealthy squatters had usually tied up all the best land and the waterholes. Louisa exchanged life in a tent for life in what was virtually a shack, surrounded by rural squalor and poverty on forty acres at Eurunderee, near Mudgee (then known as New Pipeclay). Louisa’s husband chose this area because it was part of the goldfields; he hoped some small pocket of undiscovered gold might remain on this scarred land, pitted with trenches from previous mining. Most of the trees had been cut down to build pit props and shafts. Their little wooden house had a dirt floor, and no piped water or sanitation. Louisa cooked over a wood stove which provided heating in winter. Their furniture was made from packing crates; their diet consisted of bread and dripping, treacle and salt beef.

Louisa, like all women of this period, which viewed women’s role as bearing child after child, lacked access to reliable contraceptive advice. All she had were old wives’ remedies which failed. Under these extremely squalid living conditions she soon bore her husband two more sons.

Her third pregnancy and birth proved difficult and dangerous. For months after her child was born she could not sleep at night, dozing off for only short periods, and had no desire to eat. Almost anorexic, trying unsuccessfully to breastfeed, the normally hardworking Louisa would sit motionless for hours on end, crying to herself and rocking backwards and forwards while baby Peter howled and Charlie and Henry fended for themselves. This period of mute inactivity exasperated her husband. At that time no one knew anything about the dangerous and distressing hormonal disturbance we now call postnatal depression. There were no antidepressant drugs to treat Louisa’s condition. Some women who suffered from it would fill their pockets with stones and jump into the dam, but Louisa resisted the temptation to commit suicide. Still devout and religious, she found comfort in prayer. As her sons grew older and were less work, she recovered – but throughout her life bouts of depressive illness would recurr when she was under extreme stress, and her postnatal depressions coloured her view of sex and child-rearing.

She was now able to take over the running of the property again and drive their horses into town to buy provisions. Horses held no fear for her: on one occasion she halted and subdued a team of bolting horses, an incident Henry Lawson would later recount in a short story.

Peter Lawson spent a great deal of time away from home, chasing his dream of finding gold, which for him was a true gambling addiction. It finally became obvious that the proceeds from farming their small selection were as negligible as those from his gold-prospecting, and Peter decided to work with Louisa’s father as an unskilled ‘humpy’ builder. Lacking any transport he had to walk to distant building sites and camp there overnight. This meant that most of the farm work was thrown onto Louisa’s shoulders.

When he did return home, Peter worked hard on digging the unyielding soil of their selection and over the course of a year constructed a large dam. To earn more money Louisa took in sewing in addition to looking after the children, cleaning the house, cooking the meals and doing the washing. She also milked the cows night and morning, sold milk and butter, helped to harvest hay and fattened the calves, bottlefeeding those that were sickly. The strain of hard physical work and the constant money worries took their toll in blinding headaches and renewed attacks of depression.4 Her only escape lay in writing poetry and reading favourite poems aloud from her old schoolbooks.

Louisa did not want any more children until they could afford to rear them. At that time a husband ‘owned’ his wife’s body; she could not by law deny him ‘conjugal rights’. The only form of contraception available to Louisa was coitus interruptus.5 She was soon pregnant once again, following physical violence when she had sought to resist her husband. In later life she would describe married bedrooms as ‘chambers of horror’. The same sad drama was played out all over the bush by women reluctant to bear children and their husbands: at this time many bush women commonly bore six to sixteen children, many of whom died young.

After another difficult pregnancy, Louisa gave birth to twins, Gertrude and Annette. The Lawson babies became the marvel of the district, the first twins to be born in Eurunderee. Annette was fair, plump and placid; Gertrude dark, bad-tempered and grizzly. Louisa adored Annette and called her ‘a golden child’.

One day in January 1878, while Peter was away from home, Annette ran a high fever. Louisa harnessed the horses and drove her fretful baby to the hospital at Mudgee where she had given birth to the twins. Sick with terror, she waited in the passage outside the ward until the nurses told her there was nothing more they could do. Annette, her ‘golden child’ was dead. Another depression followed; once more Louisa could neither sleep nor eat. It was feared that she might die. Her mother was summoned and reluctantly arrived to care for the three boys and little Gertrude. The only advice Louisa received was provided by her unsympathetic mother, who told her it was high time she ‘pulled herself together’.

Louisa turned to writing poems to relieve her misery. She sat at the rickety table and wrote a moving poem, ‘My Nettie’, dedicated to the memory of Annette. It was later published in the Mudgee Independent. Other poems followed, including ‘Mary! Pity Women’, describing a mother’s desperate journey on foot with a sick baby to a doctor, in which the baby dies en route. These were followed by other verses about lonely, depressed bushwomen, based on her own experiences.

Louisa had a talent for writing poetry but she was a working-class woman who had been denied education: she would never have the time or leisure to develop her talent to its full extent. In spite of their back-breaking years of toil and drudgery, Peter and Louisa Lawson never managed to achieve even a modicum of financial security. It was a fate from which Louisa attempted to escape in vain.

When Henry was eight, Louisa realised he was exceptionally talented and sensitive, a child apart. She was desperate that somehow Henry should receive the education she had been denied and a chance to escape rural poverty. The nearest bush school was over five kilometres away; Henry was a sickly child and she feared he could not manage the walk. Louisa campaigned fiercely for a school to be built in their own area, but as she was ‘only a woman’ she was not allowed to enter a public meeting about it, although she had organised it. She was told that the subject of a school could only be discussed by men, and was forced to stand outside the hall and attempt to hear her own arguments poorly presented to the meeting by her husband. This experience taught Louisa a lesson about women’s lack of power she would never forget.

Eventually the campaign she had originated did succeed and a tiny bush school opened at Eurunderee. Henry was one of the first pupils, but at the age of nine he suffered an unknown fever which left him near death, and caused him to miss a great deal of schooling. By the time he turned fourteen he had suffered major hearing loss. A diffident and withdrawn boy, he aimed to become a writer. Louisa encouraged him and gave him what little extra schooling she could.

Her second child, Charlie, had severe personality problems and a t...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction – The Changing Role of Australian Women

- Medicine and Nursing

- Law and Politics

- Art, Music, Literature and Sport

- Philanthropists and Humanitarians

- Endnotes

- About the Author

- Books by Susanna de Vries

- Copyright