eBook - ePub

The Photography Exercise Book

Training Your Eye to Shoot Like a Pro (250+ color photographs make it come to life)

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Photography Exercise Book

Training Your Eye to Shoot Like a Pro (250+ color photographs make it come to life)

About this book

• Use simple exercises to learn to see and shoot like a pro rather than painfully following strict rules.

• This book covers a wide variety of genres (street documentary, photojournalism, nature, landscape, sports, and still-life photography).

• The Author has helped 1, 000's of photographers to date. In this revised edition, he includes over 250 beautiful color photographs to make his exercises come to life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Photography Exercise Book by Bert Krages in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Photography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Foundations for Learning to See

The fundamental perceptual skills associated with photography are seeing, composition, and evaluation. Some photographers seem to possess a natural gift for these skills, but for others they can be baffling. There are many reasons why the ability to see a scene as it objectively appears varies among people. However, the most notable is that the eye and brain work together much differently than a lens and camera do. Likewise, although most people can recognize good composition when they see it, some photographers find it difficult to achieve a well-composed image without resorting to the rote application of the guidelines known as the rules of composition. In a similar vein, some photographers recognize that their images are somehow lacking, but find it difficult to discern why. The good news is that these skills are not especially mysterious and can be improved by understanding and developing them.

In some ways, photography is similar to physical fitness—if you really want to improve, you need to work at it. Another aspect these two things have in common is that success is far more dependent on effort and discipline than on equipment. The mere act of engaging in activity will help anyone get better, but working with a consistent plan is the best approach. Improvement will come by being deliberate in what you do and working especially hard at the things that are causing you to fall short.

A good part of photographing is simply getting out with a camera and exploring places and ideas. The more you work at being observant and finding opportunities, the more you will improve.

Recognize that nothing will give you a better feel for photographic skills than actually taking photographs. Doing this will make it clear what is not working and where your weaknesses are. Once you have identified an area in which you want to improve, you can concentrate on improving that specific area. Furthermore, it is easier to push yourself to make your images even better when you recognize what “even better” looks like. Good photographers are good because they have mastered the fundamentals and put themselves in situations where they can make good images. However, don’t expect that every photograph you take has to be a work of art, or that every session has to result in a good image. You can practice taking photographs in almost any setting, and even taking mundane photographs can help you improve your skills so that you are better able to take advantage of more meaningful opportunities.

Expect to spend a lot of time taking photographs before you can consistently produce images that meet your goals and expectations. Developing strong perceptual skills requires putting mental effort into making images. When you are trying to master a particular skill, just going through the motions will not be very effective, nor will doing something a couple of times and then moving on. You need to concentrate on the task at hand and try to work for some form of sustained achievement.

The Importance of Seeing

Seeing is the ability to observe what is in a scene and to recognize the potential ways a scene can be depicted in a photograph. It is the most fundamental of the basic skills because it not only determines which visual elements will appear in an image, but it also influences the decision to make the image. Some people believe that seeing is a mysterious gift, the so-called artist’s eye. The reality is that almost anyone can learn the skill of seeing, particularly when they understand how the brain receives and processes visual information. For many people, the difficulty in seeing arises from the left hemisphere of the brain interpreting the information from the eyes by abstracting and symbolizing. This enables a person to efficiently register the most important objects in their line of vision and is a way of controlling information overload. However, this process also causes people to perceive objects differently than how they actually appear. For example, most people believe that telephone poles are always vertical even when they are often slightly tilted. In the same way, because people understand that the rails of railroad tracks are parallel, they do not notice that the rails appear to converge as they recede into the distance. When viewed in a left-brain frame of mind, a scene will often register differently from its actual appearance. For example, parallel lines will seem parallel, vertical objects seem vertical, and foregrounds and backgrounds are free of distracting content. However, cameras lack the ability to do this kind of mental filtering, and thus only record the scene as it appears in front of them. It is thus the difference between a filtered perception and unfiltered reality that causes many photographs to fall short of what they intended to record.

Seeing is relatively easy to improve but ironically presents a major challenge to many photographers. The reason that seeing is easy to improve is that it generally only requires the photographer to shift into the cognitive form of visualization that is primarily controlled by the right hemisphere of the brain. Conversely, the reason that seeing can be a challenge is that it entails bringing together diverse elements such as shapes, emotions, and motions into a unitary, static whole. However, pursuing this challenge is a large part of what makes photography interesting.

Photographers can learn a lot about seeing and composition from artists who work in other two-dimensional media. One of first areas to examine is the learning process itself. Visual artists, when learning to draw and paint, immediately recognize the need to improve their perceptual abilities because they work in media in which pigments are placed by hand onto a blank surface. Unless they learn to perceive what their subjects actually look like, it is nearly impossible to depict objects realistically. Photographers are less likely to recognize problems with perception because cameras automatically address visual issues such as contour, perspective, and value. By subsuming many of the mental tasks associated with rendering scenes, the camera can mask areas where improvement of visual skills is needed.

The camera’s ability to record visual features without human cognition of the scene has affected how photographic composition has been taught. Since the end of the nineteenth century, when photography became feasible for the masses, photographic composition has generally been taught as the application of design principles from the graphic arts to two-dimensional images. These concepts range from the very basic such as the “rule of thirds” and “s-curves” to the more esoteric such as “notan,” which is a term from Japanese art that pertains to the balance of dark and light masses. Traditional art skills such as discerning edges, determining proportions, and judging perspective have not been taught to photographers because they are largely unnecessary to the process of fixing a photographic image. However, it is through learning these skills that most artists have learned how to see.

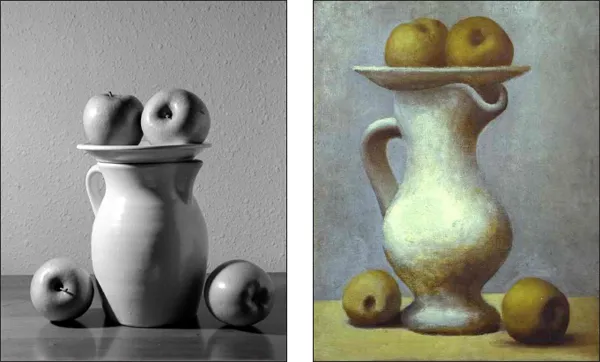

A good way to appreciate the difference between photography and other fine arts such as painting is try to do something that has been previously done in a different medium. Although the camera enables the photographer to capture details and render perspective automatically, painting provides much more control over what to put in and what to leave out. Copying the works of master artists is a time-honored learning technique in the traditional fine arts. As can be seen in this comparison with Pablo Picasso’s Still Life with Pitcher and Apples (1919), the way content is rendered by various media very much affects what is communicated.

A major difference between the graphic arts and fine arts is that graphic artists are taught how to express concepts visually. Graphic design principles are particularly useful for communicating abstract concepts such as calm, unease, and velocity. These principles can be and often are applied to photographs. They are likewise used in abstract fine art. However, achieving the sense of realism associated with traditional forms of fine art requires cognitive skills that differ from those required for graphic design. The “something more” aspect is the ability to perceive the elements in a scene and depict them on a two-dimensional surface.

The problem that many people have with perception has been explained by research in the field of psychobiology. This research has shown that the model of the eye as a “camera” that sends images to the brain is largely false. Instead, the eye and brain work together in a way that provides the brain with the information it needs to handle the tasks before it. Much of the time, the eye-brain combination disregards most of the visual information encompassed by the lens of the eye. For example, when you are reading a book, you probably are not conscious of the gutter where the pages connect, the margins surrounding the text, your hands, or the table on which the book is resting. Reading is an analytical skill in which the brain assembles the visual elements produced by letters and abstracts them into conscious thought. What you perceive when reading are the thoughts abstracted from the words. The extraneous elements are suppressed from conscious thought. On the other hand, if you are looking at what features distinguish one typeface from another, you are unlikely to be conscious of the thoughts expressed by words formed by the letters of the typeface. Instead, you become cognizant of features such as the serifs, weight, and descenders associated with the typeface.

Most people who have not studied arts such as drawing and painting believe the eyes are located higher than they actually are. If you look at this image, you can see that eyes are almost always located at the midlevel of the skull.

Most of the time, limiting conscious perception to the elements that are relevant to the task at hand is a good thing. Otherwise, you would suffer from information overload. However, the brain’s propensity to process information analytically can present a problem to photographers. Analytical tasks such as reading and mathematics rely extensively on symbols and the discretionary elimination of sensory clutter. Since this kind of thinking actually suppresses visual perception, it can present a barrier to acquiring proficiency in the visual arts. People who have become conditioned to rely on symbols in discerning their environment are prone to disregard details and misconstrue spatial relationships. For example, most people when asked to sketch a human face will place the eyes at the upper third of the skull, although they are usually located at the midlevel. If you want to test your ability to disregard the brain’s tendency to rely on symbols instead of reality, try sketching a face working from a real person or a photograph and see how well you do.

The inability to shift readily into a cognitive perception mode can present problems during photography. One problem is that perception is needed to ascertain visual opportunities for taking photographs. For example, photographers who want to photograph insects will not do very well if they are unable to find any insects to photograph. Ironically, insects are extremely abundant, although many people can go days without noticing any. For some people, the problem is that they do not know where to look for insects. But for many, the problem is not knowing how to look for insects. Unless the brain is cognitively attuned to insects, it will often fail to consciously register information that insects are within the field of vision.

Another problem many people have with perception is the failure to notice important detail. In this aspect, photography is more difficult than visual arts such as drawing and painting because the camera records the objects in front of the lens irrespective of whether or not the photographer sees them. For example, if an artist who is drawing a flower fails to notice the lint between the petals and on the stem, it will not show up in the drawing. Photographers do not have the luxury of unconscious omission. This is the reason why some photographers, when taking photographs, fail to notice objects in backgrounds and foregrounds that detract from their images.

Although Western education traditionally has emphasized analytical skills such as reading, writing, and arithmetic, it is fairly easy to develop one’s perceptual skills. The landmark work in this area is the popular art education book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Professor Betty Edwards. Her book lays out the neuroscience of how the left hemisphere of the brain is responsible for analytic thought and processing symbols, whereas the right hemisphere is responsible for spatial cognition and intuitive functioning. By integrating the principles of neuroscience into art education, she found that almost anyone could be taught to make realistic drawings through a series of exercises that are designed to cause a shift from the left hemisphere mode of thinking to the right hemisphere. These exercises progress through the five component skills needed to draw realistically:

• The perception of edges

• The perception of spaces

• The perception of relationships

• The perception of lights and shadows

• The perception of the whole

By working through the exercises, students necessarily acquire the ability to perceive a scene in the actual manner it appears. In other words, they learn the skill of seeing.

Photographers also need to acquire these skills, although the reasons differ somewhat from those associated with drawing. In photography, the camera handles the delineation of edges without inviting mental effort on the part of the photographer. Nonetheless, skill at perceiving edges is important to photography because it is needed to recognize details that will augment or detract from the image and to discern how shapes will relate to each other after the camera makes the translation from three dimensions to two. The perception of edges is also one of the skills in which the abstracting and symbol-imposing abilities of the left hemisphere of the brain are most apt to interfere. When this happens with drawing, it typically results in a work that markedly departs from what the artist was trying to achieve. However, artists are free to erase the incorrectly drawn area or observe the subject more carefully and redraw. Unfortunately, the intrusion of the left brain into the process of photography is more difficult to detect and repair.

The ability to perceive spaces is of equal importance in drawing and photography. Many photographers are not even aware that there are two kinds of spaces to perceive. Positive space is the space taken up by a tangible object, and negative space is the space that surrounds it. Proficient artists are constantly making use of negative space because depicting the negative spaces often results in more accurate depictions of objects and their relationships to each other. Developing the ability to perceive negative spaces in photography is just as important, even though the camera automatically takes care of the accuracy issue. The reason is that the size, shape, and distribution of negative spaces frequently dominate compositions. When adequate attention is given to the negative spaces, the basic composition will usually take care of itself. Negative spaces can be used to accomplish many things such as evaluating the composition of moving objects, heightening the awareness of extraneous objects in the foreground and background, and discerning the existence of mergers where a background object appears in the image to be a part of a superimposed object.

The perception of relationships is as critical in photography as in drawing, possibly even more so. When drawing, artists invariably move their heads around a little bit, which results in minor variations to the viewpoint and perspective. When working from real subjects this can cau...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Foundations for Learning to See

- Chapter 2 Proficiency with Your Camera

- Chapter 3 Preparing to Do the Exercises

- Chapter 4 Seeing Light

- Chapter 5 Approaches to Composition

- Chapter 6 Seeing the World around You

- Chapter 7 Thinking Like an Artist

- Index

- About the Author