![]()

Imperative 1

Plan Your Time Wisely

Aside from their lesson plans, many teachers have a vague sense of what they want to accomplish on any given day; consequently, when the school day starts, they are simply washed through the hallways and spit out at the end of the last period. Certainly, they can have a meaningful impact on students; certainly, they can be productive educators. But most of them are not using time as effectively as they might. I want to change the way teachers relate to time. I want them to think about time the way conductors think about sound. Each day can be a symphony rather than a muddled mess that ends with a dry throat, an exhausted thump in any chair that will have you, and a vague sense of unease about things left undone and problems left unsolved. The idea is to make things happen, and not just allow things to happen to you.

Successful educators are mindful and intentional. They constantly ask themselves why they are presenting certain lessons, how they are dealing (or not dealing) with certain students, and what they might be doing next week or the week after to create continuity in their classes. Planning one’s outside-the-classroom time can eliminate undue anxiety and, therefore, help sharpen teachers’ minds when they enter their classrooms. I tell teachers that anytime they have their plan book open, they are being productive and improving their effectiveness. Personally, I devote some time each week to sitting in a quiet place and reviewing my commitments for the week, my deadlines, and my expected outcomes.

I encourage you to view time as something that you generate, not something that preys on you. And your new relationship with time begins with your calendar.

YOUR CALENDAR

Spending time thinking about calendars might be the last thing in the world you’d expect passionate teachers would do. Rather, you might expect that they would commit their time to addressing curriculum, teaching strategies, and kids, right? Of course. But passionate commitment is best supported by clear systems for managing the daily influx of appointments and information that crowd our minds and lives. Without a strong, functional way to keep track of actions, events, appointments, and deadlines, you will be scattered—too scattered to give your full self to the task of education. Just as your body’s functionality, its strength and balance, radiates from your core, your calendar must be strong if you hope to function with agility, quickness, precision, and some semblance of control in a school community.

We all keep calendars, but most of us can tighten up our calendaring skills. To that end, a good practice is to acknowledge that the calendar should be a sacred space for responsibilities that absolutely must get done and are absolutely tied to specific dates and times (Allen, 2001, pp. 39, 41). Although the point might seem like common sense, teachers need to be reminded (or trained) to have one place and one place only where they write down their appointments. Too many teachers use messy sticky notes or scraps of paper to keep track of important commitments.

When teachers mismanage their calendars, they become forgetful (or only remember the big assembly, for instance, when they see someone else going to it). They miss or are tardy to meetings; they are unprepared for classes or other commitments; they fail to return phone calls or e-mails in a timely fashion; they miss deadlines. The effects of a mismanaged calendar undermine the foundation of a school thereby eroding positive thoughts and feelings about the school. Every school employee is the caretaker of the school’s mission and meaning. Botched appointments unnerve those who are prepared, those who are expecting input or a response from you, and all those who rely on your professionalism. On the other hand, if you establish a dynamic calendar, as I outline below, then you will have a strong core, and your commitment to the task of education will be supported.

Choosing a Calendar

To establish a dynamic calendar you must first choose a calendar, one calendar that will hold all your appointments. There are many types of calendars, including large, desk calendars, pocket calendars, notebook-style calendars, and electronic calendars on your computer or handheld device. Choose a calendar that you understand, one that is portable, and one that can be updated or modified quickly and efficiently. Also, choose a calendar that has relatively short time demarcations.

YOUR DYNAMIC CALENDAR

Calendar choice aside, what I’m interested in here is spurring you to think more actively about your calendar. Once you get the hang of listing all your commitments in one place at the precise time you need to do them (as recommended by Allen, 2001), you are ready to start using your calendar in a more dynamic way—to meet the needs of your community and your own, personal educational mission.

Technophobes take heart. Using your calendar in a more dynamic way does not require you to synch a handheld device with a computer, upload data to a web-based program, or transfer deadlines from one iCalendar to another. While these options can be useful to someone who is familiar with the technologies, dynamic calendaring is more along the lines of a skill set that you can use and transfer to any type of calendar. You must decide what works for your situation. If the latest technological gadgets work for you, charge them and get ready to use them. If not, sharpen your pencils. Either way, your first task is to gather and list your responsibilities so they are set clearly before you each day.

Responsibilities—Planning to Do What You Must Do

If your school has a good master calendar, this task should take about an hour, and it will save you many hours of disruption. If your school does not have a good master calendar, then work with what you have and take the time to supplement your calendar with what you can. The time spent at the front end will pay off immeasurably.

To build your own calendar, one that will ensure certainty, first you need to find your school’s master calendar or any calendar on which your responsibilities appear, and make a copy of it. Save the original in a file. Read through the extra copy for anything you absolutely must do, and circle those items. You are looking for things like grading deadlines, parent conference days, inservice, any meetings for which your presence is required, and special schedules. Circle these responsibilities. Then, as you read through the master calendar a second time and copy the circled items into your personal calendar system, put an X through each circle. Make sure that you account for start times and end times. You should not simply list items in your calendar; block out the time required. Next, read through the calendar a third time, looking only at the items that are not crossed out. Finally, you are ready to add your class schedule to your calendar. Again, walk through each week, adding both the classes and their block of time.

It pays to be thorough in this task. Once you have completed it, you will derive a sense of confidence from the fact that you know where you must be and when you must be there. Also, and perhaps more important, you have identified all the blank spaces in your calendar. Blank calendar space and how you use it is the true test of a complete teacher, one who will make contributions both inside and outside the classroom.

Priorities—Planning to Do What You Value

The two educators I remember best from high school are Tom Fox, my basketball coach, and Mary Fitzgibbons, my English teacher. Aside from some memories from the court and the classroom, what I remember best about these two are things that happened outside their usual domains of influence. Coach Fox used to show up at my other sporting events; for example, I remember, clear as day, an important track meet. Coach Fox showed up for my event, the two-mile run, perhaps the most boring and longest event at a track meet, and talked me through each lap each time I passed him in the stands. Mrs. Fitzgibbons, too, went above and beyond the call of duty by helping me arrange a writing portfolio for a creative writing conference. This had nothing to do with grammar or critical writing or the other things that went on in her classroom.

When I think about these educators, I realize that these extra, unpaid activities reflected completely their values as educators. Coach Fox believed in student athletes; he believed in supporting them in all their athletic endeavors; he believed in supporting other coaches and teams as well, serving as a fine model for collegiality. And Mrs. Fitzgibbons believed in creativity and poetry even though she had to spend most of her time in the classroom teaching students about the fundamentals of sentence construction or how to understand the surface meaning of Shakespeare’s sonnets. The “extra” things these adults did for me to support my growth still stick with me 15 years later. Coach Fox and Mrs. Fitzgibbons transcended the data about “what works” and the trends in educational pedagogy by simply following their own educational passions and understanding how to articulate and live their educational missions.

Therefore, I offer a challenge: Once you have filled in your responsibilities, your “must dos,” look at the white space as if you are an artist looking at a blank canvas. This is where you can sketch your personal vision of education, of what matters to you in school communities.

William James said that “our beliefs and our attention are the same fact” (Richardson, 2006, pp. xxiii–xiv). Do you want to support the arts in your school? Contact your school’s art teachers, band leaders, or drama coaches. Ask them to see the schedule of student events, and put a few of them on your calendar. Do you want to tutor students who perpetually underachieve? Talk to the person in your school responsible for collecting data such as student grades and PSAT scores. Identify the students who really need help, then carve out the time for them. Do you want to write an educational article for a journal? Lead a community service initiative? Help students with study skills? Plan for these endeavors, in writing, on your calendar.

If you are having trouble identifying your educational mission and values, you owe it to yourself, your school, and your students to take a few minutes to think about your personal motivation for working in schools.

Personal Alignment

When I first started writing, over a decade ago, a fortuitous experience with Vin Scelsa’s radio program, Idiot’s Delight, led me to a copy of Rainer Marie Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. I remember being deeply moved by the opening letter wherein Rilke challenges his young apprentice to consider the root causes of his vocation. He poses a difficult question: Must you write?

The answer, I think, is less important than the asking. As in most of Rilke’s work, he is not simply trying to provoke a simple yes or no. He wants his apprentice to locate and tap a hidden source of energy, one that emerges from inside the young writer.

So I ask you, must you teach? What draws you to this curious occupation that promises neither fame nor fortune? What draws you to this work that cuts into nights and weekends, that never feels finished or final?

Some of the root causes for why people teach I have heard about over the years include a love of kids, subject, learning, variety, people, and human nature; an aversion to corporations; and a belief that we can change the world one young person at a time.

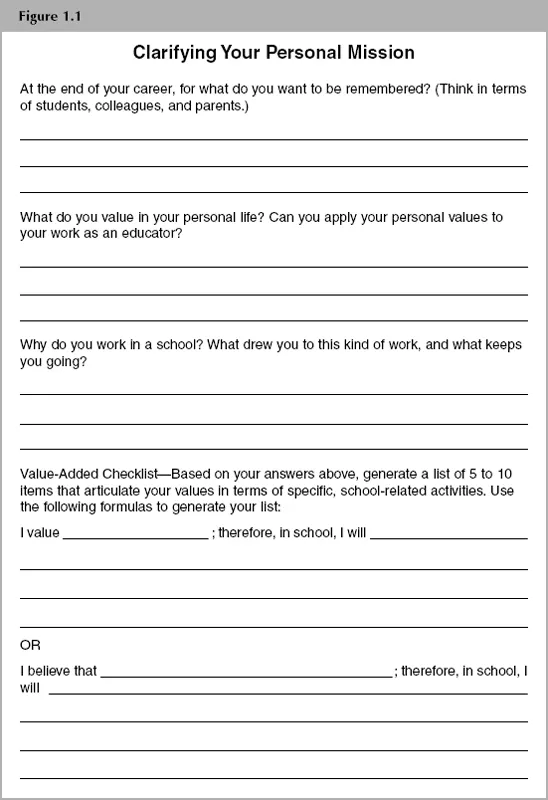

Imagine a school where people were driven by such causes instead of the usual drivers (i.e., speed, parents, test scores, administration). Getting back to Rilke, then, I would ask, how can we move from these internal motives, these secret springs of energy, to focused, efficient, sustainable systems in our day-to-day teaching life? How can we realign our daily habits and practices with our innermost convictions and beliefs about education? The questions in Figure 1.1 can help.

Although this kind of activity may seem useless to some of the more practical-minded or seasoned teachers, I contend that this process is one of the most practical forms of thinking in which a teacher, or any busy professional, can engage. We build up so much professional flab that it’s hard to see the teachers underneath sometimes. The process I’m recommending helps you to be clear (first with yourself, then with others) about how to spend your discretionary time (the time not explicitly concerned with your direct responsibilities). For example:

• If you have determined that you value and want to model a “greener” approach to school life, you can focus on finding ways to send most documents via e-mail or to post them on a website, and encourage this practice in others.

• If you have determined that you value one-on-one interactions with students, you can block out some time after school to meet with students. You can write this into your curriculum plan (assigning times when each student must meet with you), and your calendar will slowly conform to your aspirations. Ideally, if this kind of interaction is gratifying to you, you will also start to feel even better about the work you do.

• If you value the idea of being a teacher and a coach, perhaps you can find a way to do even more coaching.

If you know what you value and you are clear about it, you can slice right through the fog and noise of a school day and begin to build the kind of school life that will tap into your particular strengths and your most personal source of energy. This is how to find your voice as an educator.

Activating Priorities

An interesting way to think about your priorities, once you have isolated them, is to imagine yourself as the leader in a new, small business venture within the larger “corporation” of your school. Guy Kawasaki (2004), who directs a venture capital firm and helped develop the Macintosh computer, refers to this in a corporate environment as internal entrepreneuring. Although meant for corporate-type employees who aspire to create innovative products and services within their companies, Kawasaki’s advice regarding internal entrepreneuring also applies to teachers who aspire to start new clubs or initiatives in their current schools. Helpful “Kawasakaisms” (pp. 19–23) to keep in mind are adapted for educators below.

• Your innovation should be aimed, first and foremost, at improving the school and the lives of students.

• If possible, build on an existing program or trend.

• Galvanize other teachers; their support will be crucial, especially if your innovation becomes a schoolwide initiative.

• Collect data and share it. Schools are dynamic places, and teachers can always use data to inform their decisions.

Forecasting/Problem Solving

Once you have established (and...