eBook - ePub

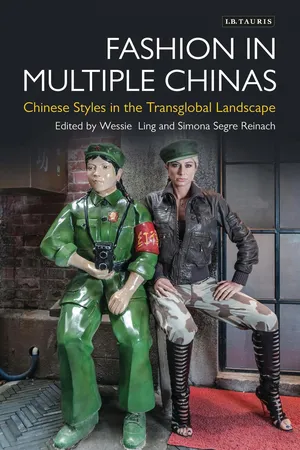

Fashion in Multiple Chinas

Chinese Styles in the Transglobal Landscape

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fashion in Multiple Chinas

Chinese Styles in the Transglobal Landscape

About this book

Much has been written about the transformation of China from being a clothing-manufacturing site to a fast-rate fashion consuming society. Less, however, has been written on the process of making Chinese fashion. The expert contributors to Fashion in Multiple Chinas explore how the many Chinese fashions operate across the widespread, fragmented and diffused, Chinese diaspora. They confront the idea of Chinese nationalism as `one nation', as well as of China as a single reality, in revealing the realities of Chinese fashion as diverse and comprising multiple practices. They also demonstrate how the making of Chinese fashion is composed of numerous layers, often involving a web of global entanglements between manufacturing and circulation, retailing and branding. They cover the mechanics of the PRC fashion industry, the creative economy of Chinese fashion, its retail and branding, and the cultural identity of Chinese fashion from the diasporas comprising the transglobal landscape of fashion production.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fashion in Multiple Chinas by Wessie Ling, Simona Segre-Reinach, Wessie Ling,Simona Segre-Reinach in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Fashion & Textile Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

FASHION-MAKING IN THE TRANSGLOBAL LANDSCAPE

Wessie Ling and Simona Segre Reinach

READING CHINESE FASHION

Much has been written about the transformation of China from a clothing manufacturing site into a fast-rate, fashion-consuming society. However, little investigation has been made into the making of contemporary Chinese fashion, a process that often involves a borderless entanglement from manufacturing to circulation, to retailing and branding. Recent studies on contemporary Chinese fashion have allowed us some reflection on the subject. Central to these studies is the attempt to make sense of it in the definition of modernity, identity, cultural and creative economy and global circulation. Revealed within are the tremendous cultural and economic dynamics that are at times challenging to articulate. Precisely, what is Chinese fashion? Whose Chinese fashion is it? Why does it matter – and to whom? These are just some of the questions to unpack before Chinese fashion can be discussed and analysed.

At first glance, the formation of contemporary Chinese fashion offers a compelling example of cultural, economic and political entwinement across the globe. On closer examination, Chinese modernity in the twenty-first century cannot be merely underscored by Chinese hybridity typified between China and the West. Rather, it entails a power dynamic between China and the rest of the world, whereby constant negotiation is expected. While some consider that fashion designers are more concerned with the aesthetic of surfaces, rather than the specifics of cultural context and the logic of politics,1 the case of China, however, reveals cultural and political context as the very defining point of the making of its fashion.2

There is no linear way to read the formation of contemporary Chinese fashion, despite efforts in this direction, for different reasons both the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the globalised (Western) fashion systems.3 Chinese fashion consists of multiple and, at times, contradictory processes in its making. The first preconception often goes to the absence of fashion in pre-Reform era, putting the debate between fashion and costume at the forefront. The post-colonial theory of fashion studies,4 however, has demonstrated in various ways that fashion was not separate from costume – that is the weakness of a binary take; costume versus fashion, tradition versus modernity and the transformation of what once went under the label of ‘costume’ within the logic of global designers from different backgrounds. Studying the process of fashion-making in China suggests going further, applying a more embracing approach in contemporary fashion theory; that is, to consider the multiple and interrelated factors entailed in the process under the rubric of a transglobal landscape. Developing concordantly is the growing academic field of fashion in which it is taken as a major topic of enquiry in social and cultural theory, and analysis devoted to it is the understanding of this complex arena.5 In this volume, China is taken as an example to unpack the complexity of: (1) identity formation in the making of contemporary fashion; and (2) the dynamics of fashion-making in the transglobal landscape.

CHINESE FASHION IN SCRUTINY

When it comes to Chinese fashion, questions on its stereotypical image, history and varieties arise that demand scrutiny for understanding of the subject. The need to unpack has led us to propose three interconnected concepts: (1) common belief; (2) time; and (3) space. The first concerns the conflicting perceptions that the West and China itself have on Chinese fashion; the second is the debate on the ‘origin’ of contemporary fashion in China and its relation to the past; the third is the geographic and cultural diversity of Chinese creativity. At heart within this conceptual framework are the common belief that Chinese fashion refers only to material production, the conflicting relationship between Chinese fashion and its historical past, and the transcultural, transglobal map that defines contemporary Chinese fashion(s), all of which intertwine and cross paths with one another. Discussing one topic, as individual chapters will show, opens up the others; it is precisely their interconnection that gives rise to the usefulness of this approach.

Common belief: material versus symbolic production

A hegemonic construct of the Eurocentric matrix, reinforced by the narratives typical in the age of fashion outsourcing, distinguishes between fashion and garment production, disavowing any creativity – which is the very essence of fashion – by the countries devoted only to the manufacturing of garments for the global market.6 China is, of course, the most relevant in this case. The split between material and symbolic production of fashion,7 postulated by Western fashion systems as a tenet of the globalised industry, is in fact not easy to trace, especially in China. The two are interconnected, impossible to disentangle. Since 1978, Chinese engagement in making in volume and signing international agreements – from joint ventures to all forms of global collaboration – has contributed to the image of China as a manufacturing site. In fact, the very reason that makes China the factory of the world also made it possible to attain the level of high-quality production in a short space of time. The case of China is further complicated, with respect to other outsourcing production venues, by the fact that since the year 2000 the country has become the major market for international brands, many of which are also manufactured in China. Since the first years of the Open Door Policy, producing fashion on both the material and symbolic level represented a real challenge for China; not only was it eager to re-align itself with the Western world but also to excel as a country that can master aesthetic knowledge8 as a form of soft power for nation branding/building,9 as well as profit from the creative economy.10 Leading to this is the conflicting (cultural) identity of Chinese fashion. Since the Beijing Olympic Games in 2008 and the Shanghai Expo in 2010, the development of the cultural industry has become as much a priority for the Chinese government11 as has upgrading the quantity and quality of production and foreign investments. China is very keen to earmark creativity as a distinguished progression in the post-Reform era, thus fashion, as part of the cultural industry, has been taken as a fast route to achieving such national, and henceforth global, recognition. Apparent in the context of China are the parallel development of material and symbolic production in fashion and the birth of a global consumer society.

Time: is there fashion before 1980s China?

Although it is understood that the concept of fashion in China only started in the early 1980s,12 the history of fashion in China under the Cultural Revolution and before 1949 had a significant impact on the development of contemporary Chinese fashion,13 as well as that outside of the PRC.14 The imposition of the meaning of fashion as defined by Western scholars15 confused rather than clarified the formation of Chinese fashion. When the Eurocentric view of costume versus fashion and the subsequent debate between tradition and modernity16 are imposed onto China, a more complicated picture is revealed. It is not useful to uphold the opposition between the modernity of Western fashion and the traditional fixed costumes found in other sartorial systems, at least for China. It is not a valid and heuristic model in particular dynamics between so-called costume and fashion as expressed in different historical periods of China. From early 1900 to 1949, hybridity between East and West was at its height. Instead of opposing European fashion to Chinese costume, there was a tendency to forge a mixed aesthetic, totally embedded into and responding to the troubled politics of the time.17 During the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), there was a(n) (almost) complete block on China’s relations with the outside world and fashion was considered a bourgeois outcome. A new sartorial image – that is, the Mao suit and its (unsuccessful) feminine version, the Jiang Qing dress18 – aimed for both an alternative to Western modernity and the rejection of Chinese traditions. The attempt to despise Western bourgeois culture led to what could be seen as ‘the strange world of socialist fashion’.19 In the first years following the Open Door Policy (1978), the time lag of fashion trends represented both renewed Chinese interest in fashion and the constraints on them in mastering its language. At the beginning of the 1980s, the sole model on which to reconstruct Chinese fashion appeared to be a somehow naive blend from Hong Kong, Japan, Korea and Europe. With the expiration of the Multi-fibre Agreement (MFA) in 2005, the flow of cheap Chinese garments to Europe and the USA started to disrupt the Euro-American fashion industry, forging the image of China as the enemy of the liberal (Western) economy as well as its position as the world’s manufacturing site.

Space: one versus multiple China(s)

Nonetheless, the influence of sartorial traditions in nearby Chinese cities and settlements such as (post-)colonial Hong Kong, the diasporic Chinese production in Taiwan, Singapore, Macau and the USA are all part of the reality of contemporary Chinese fashion. The more powerful China becomes in the global arena, the more the interaction there is from other Chinese regions. Adding to this is the stratification of Western fantasies about China, which has, by and large, a significant part to play in the façade of contemporary Chinese fashion. All of which has shaken, redefined and reshaped its formation. Even the complex geography of Chinese settlement has complicated the meanings of the apparently fixed garments such as the infamous qipao, the controversial ‘national’ dr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Fashion-Making in the Transglobal Landscape

- Part I: People’s Republic of China’s Fashion Industry

- Part II: Fashion in Other Chinas

- Part III: Chinese Fashion and the West

- Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index

- eCopyright