- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What is graffiti? And why have we, as a culture, had the urge to do it since 30,000 BCE? Artist Fiona McDonald explores the ways in which graffiti works to forever compel and simultaneously repel us as a society. When did graffiti turn into graffiti art, and why do we now pay thousands of dollars for a Banksy print when just twenty years ago, seminal graffiti artists from the Bronx were thrown into jail for having the same idea? Graffiti has not always been imbued with a sense of aesthetic, but when and why did we suddenly “decide” that it is worthy of consideration and criticism, just within the past few years?

Throughout history, graffiti has served as an innately individualistic expression (such as Viking graffiti on the walls of eighth-century churches), but it has also evolved into a visual and narrative expression of a collective group. Graffiti brings to mind not only hip-hop culture and urban landscapes, but petroglyphs, tree trunks strewn with carved hearts symbolizing love, and million-dollar works of art. Learn about more graffiti artists and rebels such as: the band Black Flag, Lee Quinones and Fab 5 Freddy, Dandi, Zephyr, Blek le Rat, Nunca, Keith Haring, and more! Illustrated with stunning full-color photos of graffiti throughout time, The Popular History of Graffiti promises to be an important and dynamic addition to graffiti literature.

Throughout history, graffiti has served as an innately individualistic expression (such as Viking graffiti on the walls of eighth-century churches), but it has also evolved into a visual and narrative expression of a collective group. Graffiti brings to mind not only hip-hop culture and urban landscapes, but petroglyphs, tree trunks strewn with carved hearts symbolizing love, and million-dollar works of art. Learn about more graffiti artists and rebels such as: the band Black Flag, Lee Quinones and Fab 5 Freddy, Dandi, Zephyr, Blek le Rat, Nunca, Keith Haring, and more! Illustrated with stunning full-color photos of graffiti throughout time, The Popular History of Graffiti promises to be an important and dynamic addition to graffiti literature.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

PREHÌSTORÌC GRAFFÌTÌ

At some point in mankind’s early history, probably after we learned to stand upright and possibly about the same time as we discovered fire, we picked up a sharp object or a lump of charcoal and made a mark on another object or surface. Perhaps it was an accident, perhaps a hunter who was chipping away at a piece of flint to make a stone tool found that he was making scratches, not just a sharp edge. Maybe someone cooking meat on a fire rubbed a sooty hand over her brow and realized she’d left a black smudge. We will never know how it happened, but when it did, leaving marks on cave walls, stones, and other surfaces became an integral part of human life. Soon, drawing and painting were used to help hunters learn how to track down and kill essential meat. Tallies were used to keep track of numbers, pictograms evolved to leave messages for others, and finally cuneiform and other types of markings emerged, leading our species to writing as we know it, in its various scripts and alphabets of today. But let’s begin at the very beginning and find out where and when our first scratching and scribbling took place.

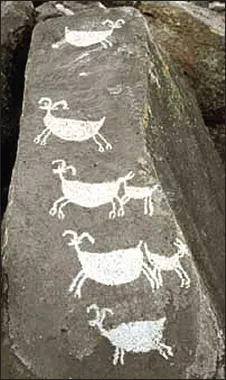

Like the Coso people of the Mojave Desert, the ancient Pueblo people of the Colorado plateau held the bighorn sheep central to their culture.

PETROGLYPHS

If we take the word “graffito” right back to its etymological origins, insisting that it refers to something being scratched onto a surface, then the best place to begin our discussion of the history of graffiti is through a particular form of rock art from prehistoric times known as petroglyphs.

Petroglyphs can be found all over the world, except in Antarctica. While most petroglyphs consist of paintings on rocks, there are some instances of images scratched into rock, though this seems less frequent. Perhaps that is due to the fact that the effort required to cut images into stone was much more laborious than simply mixing pigments and wiping or brushing them onto rock. And while petroglyphs most certainly date back more than 40,000 years, there are sadly not many cave paintings left from that long ago. The bulk of these forms of rock art begin around 27,000 years ago—many of which are found in Australia—while others are only 10,000 to 12,000 years old.

While cave paintings do not tend to depict landscape motifs, petroglyphs are thought to illustrate maps and landmarks to facilitate and communicate to other ancient humans about travel or to show where tribal boundaries were. When a petroglyph pictures a landform—a river, hill, or the like—archeologists call this a geocontourglyph.

Across the globe, petroglyphs show many similarities in style and content, even when found on continents that are far apart. One’s natural surroundings, it has been argued, provides an immediate source of inspiration—a rock is a rock whether it is in Russia or South America; a river is the same in China or Scandinavia—so the depictions of these natural landscapes don’t alter significantly from area to area. On closer examination of the glyphs, some scientists feel that the closely-related artistic styles (excluding the subject matter) might well be attributed to human migration across the continents, but there are others who see this as evidence of the “genetically inherited structure of the human brain.”

A non-prehistoric cave painting made by the San people of the Kalahari Desert, whose culture has been studied with the hope of shedding light on our early ancestors.

Many petroglyphs are thought to be the precursor of a written language system; many seem to use symbols to represent things and ideas, not just pictures of those things (which we term pictographs). Furthermore, for some scientists there has been much debate about whether petroglyphs were made consciously or whether they were the result of a person in an altered state of consciousness, such as that brought on by hallucinogenic drugs. Scientists at the Rock Art Research Institute have studied the modern day San people of the Kalahari Desert region. This culture believes that the artists of the tribe actually go into and beyond the rock face (in a trance-like state). On the other side, in the spirit world, these artists capture images that they bring back to etch into the rock. It is thought that perhaps ancient mankind may have been in a similar hypnotic state while making their incised drawings.

European Bronze Age Petroglyphs

The Vallée des Merveilles in Southern France is home to the largest collection of outdoor petroglyphs on the European continent. The majority of the markings found here are from the Bronze Age and feature tools, daggers, axes, spears, and scythes alongside horned and anthropomorphic animals, suns, stars, and a selection of geometric designs, some of which have been identified as symbols for the earth itself.

The petroglyphs at Vallée des Merveilles were discovered in 1881 by Clarence Bicknell, an amateur archeologist from Britain. Bicknell spent about five years studying the glyphs, recording them, and making drawings of them. He noted more than 10,000 of them. But it wasn’t until 1967 that a professional study was conducted of the drawings.

The overseeing archeologist for this study, Henry de Lumley, thought the glyphs were primarily the work of a Bronze Age people who worshipped a bull god.

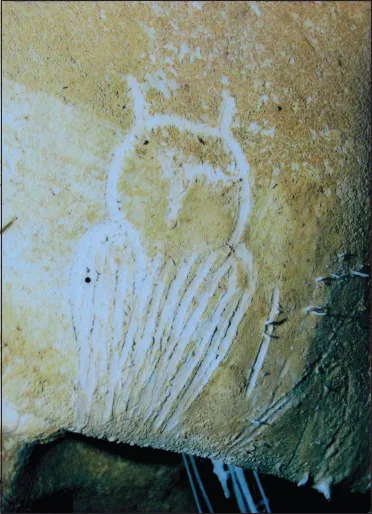

An engraving of an owl originally found in the Chauvet Caves in France, but now only seen as a reproduction in the Caves’ replica museum.

America’s Petroglyphs

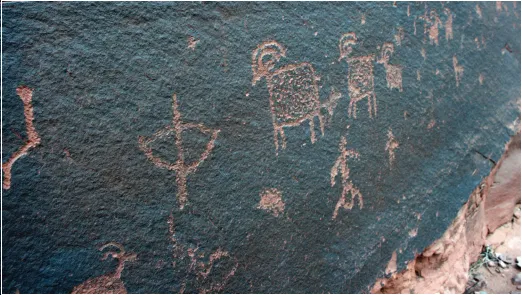

A major petroglyph area in America spreads across the Coso Range, which is situated between the Sierra Nevada and the Argus Range, covering an area of 400 square miles. Throughout this region, there are approximately 20,000 images made by Paleo-Indians, or the Native Americans. Within the Range are a number of canyons, two of which are named the Big and Little Petroglyph Canyons, and these are the galleries featuring the most extensive and well-preserved petroglyphs. These glyphs are divided into six categories: human figures (which includes anthropomorphic figures); bighorn sheep; a mixture of other animals including deer and antelope; weapons; tools; and entopic or “medicine bag” images. The glyphs are thought to be about 10,000 years old. Why they were made is not known for certain, but various theories abound. One theory proposes the glyphs were part of some magical hunting ritual, while another posits the idea that they are linked to various shamanistic rituals.

Coso figure of a stylized human accompanied by a snake and lizards.

Petroglyphs made by the ancient Coso people on a rock. It is a highly stylized piece but looks as though it might be a human figure with an elaborate headdress underneath an arch that may represent the sky.

Bighorn sheep with lambs inscribed into rock by the Coso people.

More bighorn sheep, two with horns locked in combat, made by people living in the vicinity of the Columbia River Gorge in the United States.

Nazca Lines

The geoglyphs in the Nazca Desert in Southern Peru, covering a massive area of 190 square miles, are believed to have been made somewhere between 400 and 650 AD, and are therefore relatively young compared to some of the petroglyphs found in Europe and Australia. These images are made not as etchings in the rock, but in the same way that the chalk drawings in the United Kingdom have been made. To achieve this type of rock art, the top layer of the earth is removed (in the United Kingdom it is grass, but in Nazca it is the red pebbles of the desert) and a trench 10 to 15 centimeters is dug. The ground beneath, heavy with lime, is revealed in contrast to the surrounding top layer and helps make the design stand out better. When condensation falls on the exposed lime, the mineral hardens and becomes more difficult to wear away.

These Nazca Desert petroglyphs in Peru were discovered by archaeologist Toribio Mejia Xesspe in 1927, but it wasn’t until some ten years later that any serious examination of them was made. Then, in the early 1940s, a historian from Long Island University, Paul Kosok, on a trip to study ancient irrigation systems, viewed the drawings as he flew over them in a small, low-flying plane. Of the hundreds of pictures in the desert, many of them are geometric designs, but there are also numerous depictions of living things: birds, monkeys, spiders, and plants, to name a few.

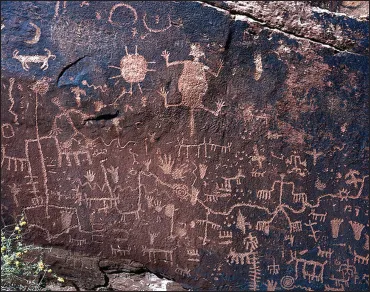

The petroglyphs on Newspaper Rock in Eastern Utah are so closely rendered that from a distance they appear to be like newsprint, hence the name. Newspaper Rock and its surroundings feature the largest known collection of petroglyphs in the world. The first are thought to have been made 2,000 years ago. The place is called Tse’ Hone in Navajo and means “a rock story.”

The precision with which this huge eagle and the other giant figures found in the Nazca Desert were made is astonishing when you realize the limited technology available to the artists. It has led to the speculation, by a limited few, that the indigenous people were given extraterrestrial help.

Kosok and the German mathematician and archaeologist Maria Reiche worked together to try to discover the purpose behind the Nazca Lines. They hypothesized that some of the lines pointed to positions on the horizon where the sun, moon, and various stars rose at particular times of the year—the solstice and equinox, for example. Reiche thought that some of the figures might also have represented constellations.

Apart from why the lines were made there remains the enigma of how they were made with such accuracy. At the end of some of the lines, the remains of wooden posts have been discovered. It is thought that these may have been anchors to tie strings to and then used to measure out the dead straight line in the manner of early surveying tools. Besides offering an explanation to the lines’ construction, the wooden posts have also helped scientists pinpoint possible dates of the creation of the lines through carbon dating.

Nazca Lima

Nazca Monkey

Yet another example of modern petroglyph graffiti. You can make out a love heart towards the bottom. There appears to be some Korean signatures on the left-hand side and a fairly recent visitor has carved the name “Jacko” to the right.

Modern-day petroglyphs scratched into rock in the popular tourist area of the Blue Mountains just west of Sydney, Australia.

Further along the same trail is an area where the graffiti is so densely carved that the whole surface is worn away.

More petroglyphs found on walking trails in the Blue Mountains. Note how they overlap and how some are obviously in languages other than English that use different characters.

Later scholars have argued over the theories of their earlier colleagues about these drawings, stating that there just is not enough evidence in the...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Prehistoric Graffiti

- 2. Graffiti in Ancient Civilizations

- 3. Medieval Graffiti

- 4. Graffiti Up Until the Twentieth Century

- 5. Modern-Day Graffiti

- 6. Street Art and Urban Artists

- 7. Beyond Traditional Graffiti

- Graffiti Glossary

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Popular History of Graffiti by Fiona McDonald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.