![]()

1

BASICS

THE CAMERA—HOW IT WORKS

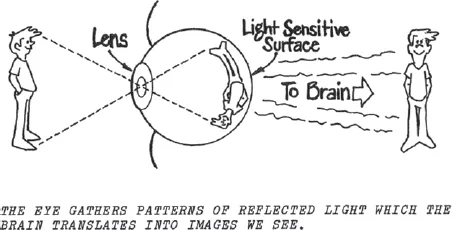

The camera is an imperfect imitation of the human eye. Like the eye, it sees by means of a lens which gathers light reflected off objects. The lens directs this light onto a surface which senses the pattern formed by the differences in brightness and color of the different parts of the scene. In the case of the eye, this surface at the back of the eye sends the pattern of light to the brain where it is translated into an image which we “see.”

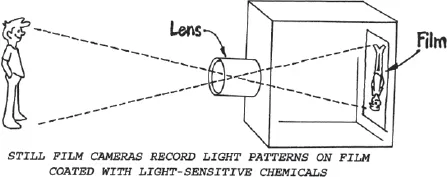

In the case of the camera, the lens directs the patterns of light onto a variety of sensitive surfaces. Still film cameras record light patterns on film coated with light-sensitive chemicals. The chemicals react differently to different amounts and colors of light, forming a record, or image, of the light pattern. After the film is processed in other chemicals, the image becomes visible.

You’ll notice that both the lens of the eye and the lens of the camera turn the light pattern upside down as it passes through. This is because they’re both convex lenses, or lenses which curve outward. Because of their physical properties, convex lenses always invert images. In the brain, and in the camera viewfinder, the images are turned right side up again.

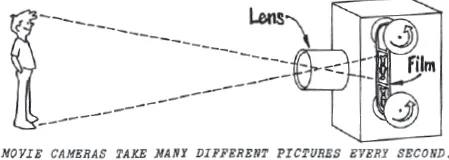

Movie cameras record images in the same way as still film cameras, except they do it more often. Eight mm movie cameras normally take eighteen different pictures, or frames, every second. Sixteen mm and 35mm movie cameras take twenty-four frames per second. When these pictures are projected on a screen at the same fast rate, they give the illusion of continuous movement. The viewer’s mind fills in the gaps between the individual frames, due to a physiological phenomenon known as persistence of vision.

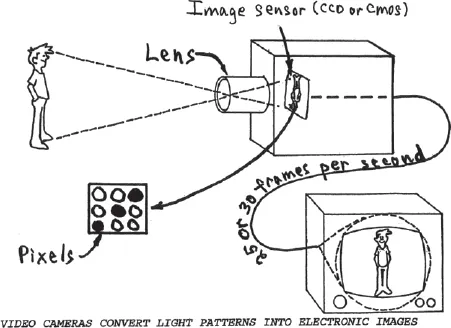

In digital cameras—both still and video—the lens focuses light patterns onto an image sensor, either a CCD (charge coupled device) or a CMOS (complementary metal oxide semiconductor). The surface of the sensor contains from thousands to millions of tiny light-sensitive areas called picture elements, or pixels, which change according to the color and intensity of the light hitting them. In video cameras, the image formed by all the pixels taken together is electronically collected off the sensor at a rate of either twenty-five or thirty complete images per second. These images can then be recorded or broadcast. (See illustration on following page.)

At the viewfinder or TV set the process is reversed to recreate the original image. Persistence of vision causes the viewer to perceive the separate pictures, or frames, as continuous movement.

EXPOSURE

Exposure is the amount of light that comes through the lens and hits the film or CCD chip. The hole in the center of the lens that the light travels through is called the aperture. If the aperture is big, it lets in lots of light. If it’s small, it lets in very little light. The size of the aperture is adjusted by the f/stop ring on the outside of the lens. An f/stop is simply a measure of how big or how little the aperture is.

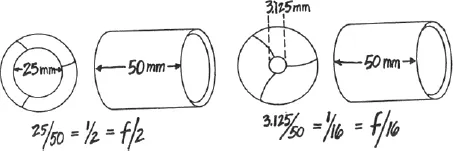

I find that the easiest way to understand f/stops is to think of them in terms of fractions, because that’s what they really are. F/2 means that the aperture is 1/2 as big across as the lens is long. F/16 means that the aperture is l/16th as big across as the lens is long.

When you look at it this way, it’s easy to understand why in a dark room, you’ll probably be shooting at f/2 to let in all the light you can. Conversely, outside in bright sunlight, where you’ve got a lot of light, you’ll probably stop down to f/11 or f/16, to let less light in.

Now that you understand that, let me point out that in most modern lenses, especially zoom lenses, what I’ve just told you isn’t absolutely true. An f/2 aperture won’t physically be exactly 1/2 the length of the lens. But optically it will be. It will let through as much light as if it were indeed 1/2 the length of the lens. And that’s the important thing.

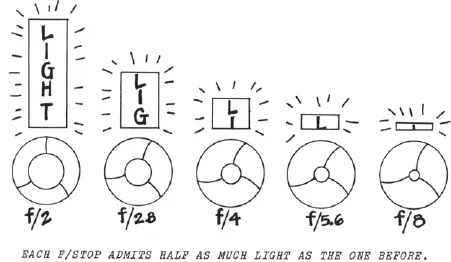

F/stops are constructed so that as you go from f/1 to f/22 and beyond, each stop admits 1/2 as much light as the one before. The progression is: f/1, f/1.4, f/2, f/2,8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, f/32, f/45, f/64, and so on. F/1.4 admits half as much light as f/1. F/4 admits half as much light as f/2.8.

Many of the newer lenses are marked in both f/stops and T/stops, or T/stops alone. T/stops are more accurately measured f/stops. F/4 on one lens may not let in exactly the same amount of light as f/4 on another lens; but T/4 is the same on every lens. It always lets in the same amount of light.

COLOR TEMPERATURE

Have you ever been out walking on a cold, dingy day and remarked to yourself how warm and cozy all the lighted windows looked? Well, that was because the light in the windows was of a warmer color than the light outside.

Yes, light comes in different colors. If you think about it, you’ll see it’s true. There’s the red glow from an open fire or a sunset; the bluish cast of a sky dark with rainclouds; and that blue-green ghoulish look you get from the fluorescents in all-night pizzerias. As a general rule, our eyes adjust so well to these different colored light sources that we hardly notice them. Not so the camera.

Color films and CCD/CMOS chips can handle only one color of light source at a time and reproduce colors accurately. They do this by means of color temperature and color filters.

Color temperature is a way to identify different colors of light sources. It’s measured in degrees Kelvin, after Britain’s Lord Kelvin, who devised the system. It’s written like this: 2500K.

The idea is, you take a perfectly black body, like a piece of coal, at absolute zero (-273°C), and start heating it up. As it gets hotter, it puts out different colors of light: first red, then blue, then bluish-white. The different colors of light are identified by the temperatures at which they occur. 2000K is the reddish light produced at 2000 degrees Kelvin. 8000K is the bluish light produced at 8000 degrees Kelvin.

As I mentioned above, color films and CCD/CMOS sensors can handle only one color of light source at a time. To take pictures under a different colored light source, color filters are used to convert the existing light to the color temperature required.

Professional video cameras have built-in filters, which you set according to the light you’ll be shooting under. A typical filter selection might include: Tungsten-Incandescent (3200K); Mixed Tungsten and Daylight/Fluorescent (4300K); Daylight (5400K); and Shade (6600K). (Fluorescent light, strictly speaking, has a discontinuous spectrum and doesn’t fit into the Kelvin system; still, a 4300K filter setting will give you adequate color reproduction.)

Once you select the correct filter on a video camera, fine tune the color by adjusting your white balance. This procedure varies from camera to camera and can be as simple as pushing a single button. It ensures that the whites in your scene reproduce as whites; the other colors then fall into place.

Color movie films are manufactured for two kinds of light: 3200K-tungsten (interior); and 5400K-daylight. If you shoot tungsten film in tungsten light, you don’t need a filter. Likewise if you shoot daylight film in daylight.

To shoot tungsten film in daylight, put a #85 filter on the front of the lens or in a filter slot on the camera. This orange filter converts 5400K bluish daylight to reddish 3200K tungsten.

To shoot daylight film inside with tungsten light, use a #80A filter. This blue filter converts reddish tungsten light to bluish daylight. For photoflood lights (3400K) use a #80B filter.

SETTING EXPOSURE ON A VIDEO CAMERA

First, select the correct filter and adjust your white balance, as discussed above.

If your camera has automatic exposure and you can’t turn it off, all you can do is avoid large light areas and large dark areas within the frame. These will throw your exposure off.

Professional video cameras have both auto and manual exposure. To manually change your exposure, look in the viewfinder and move the f/stop ring until the picture looks good. Ideally, you’ll be able to record detail in both the bright (highlight) areas and the dark (shadowed) areas. Most camera viewfinders can highlight overexposed areas with non-recording zebra stripes.

With a new or strange camera, it’s a good idea to make a test recording under various lighting conditions and play it back on a good monitor to check the calibration of your camera’s viewfinder. Sometimes you’ll have to go a little darker or a little lighter in the viewfinder to get the best color on playback.

The main problem with video cameras is large areas of white, particularly those caused by strong backlight-light shining toward the camera from behind the subject. If you include too much pure, bright white in your frame, all the other colors go dark. Sometimes the white will “bleed” over into the other colors. White problems are seen clearly in your vie...