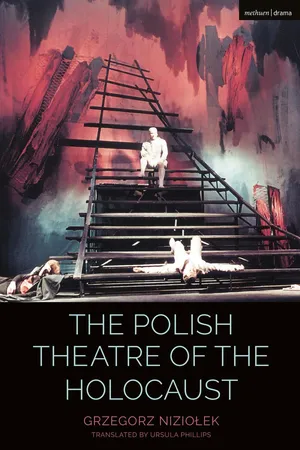

![]()

PART ONE

The Holocaust and the theatre

![]()

1

The theatre of gapers

1.

‘Around noon that day numerous passers-by on Aleje Jerozolimskie indicated to one another with a glance or with their fingers a man who had aroused general excitement on the street.’1 On a sweltering July day in 1943, Jakub Gold, the protagonist of Kazimierz Brandys’s novel Samson (1948), is driven by fear from his hiding place in a cellar, where he had lived for several months in darkness. By that time, as Brandys scrupulously notes, Warsaw had already been ‘cleansed of Jews’. The sight on the street in the bright light of day of this dark, filthy, emaciated figure therefore arouses all the more excitement and curiosity. Someone spits at him, someone laughs, someone hurls an insulting word. Someone else expresses helpless compassion. At first, they don’t all recognize him as a Jew, thinking he is perhaps blind or a madman. But Jakub is aware of everything: dazzled by the sunlight and feeling bewildered, like an actor pushed onto a stage, he does not see his audience, although he naturally senses its aggressive presence. Brandys portrays various reactions of the passers-by, as if he were an omniscient narrator knowing the secrets of this momentarily enlivened crowd, although he really identifies with Jakub, paralysed by fear and incapable of observing his surroundings. The community of onlookers united by their exchange of looks and gestures is a great enigma not only to Jakub.

Brandys wrote his novel immediately after the war, exposing and recording a situation in which to Polish passers-by, Jewish suffering was purely a spectacle taking place beyond an invisible, impassable boundary line and affecting beings who had already been excluded from the human community and left to their ‘fate’. The real event already appears within a framework of theatricality, which tries to justify the indifference and shameful behaviour of the ‘spectators’.

FIGURES 1.1–1.12 Frames from Andrzej Wajda’s film Samson. Production: Zespół Filmowy Droga, Studio Filmowe Kadr, Wytwórnia Filmów Fabularnych, Łódź. Poland, 1961.

Were we to refer to the famous example of the Street Scene as the most basic model of epic theatre, as analysed by Bertolt Brecht (1950),2 everything in our case would have to be reversed. There is no one who could explain to the audience – like Brecht’s zealous narrator – the sense of the street incident. Reconstruct it and analyse it. However, in this case, the ‘sense’ is clear to everyone, as is the inevitable fate of the Jew driven onto the street by fear. The true mystery here remains the audience, united by a wave of shared energy, a secret code of understanding, the conspiracy of distance. The audience is as if divided, diverse in its reactions, yet at the same time united, animated (not to say – roused), bound by a common impulse. This precise scene will remain long in the collective memory as a situation devoid of explanatory meta-commentary, uninscribed into any narrative order, left to the law of unconscious repetition, and therefore seized upon by theatre. Brecht, in constructing his model of the street scene, accepted several self-evident assumptions. First: the street scene is the repetition – within the framework of a consciously constructed dramaturgy – of something that happened a moment ago. Second: the narrator has clearly seen the event, has at his disposal analytical tools (for example, class consciousness) capable of illuminating the causes of the incident, and manages to distance himself from his own ‘experiences’ as a witness. Third: the audience is innocent; therefore, the circumstances in which the spectators, fearful maybe of being accused of participation, might have had an interest in the truth about the incident remaining concealed, are not taken into consideration. In the case of the street incident described by Brandys, we cannot apply these assumptions. It cannot therefore be repeated according to Brecht’s prescription.

Raul Hilberg expressed the experience of the Holocaust in terms closely related to the phenomenology of spectacle, defining the three main positions of active and passive participants as those of perpetrators, victims and bystanders. He tried to establish the extent of their awareness as well as – most importantly – the degree to which events were visible at the time of the persecution and extermination of Jews. The most hidden participants were the perpetrators, the most visible – the victims: ‘the victims were perpetually exposed. They were identifiable and countable at every turn.’3 The scene from Brandys’s novel confirms Hilberg’s observations. There are no obvious perpetrators, while the victim is clearly visible, though he himself has difficulty seeing. Exposing the fact of visibility points in turn to the inescapable presence of witnesses. The invisibility of the perpetrators, on the other hand, allows for various ways in which the incident may be ‘sacralized’, inscribed into systems of necessity, destiny, human helplessness, in relation to ‘higher powers’. The matrix of ‘tragedy’ emerges of its own accord. ‘The Lord God Himself didn’t help, but you would have liked to,’ a woman is told when she expresses her timid and feeble desire to help Jakub,4 to include him in so doing in the community of spectators, and thereby violate the ‘tragic’ theatricality of the entire incident. Within the confines of the described situation, Brandys carries out a stage director’s radical intervention: he allows an audience to be seen, including its libidinal engagement in the creation of attitudes of indifference and hostility.

Easy disruption of ties with an excluded and persecuted person brings with it a series of consequences. When it is impossible to gain physical distance from the watched sufferings, a psychological distance appears. As Cynthia Ozick explains in her text on the ‘ordinary’ observers of the Holocaust, ‘indifference is not so much a gesture of looking away – of choosing to be passive – as it is an active disinclination to feel’.5 The perpetrators expect the ‘bystanders’ to go on leading ‘normal’ lives, and so the latter have to work out a series of self-justifications, so as not to perceive themselves as the ones who refused help.6 Going on living according to previously held ethical and social principles inevitably acquires aspects of theatricality: abiding by former standards alters their sense, and becomes a strategy for performing forgetfulness, not only for performing community. By the same token, the bystanders cease to be reliable witnesses to the events which they have seen. They are no longer spectators but have become actors.

In using the word ‘witness’, Hilberg has in mind the passive observer; therefore, he employs the designation bystander and not witness. ‘Bystander’ describes more precisely the position of the passive witness, and even evaluates it morally. A ‘witness’, on the other hand, could also be a victim or a perpetrator.

Or – according to more radical formulations – there are no witnesses at all to the Holocaust,7 because a traumatic event of this kind is based on the loss of experience, leaving in its wake the impossibility of coming to terms with reality through the act of bearing witness. Loss of any stable knowledge for understanding the event in which one is a participant also encompasses the bystanders. The attempt to precisely define and separate the three positions can therefore lead to their surprising intermixing – or rather standardization – in a common feeling of loss of reality linked to the trauma. Clear distribution of roles, even though this may seem historically unproblematic and ethically correct (if only as an answer to the Nazi legislation that sought to identify as precisely as possible victims for persecution and extermination), constantly comes up against the barriers created by the very act of bearing witness to past events.

Hilberg himself confirms this in the afterword to the Polish translation of his book: ‘In the years 1933–1945 perpetrators, victims and bystanders made up separate groups, and each one of them perceived events from their own perspective, playing their own appropriate role in them. However, despite all the differences that divided them, their experiences and behaviour had certain features in common.’8 In the first place, Hilberg mentions incomplete knowledge of the events in which all sides were involved. The incomplete knowledge that Hilberg writes about does not necessarily overlap, however, with the loss of experience indicated by researchers of trauma. The first of these phenomena should be located within the discourse of history, the second in the discourse of memory. This does not mean, however, that they have to be mutually exclusive: loss of experience can produce the impression of incomplete knowledge, while incomplete knowledge can intensify or weaken the traumatic loss of experience. In the case of the position of the bystanders, however, we cannot overlook the fact of their generally over-eager reconciliation to the inevitability of what is going on.

From this moment on, history becomes negative history – not an account of heroic deeds but a virtual stage of deeds not undertaken. Michael R. Marrus calls the history of the Holocaust, a history of ‘inaction, indifference, insensitivity’.9 Knowing that people ought to have behaved otherwise does not entitle us, however, so Marrus claims, to morally evaluate them, but rather to analyse their states of mind.

2.

In the 1990s, Feliks Tych researched a large collection of Polish diaries and memoirs of the Second World War looking for evidence of the Holocaust. Tych tried to recover in them the experience of Polish witnesses. The material proved to be highly diverse, but one conclusion emerges most strongly from his reflections:

Were we to ask what dominates in the texts I have read, then the answer would have to be, from the point of view of our analysis, that the dominant thing is what is not there. The authors of the majority of the analysed texts either made no note of the phenomenon of the Holocaust, or they did not perceive its civilizational exceptionality. For some, it was merely an episode. Many did realize, however, that they were confronting an exceptional crime, totally alien to the civilization in which they had grown up and its moral canons.10

Following on from Tych’s conclusions, one could risk the assertion, crucial to my own reflections, that eagerness not to accept the position of observer, to deny it, became the strongest experience of Polish witnesses to the Holocaust – if, of course, we accept that it was an event sufficiently visible to Polish society; for Tych, there was no question about this. Feliks Tych is naturally aware of the various reasons behind this eloquent and dominant fact of the inadequate recording of the Holocaust in Polish written testimonies: ‘sometimes it is fear that the text would be discovered by the Germans, sometimes an expression of helplessness, sometimes a symptom of indifference, sometimes self-defence against fully admitting to oneself the enormity of the crime committed against Jews.’11 Among the reactions to the Holocaust recorded in diaries and memoirs, the most typical is dismay at one’s own helplessness; on the other hand, according to Tych, the attitudes most passed over in silence were, for obvious reasons, those of open hostility towards the victims. Despite this, it is possible to reconstruct from the written testimonies a characteristic mechanism of mounting aggression on the part of the observers towards the victims as the persecutions intensified. This aggression was a result of the breaking of ties of empathy with the victims, becoming the order of the day and enabling one to disregard one’s own helplessness and actively justify it.

‘We will probably never find out, in how many cases the disappearance of the Jewish theme from a large number of wartime memoirs resulted from complete indifference to the Jewish fate, and in how many from a desire to stifle some traumatic experience, or from moral discomfort.’12 Even if we have to resign ourselves to the unresolvability of this conclusion, it indicates clear limitations to applying the methodology of research on trauma to accounts of the experience of Polish witnesses to the Holocaust. This is particularly the case since we must take into consideration also the potential indifference of Polish society.

It is difficult, however, to definitively resolve whether the fact of watching someone else’s suffering – in forms so extreme and before then unknown in the experience of the observers – was subject to the phenomenon of traumatic paralysis. Lawrence L. Langer includes among testimonies of people who survived the Holocaust the account of a Hungarian Jesuit who became the witness of one of its countless episodes. Through a hole in the wooden fence surrounding a railroad station from where Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz, the Jesuit sees an open wagon packed with people: a man who asks for something (maybe water) is dragged out of the wagon and beaten up by an SS guard; at this moment, the man peeping through the hole in the fence runs away, the sequence is interrupted, and the fate of the tortured man remains for the observer forever unknown.

The psychoanalyst13 accompanying the recording of this testimony immediately discovers the point of greatest denial when he asks the Jesuit why either then, or later, he said nothing to anyone about this incident – why he denied his experience as a witness. Since it was not the incident itself, according to the therapist, that provoked denial, but the situation of being an observer: the obscene circumstances of watching someone else’s humiliation through a hole in a fence, the embarrassing state of passivity, a feeling of impotence – in other words, the status of a curious gaper. The witness’s long silence, which followed this question, is preserved on the video tape. ‘Suddenly before our eyes he is wrestling with the deep memory of his own inaction, which common memory clearly disapproves of today and he is trying inwardly to explain to himself before he can explain it to us – and so far, he does not have an explanation.’14 Langer analyses the breaking down of the safe ‘staged-ness’ of that situation during the giving of testimony: the fence and a suitable distance from the observed event cease to protect the observer; the event eliminates the distance, consumes the observer, relocates him from his hiding place to the very centre of the scene, and brings to a crisis the notions of man that had hitherto guided his life. Such were the irremovable results of being in the position of an observer of the Holocaust and accepting the rule of theatricality (according to which a witness ceases to be a witness and becomes a spectator, and therefore doesn’t have to take action). Langer sees only two resolutions to this crisis: either hitherto existing visions of humanity succumb to total breakdown, or they are consolidated in the form of delusions, sustained despite the reality of lived experience. He does not explain, however, what inclined the Hungarian Jesuit to bear witness. We do not find out either why Langer chose precisely this testimony (the only testimony of an observer analysed by him) in order to discuss the position of the bystanders. One can only surmise that the fact that it involved a priest, a representative of the Catholic Church, was not without significance to him.

As Elaine Scarry asserts in her book The Body in Pain, it is not only the person upon whom pain is inflicted who loses the linguistic tools to describe their situation: the same is true of the witness to the torture – the stable frames for perceiving the world succumb to weakening and frustration. Pain, before totally destroying the powers of language, colonizes them. The lack of appropriate descriptive tools makes a witness of someone else’s suffering prepared to accept the descriptions provided by authorities or ‘priests of an angry God’.15

Thanks to someone else’s pain, authority justifies its ideologies, filling them with the reality of someone else’s experience, while the ‘priests of an angry God’ represent a pain event that the human mind is incapable of assimilating as a manifestation of the ‘higher morality’ of the divine order.

3.

When we apply Hilberg’s triad of participants in the Holocaust to Polish witnesses, a vision of Polish post-war culture as one of ‘witnesses’, ‘observers’ or simply ‘gapers’ becomes immediately apparent. Czesław Miłosz’s poem ‘Campo di Fiori’ remains paradigmatic in this respect, written under the direct impression of Polish indifference to the final liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. But we find this same motif of Polish witnesses to the extermination of the Jews in the stories of Tadeusz Borowski, in Zofia Nałkowska’s novella ‘Przy torze kolejowym’ (‘By the Railway Track’) from her Medallions, in Jerzy Andrzejewski’s Wielki Tydzień (Holy Week), Seweryna Szmaglewska’s Dymy nad Birkenau (Smoke over Birkenau), Stefan Otwinowski’s play Wielkanoc (Easter), Aleksander Ford’s film Ulica Graniczna (Border Street), in the volume of journalistic articles Martwa fala (Dead Wave) edited by Andrzejewski, and also subtly resonant in Tadeusz Różewicz’s first book of poetry – to mention only works written still during wartime or just after the war, under the direct impact of events, or immediately following them. Literature, film and journalism were governed by the ubiquitous procedure of eyewi...