- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

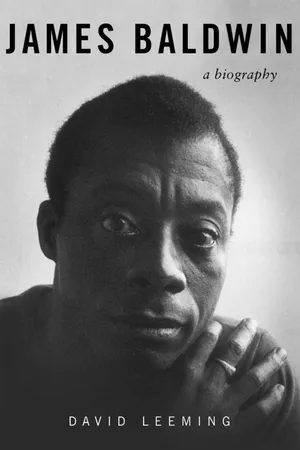

James Baldwin was one of the great writers of the last century. In works that have become part of the American canon—Go Tell It on a Mountain, Giovanni’s Room, Another Country, The Fire Next Time, and The Evidence of Things Not Seen—he explored issues of race and racism in America, class distinction, and sexual difference. A gay, African American writer who was born in Harlem, he found the freedom to express himself living in exile in Paris. When he returned to America to cover the Civil Rights movement, he became an activist and controversial spokesman for the movement, writing books that became bestsellers and made him a celebrity, landing him on the cover of Time.

In this biography, which Library Journal called “indispensable,” David Leeming creates an intimate portrait of a complex, troubled, driven, and brilliant man. He plumbs every aspect of Baldwin’s life: his relationships with the unknown and the famous, including painter Beauford Delaney, Richard Wright, Lorraine Hansberry, Marlon Brando, Harry Belafonte, Lena Horne, and childhood friend Richard Avedon; his expatriate years in France and Turkey; his gift for compassion and love; the public pressures that overwhelmed his quest for happiness, and his passionate battle for black identity, racial justice, and to “end the racial nightmare and achieve our country.”

Skyhorse Publishing, along with our Arcade, Good Books, Sports Publishing, and Yucca imprints, is proud to publish a broad range of biographies, autobiographies, and memoirs. Our list includes biographies on well-known historical figures like Benjamin Franklin, Nelson Mandela, and Alexander Graham Bell, as well as villains from history, such as Heinrich Himmler, John Wayne Gacy, and O. J. Simpson. We have also published survivor stories of World War II, memoirs about overcoming adversity, first-hand tales of adventure, and much more. While not every title we publish becomes a New York Times bestseller or a national bestseller, we are committed to books on subjects that are sometimes overlooked and to authors whose work might not otherwise find a home.

In this biography, which Library Journal called “indispensable,” David Leeming creates an intimate portrait of a complex, troubled, driven, and brilliant man. He plumbs every aspect of Baldwin’s life: his relationships with the unknown and the famous, including painter Beauford Delaney, Richard Wright, Lorraine Hansberry, Marlon Brando, Harry Belafonte, Lena Horne, and childhood friend Richard Avedon; his expatriate years in France and Turkey; his gift for compassion and love; the public pressures that overwhelmed his quest for happiness, and his passionate battle for black identity, racial justice, and to “end the racial nightmare and achieve our country.”

Skyhorse Publishing, along with our Arcade, Good Books, Sports Publishing, and Yucca imprints, is proud to publish a broad range of biographies, autobiographies, and memoirs. Our list includes biographies on well-known historical figures like Benjamin Franklin, Nelson Mandela, and Alexander Graham Bell, as well as villains from history, such as Heinrich Himmler, John Wayne Gacy, and O. J. Simpson. We have also published survivor stories of World War II, memoirs about overcoming adversity, first-hand tales of adventure, and much more. While not every title we publish becomes a New York Times bestseller or a national bestseller, we are committed to books on subjects that are sometimes overlooked and to authors whose work might not otherwise find a home.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Harlem Life

Go tell it on the mountain, over the hills and everywhere. Go tell it on the mountain that Jesus Christ is born.

—old song

Illegitimacy and an almost obsessive preoccupation with his stepfather were constant themes in the life and works of James Baldwin. The circumstance of his birth, to Berdis Jones on August 2, 1924, in New York City’s Harlem Hospital, was later to symbolize for him the illegitimacy attached to an entire race within the American nation. If Baldwin ever knew who his real father was, he kept the knowledge to himself. He preferred to use the fact of his illegitimacy, as he did his minority status and his homosexuality, as supporting material for a mythical or representative persona indicated in such titles as Nobody Knows My Name, No Name in the Street, or “Stranger in the Village.”

It is true that much of Baldwin’s early life was concerned with a search for a father, but not for a biological father—he nearly always referred to his stepfather as his “father” and seemed satisfied to think of him as such. His search was, rather, for what an ideal father might have been for him—a source of self-esteem who would have supported and guided him in his quest to become a writer and a “preacher.” And by extension, his search was a symbolic one for the birthright denied him and all “colored,” “negro,” or “black” people, so defined by others who insist on thinking of themselves as “white.”

That Baldwin would approach his life’s story metaphorically and symbolically was evident even before he was to speak of his illegitimacy. The first important nonfictional autobiographical statement is the 1955 essay “Notes of a Native Son,” in which, as Horace Porter has recognized, Baldwin strikes a “universal note, connecting his life and family to all mankind.” In the autobiographical notes to the collection of which “Notes of a Native Son” was the title essay, Baldwin spoke of the importance of being forced early in his life to recognize that he was “a kind of bastard of the West.” Baldwin was not a conceited man, but he was to look back upon his birth and his childhood as part of a prophetic mission. He saw himself as, like it or not, born to “save” others through the word.

As a child he had a favorite hill in Central Park, where he would escape whenever possible, look out over the great city, and, like his fictional character, John, in Go Tell It on the Mountain, dream of a messianic future:

He felt like a long-awaited conqueror at whose feet flowers would be strewn, and before whom multitudes cried, Hosanna! He would be, of all, the mightiest, the most beloved, the Lord’s anointed; and he would live in this shining city which his ancestors had seen with longing from far away.

The writer/spokesman-to-be was born, like so many mythic heroes, in an overlooked place where pain and deprivation were common, a place that remains today an appropriate metaphor for the spiritual meanness of the larger surrounding community, which both fears and ignores it. Rising out of Harlem, James Baldwin used the mystery of his parentage and his humble birth, and the ineffectualness of his stepfather, as starting points for a lifelong witnessing of the moral failure of the American nation—and of Western civilization in general—and the power of love to revive it.

James’s stepfather, “the great good friend of the Great God Almighty,” was the son of a slave called Barbara who spent the last years of her life, bedridden, in the Baldwin household in Harlem and who filled the young James with awe. One of his first memories was of the old woman giving him a present of a decorated metal candy box that was full of needles and thread. Inevitably, his grandmother was a link to the whispered horrors of what to a child must have seemed like the ancient past. And as the mother of fourteen, some “black” and some—it was said—“white,” she would just as inevitably become for James Baldwin, the writer and prophet, the prototype of that ancient forced motherhood that makes black and white Americans “brothers” and “sisters” whether they like it or not.

David Baldwin was a preacher and a laborer who came to the North from New Orleans in the early 1920s and who provided for his family inadequately but as well as he could through the years of the Great Depression. Not only did he take the place for Jimmy of the father he had never known, he too became for him a symbol. He was the archetypal black father, one generation removed from slavery, prevented by the ever-present shadow and the frequently present effects of racial discrimination from providing his family with what they needed most—their birthright, their identity as individuals rather than as members of a class or a race. “I’m black only as long as you think you’re white,” his stepson was to tell many audiences in later years. The Reverend David Baldwin was living proof of this fact. His bitter subservience to bill collectors, landlords, and other whites led the young James to disrespect him. In “Notes of a Native Son” Baldwin recalls his stepfather’s agreeing reluctantly to a teacher’s taking him to a play, not daring to refuse permission, the boy believed, only because the teacher was white. This was an outing Jimmy wanted very much, but he wanted much more a father whose word and opinions—however wrong—could be heard and respected.

Today’s statistics tell us that fathers in David Baldwin’s situation often leave home. But Jimmy’s stepfather did not leave home—he went mad. But he did so in stages, beginning in the South before he migrated to New York. If the “white devil” would not recognize him as a man, perhaps God would. He became a preacher, stressing, in the tradition of the pentecostal black church, the hope for a better life after the “crossing over,” and calling down the wrath of God on the sinners of the white Sodom and Gomorrah. In the pulpit his bitterness and despair could become righteous anger and power. The subservient wage earner could become the Old Testament prophet preaching the hard and narrow path to self-identity and self-esteem that the economics of real life made impossible: “Choose you this day whom you will serve; whether the gods which your fathers served that were on the other side of the flood, or the gods of the Amorites, in whose land ye dwell: but as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.”

To the people of his house the father’s prophecy took the form of an arbitrary and puritanical discipline and a depressing air of bitter frustration which did nothing to alleviate the pain of poverty and oppression. Instead of the loving father for whom the young James so longed—the father he was still trying to create in his very last novel—the Baldwin family suffered the presence of a black parody of the white Great God Almighty so essential to the tradition of the Calvinist American Dream they were not allowed to share.

As a very young child, before the arrival of the eight brothers and sisters, Jimmy had experienced a sense that his stepfather loved him. One of his earliest memories was of being carried by his mother and looking over her shoulder at his stepfather, who smiled at him. And he remembered sensing “my daddy’s pride” in him in those days. But as things became more difficult for the Baldwins, the minister’s paranoia developed, and young Jimmy often took the brunt of it. His stepfather had him circumcised at about the age of five—perhaps to make him more “Christ-like,” somehow less “primitive” and less marked by the “sin” of his illegitimacy. This incident is ambiguously described by Baldwin as “a terrifying event which I scarcely remember at all.” He did recall very clearly being beaten for losing a dime he had been given to buy kerosene for the stove—the last dime in the house. It seemed he could do nothing right.

An enduring and ever-present memory was of his stepfather making fun of his eyes and calling him the ugliest child he had ever seen. To the end of his life Baldwin told of an incident related to that memory, an incident that he felt had affected the course of his life. In the streets one day when he was perhaps five or six, he was astounded by the sight of an old drunken woman with huge eyes and lips. He rushed upstairs and called his mother to the window. “You see? You see?” he said. “She’s uglier than you, Mama! She’s uglier than me!” His mother had the same eyes and mouth that he did, so he assumed she must be “ugly,” too, and that she would therefore be interested in what he had seen. Later Baldwin would suggest, with respect to his stepfather’s comments on his ugliness, that he was also “attacking my real, and unknown, father.” But when as a child he saw that face in the streets it had another significance for him. He knew somehow, without being able yet to articulate it—that would take many years—that his physical appearance need have no effect on what he would do in life, that if his mother was “ugly,” then even “ugliness” could be beautiful.

For the young James Baldwin this was an important moment of self-realization. Once again he was playing a significant role in a metaphorical and sociological drama. Children believe what their parents tell them, and oppressed minorities constantly face the danger of believing the myths attached to them by their oppressors. In time Baldwin was to understand that his “ugliness” was his stepfather’s problem, that his stepfather’s “intolerable bitterness of spirit” was the result of his frustrations, that his need to humiliate those closest to him was, in fact, a reflection of the hatred David Baldwin felt towards himself as a black man: “It had something to do with his blackness, I think—he was very black—with his blackness and his beauty, and with the fact that he knew that he was black but did not know that he was beautiful.” And “he was defeated long before he died because, at the bottom of his heart, he really believed what white people said about him.”

There were times in Baldwin’s adolescence when he nearly came to blows with his stepfather. They fought because he read books, because he liked movies, because he had white friends. For Reverend Baldwin all these interests were a threat to the salvation which could only come from God. But his bitterness and hardness offended even the “saints” of the church, and he became less sought after as a preacher. In his late years he was wary of his own family, going so far as to suspect them of wanting to poison him. His children “had betrayed him by … reaching towards the world which had despised him.” David, a son by an earlier marriage, had died in jail. That David was to be James Baldwin’s model for the many fictional “brothers” who would suffer at the hands of the white “law”—Richard and the first Royal in Go Tell It on the Mountain, Fonny in If Beale Street Could Talk, Richard in Blues for Mister Charlie, for example. Sam, another son by the earlier marriage, had long since left home, and in spite of countless desperate letters from the father, dictated to the despised stepson, he saw his father next only as he lay dead in his coffin.

Sam, too, made a deep impression on his young stepbrother. Baldwin remembered in No Name in the Street how as a child he had been “saved” by Sam from drowning, and how he had learned that day “something about the terror and the loneliness and the depth and the height of love.” He never stopped longing for a repetition of that love. Sam was re-created metaphorically in several strong protective older brothers to more delicate and artistic characters in Baldwin’s fiction: Elisha is an older “brother in Christ” in Go Tell It on the Mountain, Caleb and Hall are actual brother-protectors for the autobiographical Leo and Arthur in Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone and Just Above My Head, respectively.

Eventually Reverend Baldwin lost his job, and in 1943 he was committed to a mental hospital, where he died of tuberculosis. It took many years for James’s emotions to catch up with his intellectual understanding of his stepfather and his plight. But he never stopped thinking or talking about him, and it is worth noting that his first book and his last were partly dedicated to him. In a late work, The Devil Finds Work, he remembers

the pride and sorrow and beauty of my father’s face: for that man I called my father really was my father in every sense except the biological, or literal one. He formed me, and he raised me, and he did not let me starve: and he gave me something, however harshly, and however little I wanted it, which prepared me for an impending horror which he could not prevent.

Baldwin came to see that this man, who frightened him so much that “I could never again be frightened of anything else,” was a victim of a morally bankrupt religion, a morally bankrupt society, that he was a black parody of that bankruptcy. He was to realize that in the context of such bankruptcy, the life of David Baldwin, Sr.—the attempt he had made to protect his children and to retain his dignity—had been “an act of love.” If he was incapable of showing affection, it was because he could not love himself. And if he was hard on Jimmy, he was hard on the other children, too. Tied to an ideological lie that he could not recognize, he was not, finally, to be blamed. And on Sunday morning, dressed in his three-piece suit, his Panama Stroller, his cuff links, spats, and turned-down collar, he was the picture of a longed-for pride and dignity. He was a father from another time, behaving according to another code. If that code could not work for the Baldwin children, if their real father was the one who in his pajamas paced the floor each night mumbling biblical verses—“Set thy house in order … as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord”—venting his frustrations as a beaten man, they still longed for his approval, and they still admired the father he might have been.

That Baldwin did manage to come to terms with his stepfather is due in great part to the other significant influence of his early life, his mother. He did not write a great deal about or speak much about his mother, but when he did either, it was with deep feeling and admiration. If, in his use of his own life for metaphorical purposes, his stepfather was the archetypal victim of the “chronic disease” of racism, his mother was the embodiment of the nurturing antidote to that disease. One of Baldwin’s very first memories was of his mother holding up a piece of black velvet and saying softly, “That is a good idea.” For a long time the boy thought that the word “idea” meant a piece of black velvet. He often spoke of her smile—“a smile which she reached for every day that she faced her children (this smile she gave to no one else), reached for, and found, and gave … the smile counselled patience.” When asked in several interviews towards the end of his life to describe what his mother meant to him, Baldwin usually answered by remembering something she had said to him in his teens: “I don’t know what will happen to you in life. I do know that you have brothers and sisters. You must treat everyone the way I hope others will treat you when you are away from me, the way you hope others will treat your brothers and sisters when you are far from them.” Berdis Baldwin constantly reminded her children that people must not be put on pedestals or scaffolds, that people have to be loved for their faults as well as their virtues, their ugliness as well as their beauty.

This was important teaching for any child, but especially for one who was to become a witness and a teacher. For Baldwin the love that he learned in part from his mother was to emerge as the central idea in a personal ideology that was to inform his later life.

In Baldwin’s eyes his mother was a protector and a maintainer of family unity. One of his childhood memories was a curious parody of that earlier memory of receiving his stepfather’s smile over his mother’s shoulder. Here again he received a look over his mother’s shoulder, but this time she had rushed in from the kitchen to separate and protect the two men from the physical consequences of violent filial hatred.

Emma Berdis Jones came to New York from Deal Island, Maryland, in the early 1920s. Much of her early life’s “journey” is suggested in the person and events surrounding Elizabeth in Go Tell It on the Mountain. Her mother had died when she was a young child. Berdis was left with her father, rowing out with him as he earned a living fishing on the Eastern Shore. When her father remarried, she moved in with her older sister, Beulah, “the only mother I ever knew.” Like so many southern blacks, including her future husband, Berdis Jones traveled North full of hope for a better life. She went first to a cousin in the Germantown section of Philadelphia and then to New York. Life was not easy, and it became more difficult when, in 1924, she gave birth to James. Eventually she found a live-in job with a wealthy family. In 1927, when Jimmy was two years old, she married David Baldwin, a man several years older than she, but a respectable clergyman who seemed genuinely willing to accept her son as his son. And soon there were more children; over the next sixteen years they had George, Barbara, Wilmer, David (named after his father and his father’s deceased first son), Gloria, Ruth, Elizabeth, and Paula.

As the oldest child, Jimmy was his mother’s “right arm,” helping, as she persisted in the “exasperating and mysterious habit of having babies,” with the diapers, with walks, with getting them bathed and bedded down for the night. When he was old enough he took his younger brothers by the hand and they would cross the bridge into the Bronx, where they could save money by buying day-old bread from the bakery where it was made. Or he took them to church for the Saturday-night prayer service and for Sunday School before the main service of the week.

An incident that took place soon after the birth of his brother David conveys a sense of the spe...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 The Harlem Life

- 2 Bill Miller

- 3 Awakenings

- 4 Beauford Delaney

- 5 Probings

- 6 The Expatriate

- 7 Lucien and the Mountain

- 8 Go Tell It on the Mountain

- 9 The Search for Giovanni

- 10 Notes of a Native Son

- 11 The Amen Corner

- 12 A Period of Transition

- 13 Giovanni’s Room

- 14 End of an Era

- 15 The Journey South

- 16 The Call of the Stage

- 17 Sermons and Blues

- 18 In Search of a Role

- 19 Nobody Knows My Name

- 20 Another Country

- 21 Africa and The Fire Next Time

- 22 The Activist

- 23 Blues for Mister Charlie

- 24 Lucien and the White Problem

- 25 Searching for a New Life

- 26 Istanbul

- 27 Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone

- 28 One Day, When I Was Lost

- 29 No Name in the Street

- 30 If Beale Street Could Talk

- 31 The Devil Finds Work

- 32 Just Above My Head

- 33 The Evidence of Things Not Seen: Remember This House

- 34 Gathering Around the Welcome Table

- Notes

- Chronological Bibliography of Printed Works by James Baldwin

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access James Baldwin by David Leeming in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Artist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.