- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Brain-Compatible Science

About this book

Gain fresh insights for teaching, learning, and assessing knowledge of critical science concepts through the exploration of research-based practices for science education.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

SECTION 1

Chaos Theory

Section 1 presents six chaos theory principles and their implications for reform in science education. Chaos means order without predictability or persistent instability. The science of chaos, a significant mathematical development of the twentieth century, presents a random and unpredictable world with systems that change over time. The world evolves in cycles as energy transforms matter into self-similar patterns. Systems that look chaotic have a deeper order within. Metaphors from chaos theory, the science reform initiatives, and the brain-based learning research, including the mind/brain principles proposed by Geoffrey and Renate Caine (2006), aid teachers in reconceptualizing science education by removing teachers from their traditional paradigms and guiding them to redefine science education for a nonlinear and much more complicated future world.

1

Fractals

A Metaphor for Constructivism, Patterns, and Perspective

Why is geometry often described as cold and dry? One reason lies in its inability to describe the shape of a cloud, a mountain, a coastline, or a tree. Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not smooth, nor does lightning travel in a straight line.

Benoit Mandelbrot (1983, p. 1)

BACKGROUND: WHAT IS A FRACTAL?

Perhaps the most frequently studied and visually appealing principle of chaos theory is the spectacular, computer-generated set of fractals, first conceived by modern mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot (1983). Frustrated with the perfectly regular shapes of Euclidean geometry, Mandelbrot developed a whole new geometry more in tune with the natural world. He called the irregular shapes fractals, meaning fragmented and irregular. Trees exhibit a chaotic growth plan. Clouds change constantly. Mountains result from a combination of tectonic forces and erosion processes. Nature evolves in irregular patterns: Bird beaks, canyons, sand, and waves are intricately fashioned by the dynamic forces of growth, evolution, and erosion.

Whether viewed from afar or from a closer perspective, natural irregularities repeat on smaller and smaller scales until they are no longer discernible to the human eye. The delicate shape of a fern or a feather does not behave in straight lines and perfect curves. Viewing patterns within patterns, Mandelbrot (1983) explained:

Nature exhibits not simply a higher degree but an altogether different level of complexity. The number of distinct scales of length of natural patterns is for all practical purposes infinite. (p. 1)

Nature’s patterns are never exact.

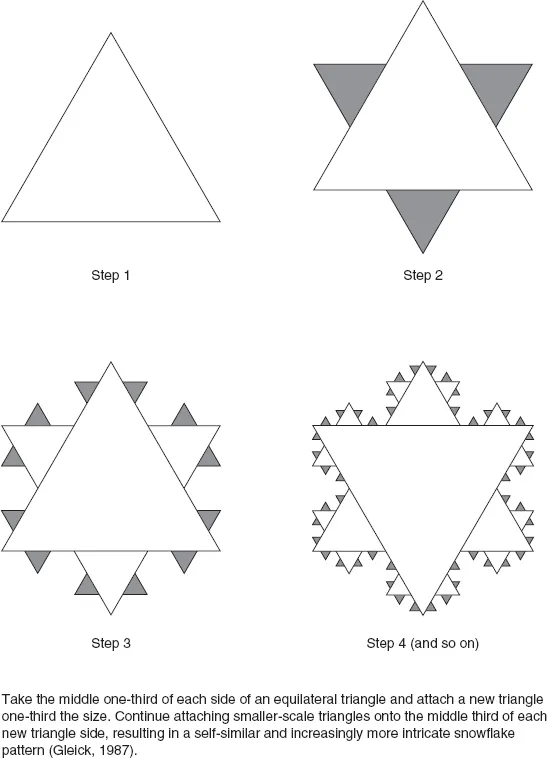

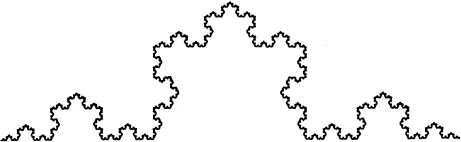

The Koch snowflake, well-known to mathematicians, is a fractal shape that was first constructed in 1904 by Helge von Koch, a Swedish mathematician. (To construct a Koch snowflake, see Figure 1.1.) When magnified and rotated, exactly four pieces of the snowflake’s edge, known as the Koch curve, yield the entire edge of the snowflake (Figure 1.2). Congruent circles may be drawn around the original triangle and each transformed view of the snowflake as it progresses from simple to complex. Although the snowflake always fits within a finite area, the perimeter of the snowflake is infinite. No piece of string could ever be long enough to fit completely around the snowflake’s edge (Devaney, 1992).

The Koch snowflake may be compared to a lake or ocean shoreline when viewed from a variety of different perspectives. Coastlines become increasingly longer as more and more detail is included in the measure. When viewed from an airplane, much of the shoreline detail is smoothed over and lost; however, when viewed from a closer perspective, more details appear, and the perimeter increases. Unless a scale is agreed on, all coastlines are infinite in length (Briggs & Peat, 1989). No wonder reference books give conflicting mileage for the same shoreline. A snail traveling around each tiny sand pebble would crawl farther than a deer would leap! Imagine following the shoreline journey of a microscopic organism.

Mandelbrot (1983) retold a story in which young children are asked how long they think the coastline of the eastern United States is. Children understand immediately that the coastline is as long as they want to make it, and that the perimeter increases as each bay and inlet is measured with increasingly smaller scales. Margaret Wheatley (1994) discussed the futility of searching for precise measures for fractal systems:

Since there can be no definite measurement, what is important in a fractal landscape is to note the quality of the system—its complexity and distinguishing shapes, and how it differs from other fractals. (p. 129)

Mandelbrot’s coastline question has no final answer.

Mandelbrot (1983) discovered a surprising paradox emerging from chaos theory and fractal geometry. Complex fractals may be generated from a simple mathematical process. In the 1980s, using computer technology, Mandelbrot first viewed the fractal set that has been described as the most beautiful image of modern mathematics (Figure 1.3). A voyage through the Mandelbrot Set reveals finer and finer scales of increasing complexity, sea-horse tails, pinecone spirals, and island molecules all resembling the whole set (Gleick, 1987). The beautiful jewel-like shapes are symbolic of the nonlinear, modern world so full of complexities and seemingly insolvable problems.

If simple leads to complex, could not the reverse be true? Margaret Wheatley and Myron Kellner-Rogers (1996) believed so when they discussed how people seek organization and order in the world, even when chaos is present at the start. “Life is attracted to order—order gained through wandering explorations into new relationships and new possibilities” (p. 6). Perhaps complex problems have simple solutions that remain hidden from view until the time is right for their simple truths to come forth.

Paradoxes such as simple to complex often appear in today’s world. Paradoxes enrich people’s thinking by providing them with more choices, allowing them to view things differently, and opening up the world for them to generate and create their own meaning. John Briggs and F. David Peat (1989) asserted that in the future fractals will undoubtedly reveal more about how chaos hides within regularity and how stability and order can arise out of turbulence and chance. New ways of doing and being may be contained within the old. Unusual and surprising patterns may emerge when least expected. If teachers were to look deeply within themselves for answers, hidden patterns, and universal themes, perhaps they could generate novel purpose and vitality to science education.

Directions for Koch Snowflake

Figure 1.1

Koch Curve

Figure 1.2

IMPLICATIONS OF FRACTALS FOR BRAIN-COMPATIBLE SCIENCE

Three implications of fractals for brain-compatible science are (1) wait for simple truths to reveal greater complexities, (2) construct new meaning from the old, and (3) search for repeating patterns and different perspectives. Parallels exist linking fractal theory to brain-compatible science. Teachers need only to look at the many natural patterns surrounding them to understand the innate ability of the human brain to make connections by constructing new meaning from the old.

Wait for Simple Truths to Reveal Greater Complexities

Wheatley and Kellner-Rogers (1996) raised significant questions about the role of structure. They wondered what people could accomplish if they stopped trying to impose structure on the world and instead found a simpler way of doing things by working with life’s natural tendency to organize. Educators might ask this question of themselves as they begin a lesson with their students. Life’s events are patterned similarly yet differently each day. Their beautiful, fractal patterns occasionally reveal themselves, often times taking people by surprise. Will people be receptive to the simple truths of life’s events when patterns emerge? Perhaps fractals can teach educators something about simplifying the educational process.

Teachers tell students to line up, get it straight, sit up straight, don’t get out of line, toe the line, stay on the mark. But where is the line? Where are the mark and the straight? Perhaps they are still back in the age of machines and clockwork precision. Teachers’ zest for lesson planning, structuring, and assessing often overshadows the sparks of creative insight that they forget to look for. In a frenzy to get things done and to prepare for tomorrow or next week, teachers rush from one thing to the next, missing out on beautiful moments of fractal simplicity. Perhaps teachers need to slow down, allowing their brains to reveal the simple truths hidden in the complex schedules and endless lists of things to do. Freed from the complexities that get in the way of life’s natural tendency to organize, teachers may find a much more creative and energetic form of complexity, one that leads to new discoveries and new understandings about the educational process.

Construct New Meaning From the Old

Geoffrey and Renate Caine, current leaders in brain and learning theory, b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Publisher’s Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Introduction: Envisioning a New Paradigm for Science Education

- Section 1 Chaos Theory

- Section 2 New Science Principles

- Section 3 Chaos Theory and New Science Principles Summary

- Glossary

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Brain-Compatible Science by Margaret Angermeyer Mangan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Teaching Methods. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.