![]()

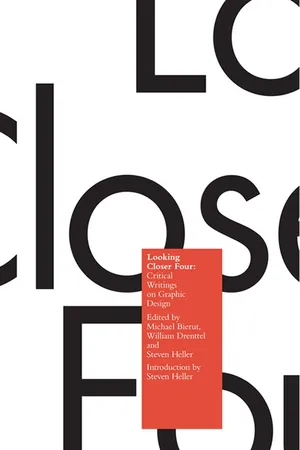

CRITICAL LANGUAGES

It was nearly twenty years ago that Massimo Vignelli took the podium at the first symposium on graphic design history, “Coming of Age” at the Rochester Institute of Technology. “Other professions, like architecture, to name one, are really sustained and forwarded by criticism,” he said in 1983. “If you open a graphics magazine from the last thirty years, there never seems to be a page of criticism, just attractive little biographies and that is it. Do you think we can go on without criticism? Without criticism we will never have a profession.” Twenty years later, thoughtful writers on design are still trying to figure out exactly what graphic design criticism is, or what it should be.

In February 2001, several hundred critics, historians, educators, students and practitioners met in New York at the American Institute of Graphic Arts’s first conference on design history and criticism, “Looking Closer,” to address the question anew. It is not an easy one. At the center of it all is the elusive nature of graphic design itself. More often that not, graphic design is ephemeral, resisting the scrutiny that an architecture critic can employ when focusing on something as public and substantial as a building. It is usually not something that is consumed by the public as a thing in and of itself, so the consumer service that restaurant and movie critics provide is not required. And, despite the rise of tropes like “The Designer as Author,” most graphic design is about someone else’s message, which makes literary criticism a questionable model.

Yet the past two decades have seen each of these models tested, retested, combined and superceded. Graphic design has been analyzed as an example of pop culture, like a rock song. It has provided fodder for theoretical academic criticism, refracted through the specialized lenses of Marxism, feminism, deconstructivism and more. In perhaps the most convincing evidence of its maturity as a field, it has even become a source for parody and satire. No one answer is final, but the quest goes on. The writers in this section focus not just on writing critically about graphic design but on writing critically about graphic design criticism. Can we go on without criticism? Obviously not. Now if only we could figure out what it is.

Michael Bierut

THE TIME FOR AGAINST

Rick Poynor

While I was thinking about this talk, I received an e-mail from a designer I know. In the subject line, at the top of the message, it said: “The time for being against is over.” When I read the message itself, I discovered that this did have something to do with its content, although only in a roundabout way. The writer was concerned not to be seen by his colleagues as an activist, in the mold of Adbusters, or some similar group. As it happens, I had never suggested he was anything of the kind, but this slightly awkward but memorable phrase—“the time for being against is over”—seems to crystallize many aspects of society and culture as we experience them today.

For the fact is that, among our own group, designers—and especially young designers—this appears to be a fairly general view. The phrase is taken from a book called The World Must Change: Graphic Design and Idealism. It’s a quote from a Dutch design student: “I do not want to separate. I have no interest in being against. I want to include. The time for being against is over.” Not long ago, a design historian of my acquaintance, a clever young woman with a Ph.D., said something very similar to me: “You can’t be against everything all the time.” I used to teach at the Royal College of Art and this issue of not being against things—the consensual feeling that we have somehow reached a point of rapprochement or healing or wholeness—came up all the time. To be against things was to be negative, and what’s the point of that? You can’t change anything by being “against things”—the world is what it is—so all that negative energy is just going to boomerang back on you in the end. By being against things, especially when most people agree that the time for being against things is over, you will only make yourself unhappy.

The whole issue came to a head for me when I sat in on a project with an environmental theme, organized by one of the other Royal College of Art tutors. He gave a spellbinding performance, unleashing a scintillating stream of facts, statistics and examples of earlier environmentally based art and communication projects. He outlined the issues and constructed a cogent and provocative set of arguments. The students—about forty of them, all studying at masters level, young adults in their mid-twenties—sat there like a bunch of sullen, unresponsive kids, offering only a few occasional, usually sarcastic remarks. Here was someone who was very definitely against things, but this display of a fiercely engaged, critical intelligence seemed to make this group uneasy. It’s not even that they argued against his point of view. Why should they? What a waste of energy, and for that matter, how uncool! The time for being against things is over.

If this is anything like the dominant view—at least among educated young people—then these do not appear to be very propitious times for any kind of criticism, let alone design criticism. Because, as I have always understood the term, to be critical involves not taking things for granted, being skeptical, questioning what’s there, exposing limitations, taking issue, advancing a contrary view, puncturing myths. On occasion, of course, the critic will take the role of supporter and advocate. He or she will seek to persuade us that some idea or thing is deserving of our full attention and merits a closer look. The critic will act as interpreter and explain some seemingly arcane aspect of culture that many or most of us don’t yet grasp and are perhaps inclined to resist. But this process of supportive elucidation will always imply its opposite: that there are objects and projects that are not worthy of our attention, that are problematic, flawed and sometimes possibly even pernicious. Any would-be critic who practices only the role of supporter and advocate, who never finds fault, sees nothing to contest, is not really a critic at all.

While it’s hugely encouraging for anyone who continues to think criticism matters that a conference like this should take place—it’s almost unthinkable, at the present time, that a British design organization would mount such an event—design criticism continues to survive in, at best, a precarious state of health. How could it be otherwise? To exist at all, criticism depends on two things: a range of suitable outlets and a body of people—the critics—to supply the criticism. We don’t have enough of either. If criticism is struggling in a wider cultural sense, if proprietors of mainstream media believe it is simply not required by most ordinary readers and viewers, and readers and viewers show every sign of endorsing this judgment (because the time for being against is over), then it would be very optimistic indeed to expect specialist trade publications aimed at practicing graphic designers to lead the critical fight-back. On the contrary, as a very young discipline, graphic design criticism needs to learn by “looking closer” at critical practice in neighboring areas. Fortunately, the critical mentality is so deeply entrenched that it still thrives in pockets elsewhere, and there are even signs of a possible renewal.

I’ll return to this later, but first I’m aware that I need to state my own position more clearly to supply the context for these remarks. The term I have sometimes used for the practice I would like to engage in is “critical journalism.” I have occasionally described myself as a “critic,” for reasons of expediency, but “critic” is a pretty strange passport description, and I really just see myself as a writer with a lasting, fairly serious commitment to design and visual culture. I engage in different ways with material that interests me, depending on the forum and audience. I certainly hope there’s always some strand of critical awareness in anything I publish—I might be wrong about that, of course—but the writing undeniably slides up and down a scale between relatively impersonal journalism at one end (though I’m not interested in doing this kind of writing) and criticism, in some notionally purer, much more personal and perhaps more academic sense at the other. Most of the time it will be strategically located somewhere near the middle of this scale—hence my use of the term “critical journalism.” It’s an attempt to combine journalism’s engagement with the moment and its communicative techniques with criticism’s fundamental requirement for a worked-out, coherent, fully conscious critical position: a way of looking at, and understanding, the world, or some aspects of it, anyway.

But to explain this fully, I need to go a little further because the kind of writing I now do, in this particular field, comes directly from my experiences as a reader going back many years. I’ve always read criticism and I’ve always read critical journalism. Much of my education and sense of the world has come from undirected, personal reading across a range of cultural fields—literature, music, social history, film, photography, fine art and other subjects. I’m sure most of you could say the same. I have always been engaged by writing that seemed to assume the existence of readers like me: people who just happened to have an interest in a subject, whatever it might be—the postwar novel, Kurt Schwitters’s collages, New German Cinema, the French Nouvelle Vague—because they took meaning and pleasure from it and believed it to be important. This writing wasn’t directed exclusively or even perhaps largely towards an audience of academic peers and students, even if the academy was often its point of origin. It wanted to discover a broader audience. It was aimed outwards at any intelligent, literate, thinking individuals, from any background, with the curiosity to undertake their own personal researches and see what they could find out.

There’s a nice term for the kind of writer who chooses to occupy this cultural position, to think in public and address the broadest possible readership—it’s “public intellectual.” One hundred years ago such a position would have been taken for granted. Intellectual discourse was a public activity accessible to any educated citizen. Fifty years ago it was still perfectly viable. Think of figures like the architectural writer Lewis Mumford, the psychologists Bruno Bettelheim and Erich Fromm, the art critic Clement Greenberg. A few months ago, the New York publisher Basic Books organized a debate on “The Future of the Public Intellectual”—you can read an adapted version on the Nation’s Web site. Four of the six panelists were academics—among them Herbert Gans, professor of sociology at Columbia University, and Stephen Carter, professor of law at Yale. The other two were critical journalists: the British writer Christopher Hitchens and Steven Johnson, co-founder of Feed magazine on the Web—more on him a bit later. Today, the public intellectual is often thought to be an endangered species. Public intellectuals were sustained by an audience of learned readers that has dwindled hugely since the 1960s, even if it hasn’t entirely gone.

Do graphic designers form any significant part of that remaining core of readers with a commitment to ideas and the independent life of the mind, expressed through the act of reading? Are they, in other words, really interested in criticism? And, conversely, are those with a commitment to ideas the slightest bit interested in graphic design? These are daunting questions, when framed in those terms, as I think you’ll probably agree.

Let’s stick to designers for the moment. For as long as I have been writing about graphic design, I have heard it repeated like a mantra—by designers themselves and, more worryingly, even by one or two design writers—that designers as a professional group, as a type of person, “don’t read.” Not that they don’t read history, or philosophy, or literature. But that they don’t read, period. Not even the undemanding lifestyle magazines they like to “graze” to catch up on the latest styles and trends. As someone who has voluntarily chosen to write about this material, and could have done something else instead, I suppose that makes me a pretty extreme form of masochist. Why go on with it? First, because I don’t really believe it. I suspect that the designer who pronounces blithely that “designers don’t read” is often just talking about himself (it usually is a “him,” too). I know too many designers who do read and care about writing to accept the generalization, even if it holds true for the majority. Second, because it struck me quite early on, as someone then writing about architecture, art and three-dimensional design, as well as graphics, that graphic design was a genuinely fascinating area of study. In art or architecture, it sometimes feels as though all that remains is to add footnotes and corrections to the huge corpus of criticism, theory and history that already fills the libraries. Graphic design, by comparison, was still relatively unknown, uncharted territory. There was work to be done. There was the excitement of discovery and getting to things first—a huge motivation for any writer, whether engaged in journalism or criticism.

The other thing that struck me—and this is where these points connect up—is that, given the relatively open, unprofessionalized status of graphic design writing, as well as the nature of its potential audience, it ought to be possible to find a way of writing about the subject that corresponded with my own preferences as a reader. My models here, in many ways, were the music press, as it was in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and the serious film press, as it is even now. Both of these areas had hugely knowledgeable, talented, independent writers, who earned a living from their enthusiasms by writing critical journalism for a broad, smart, demanding readership that might include academics, but was open to anybody who shared the writers’ perspectives, passions and tastes.

I hesitate to give too many examples because, in my case, they are necessarily mainly British. I’m thinking of the kind of writing you might have found in the music paper New Musical Express during the punk and post-punk years, or the film magazine Sight and Sound at any point in the last four decades. The sort of prose produced, in America, by a music writer like Greil Marcus or film writers like Jim Hoberman and Amy Taubin (both of whom write for Sight and Sound). Books like Ian MacDonald’s extraordinary, meticulous, track-by-track study of the Beatles, Revolution in the Head, which teases a revolution in sensibility from the song-writing process. Or Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming, which sees British society refracted through punk rock. Or David Thomson’s brilliant Biographical Dictionary of Film, one of the truly essential film books, lovingly crafted and periodically updated by a master essayist who has much to teach any would-be critic operating in any cultural discipline. These writers are both hip and scholarly, generous but rigorous, and they make the reader feel that their subject truly matters. It always seemed to me that graphic design, as a ubiquitous form of popular culture, could be written about in much the same way and that this was the strategy, if one could pull it off, that would be most effective in winning readers.

And here we return to the nub of the problem. For who, indeed, are the readers? Well, as we all know, in the main they are people involved in design—the ones who can be bothered to read, that is. Design has many beautifully produced, highly professional publications, but, by and large, they are not read by non-designers, nor do they expect to be. That’s rather strange, though, if design really does have the cultural importance and meaning that we constantly tell ourselves that it has. It’s like a music press read only by musicians, or a film press read only by filmmakers. Film and music publications are read by professionals, but the whole point of these magazines is that they address a broad, general readership. Design magazines, however, are mostly trade publications, and you wouldn’t expect ordinary members of the public to read Hotel and Catering Weekly or Liquid Plastics Review. Yet, to judge by the look of them, design magazines aspire to be very much more than this: they are lavish, confident, magnificently visual. You can even buy them on certain newsstands. They win press awards. The problem is that no matter how good some of these publications are, the fact that they address and serve a professional audience of designers must inherently limit their ability to criticize their subject matter. I’m generalizing, of course, because I do think some are much more genuinely critical than others, but still there are certain lines that are rarely if ever crossed.

Yet, at the same time, as anyone who’s tried it well knows, finding outlets for graphic design writing outside its dedicated press—outlets which could, in theory, allow much greater freedom to be critical—is always a struggle. Earlier this month, Jessica Helfand, a designer who also writes regularly, published a big piece about Milton Glaser in the Los Angeles Times, based on a review of his book Art Is Work. It was a rare and notable exception. I recently wrote a longish essay about graphic authorship for one of the British Sunday papers. Amazingly, they ran it on the cover of the culture section, but it was touch and go for a while. There were real concerns behind the scenes, among some of the editors, that it was “too specialist,” even though I had done everything I could to “open up” the subject for the general reader, and it was pegged, opportunistically, on the publication of Bruce Mau’s heavily promoted book, Life Style, and several appearances by him in London in the course of the following week. I automatically included a brief explanation of graphic design near the start of the piece, and I notice that Jessica did exactly the same thing. Imagine a review of a novel that felt obliged to begin with an explanation of “fiction,” or a feature about art that felt it was necessary to explain the mysterious craft of “painting.” Graphic design may be everywhere, but for c...