- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

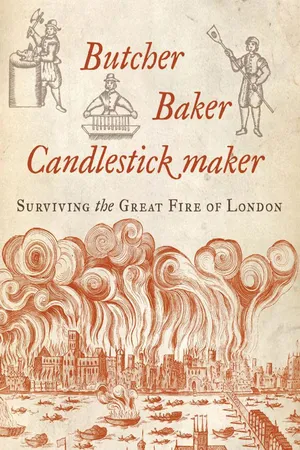

Hazel Forsyth delvesin to never-before-studied primary sources to shed light on thedramatic aftermath of the disaster and reveal the very personalstories of the people who pieced their lives together in its wake. Bydocumenting the tradesmen, from apothecaries and chandlers toshoemakers and watchmakers, Butcher, Baker, Candlestick Makertells a story of loss and resilience and illuminates how the citywe know today rose from the ashes. Beautifully illustrated withexquisite fabrics, candle snuffers and other fascinating imagesassociated with the trades of the time, we are treated to a visualfeast, an evocative reminder of life before and after the Great Fire.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Butcher, Baker, Candlestick Maker by Hazel Forsyth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A–Z of Trades

‘people … are at their wits’ end, not knowing how to carry on trade by reason of the great fire in London.’—Robert Scrivener, 17 September 16662

This section is arranged in alphabetical order by trade. It is a fairly even distribution, though some letters are better represented than others: there are no trades with the initial letters Q, X or Z; the letters K and R are problematic; and it just so happens that a number of trades have the initial letters C, P, s and T in common. Only those crafts and trades that have a link to the fire have been included, and the surviving evidence has determined the final selection. Sometimes the connection to the fire is obvious; in others it is a little more tenuous. There are 31 trade headings, but some trades have been grouped together or subsumed for convenience, either because they have a natural affinity or because the trades were more or less indivisible in practice: so booksellers are included with stationers; mercers with silkmen; drapers with clothworkers; water-pipe borers with plumbers; brickmakers with tilemakers. The term ‘upholsterer’ has been used rather than the contemporary ‘upholder’, and the various tobacco trades – tobacco-cutter, tobacco-presser, tobacco pipe-maker and tobacco seller – which were sometimes separate specialisms, but more often than not combined, have been grouped together under the heading ‘tobacconist’. Wax chandlers are incorporated with tallow chandlers because most of the relevant evidence is balanced towards the tallow-chandlery side of the trade. It is necessarily something of a patchwork pattern, but taken together the sample does convey something of the occupational diversity of London in the pre- and post-fire period and provides a snapshot of Londoners’ responses and reactions to the fire, and the kinds of goods and possessions lost and recovered.

These Tradesmen are Preachers in the City of London or A Discovery of the most dangerous and damnable tenets that have been spread within this few years; by many erroneous, heretical and mechanic spirits (London, 1647). This satirical broadside lampoons the idea of untrained artisans preaching in the capital.

Apothecary

‘[Valerian,] an excellent medicine … against nervous affections … trembling, palpitations, vapours and hysteric complaints.’—Nicholas Culpeper, The Complete Herball, 1653

Amber was considered to have great therapeutic benefit. (left) The sheer quantity and variety of foreign coins in London created confusion for legitimate traders and opportunities for the unscrupulous. Scale balances with an accompanying box of stamped brass coin weights, for both foreign and domestic issues, were used by merchants, tradesmen, physicians and apothecaries to ensure that they were not short-changed.

The slow process of recovery from the shock and horror of the fire must have sparked a brisk trade in soothing simples, salves and drugs for burns and nervous complaints. References to injuries are few, but one commentator mentioned those ‘burnt, starved and disabled to make and follow theire trades’, and the Barber-Surgeons’ Company gave 10 shillings to a seaman who was injured when he climbed onto the roof of their Anatomy Theatre to quench the flames.3 Specialist manuals such as De combustionibus, the first book devoted to burns and their treatment, published in Basle in 1607, were perhaps avidly read, and the apothecaries would have drawn upon their vast knowledge of herbs and simples to relieve pain and discomfort. The apothecary Nicholas Culpeper recommended the bruised leaves of St Peter’s wort and alkanet to ease ‘burnings by common fire’; and fresh ivy leaves boiled in wine and applied as a plaster, he suggested, were ‘effectual to cure all burns and scalds, and all kinds of exulcerations coming thereby’.4

The sheer range of pills, potions and lotions sold in mid-seventeenth-century London was staggering.5 Therapeutic preparations of all kinds are described in herbals and pharmacopeias, but detailed evidence for trade practice is comparatively slight. The records of the Society of Apothecaries mention the ‘herbarizing’ excursions to the fields around the City to gather plants for drugs and cosmetics; they refer to periodic inspections of apothecaries’ and druggists’ shops, and, more rarely, to an improper use of ingredients. In 1664, one man (unnamed) was fined 10 shillings for ‘haveing ruberb & sirop of Violetts bad’ and for making and selling London treacle (used as a preventative against plague) without permission.6 But the best evidence comes from inventories which provide detailed lists of the drugs and other wares in apothecaries’ shops. When Theophilus Dyer’s stock was appraised for probate in 1663, for instance, he had an old still for distillation, a lead ‘bottom’ used as a base for the still, and a boiling pan in his kitchen, along with other household goods. The yard held an ‘old stone mortar’ with his ‘signe and signe post’, and the shop stock comprised several purging electuaries made from dried, sieved and finely powdered herbs, flower petals, seeds and roots mixed with warm clarified honey; various drug ingredients in nests of small, medium and large boxes; drugs and several kinds of seeds in barrels; several sorts of ‘old syrupps’, conserves, oils, unguents and ‘divers masses of Pills’. The working tools included a brass mortar and pestle, and three more ‘mortars blacke’, as well as an old iron furnace. There was a ‘short ladder’ to reach items stored on the highest shelves, several ‘old bookes’ and a desk in an adjoining closet. Apart from wooden boxes, there were flasks and pharmaceutical glasses and several kinds of earthenware ‘galley pots’ or drug jars.7 The sizes of these jars are not specified, but surviving examples range in size from minute pots little bigger than a thimble, designed perhaps for a special compound or a single dose of a prescription drug, to large containers holding a quart or more of dry or wet ingredients. Many of the vessels were made in standard sizes with a slightly waisted girth to enable the pot to be handled and easily removed from a stacked shelf. Some were plain white, some had polychrome banding and chevron patterns, others were marked with the proprietary name of the product.

The apothecary Peter Culley, who died two months before the fire, either manufactured drugs on-site or stocked supplies for others, because he had a warehouse full of drugs behind his shop in the parish of St Andrew Undershaft. The shop itself, subdivided into a retail, storage and working space, was filled with parcels of ‘simple and compound’ waters and syrups, all sorts of conserves and electuaries, oils, cordials, powders, pills and plaisters, spices and ‘chemical preparations’, as well as several packets of drugs stacked on shelves and in assorted cupboards nearby. There were glasses, gallipots, a mortar, stills, and various other utensils, and behind the counter in the ‘back shop’ were other boxes, barrels and a still pot. The warehouse drugs were piled onto shelves and one of the garrets above, doubled up as a store for five tubs, 12 old boxes, odd items of lubber and some ‘bladders’ which were used to cover the rim of drug jars and distillation vessels to protect the contents from drying out. The bladders were often punctured so that ‘excrementitius and fiery vapours may exhale’, but they were not considered suitable for glass or stone syrup pots ‘unless you would have the glass break and the syrup lost’.8 The combined value of Culley’s shop and warehouse stock came to £253 7d.9

Decorative slabs were used by apothecaries as a shop sign and for rolling out pills and ointment pastes. (left) The inscription ‘s: TVSSIL’ for Syrupus Tussilago or Syrup of Colt’s Foot appears in pharmacopoeias between 1618 and 1677. It was reputed to be good for a dry cough. The unicorn head motif is rare; this jar might have contained plague water with ground hart’s horn to prevent ‘swoonings, faints, fevers and convulsions’.

Evidence for the fire’s impact on trade and the lives and businesses of individual apothecaries is rather harder to find. There is a terse but rather telling entry in the probate inventory for the apothecary Michael Markland, which reads: ‘Item. Paid for the charges of removing the Testators household goods plate ready money & other things in the tyme of the late dredfull fire – £5.’ This odd scrap of evidence conveys so much and yet so little. Where did he live? Was he able to resume his trade? Did the fire mark the end of his career and destroy his life? The absence of detail is all the more remarkable since it was written two and half years after the fire on 11 March 1669.

Some of the most intriguing evidence for the apothecaries’ trade in the immediate pre- and post-fire period comes from two rather surprising sources. The first occurs in a case brought before the Mayor’s Court in London on 29 September 1668. The deponent was Daniel Van Mildert, a 25-year-old Dutch merchant based in Homerton in Hackney, who testified that he had sold two cases of drug ingredients to Thomas Watson, an apothecary in the City, on 25 May 1664. Both cases had come from John Cloppenburg in Amsterdam, for whom Van Mildert acted as an agent. The first contained 17¾ lb of ‘trimed-agric’ (possi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Note to readers

- The lamentable Fire

- A–Z of trades

- Notes & references

- Acknowledgements

- Image sources

- eCopyright