- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"The compelling story of a colony besieged by meteorological, epidemiological, economic, and manmade catastrophes only to arise like the phoenix." —Orville Vernon Burton, author of

The Age of Lincoln

During South Carolina's settlement, a cadre of men rose to political and economic prominence, while ordinary colonists, enslaved Africans, and indigenous groups became trapped in a web of violence and oppression. John J. Navin explains how eight English aristocrats, the Lords Proprietors, came to possess the vast Carolina grant and then enacted elaborate plans to recruit and control colonists as part of a grand moneymaking scheme. But those plans went awry, and the mainstays of the economy became hog and cattle ranching, lumber products, naval stores, deerskin exports, and the calamitous Indian slave trade. The settlers' relentless pursuit of wealth set the colony on a path toward prosperity but also toward a fatal dependency on slave labor. Rice would produce immense fortunes in South Carolina, but not during the colony's first fifty years. Religious and political turmoil instigated by settlers from Barbados eventually led to a total rejection of proprietary authority.

Using a variety of primary sources, Navin describes challenges that colonists faced, setbacks they experienced, and the effects of policies and practices initiated by elites and proprietors. Storms, fires, epidemics, and armed conflicts destroyed property, lives, and dreams. Threatened by the Native Americans they exploited, by the Africans they enslaved, and by their French and Spanish rivals, South Carolinians lived in continual fear. For some it was the price they paid for financial success. But for most there were no riches, and the possibility of a sudden, violent death was overshadowed by the misery of their day-to-day existence.

During South Carolina's settlement, a cadre of men rose to political and economic prominence, while ordinary colonists, enslaved Africans, and indigenous groups became trapped in a web of violence and oppression. John J. Navin explains how eight English aristocrats, the Lords Proprietors, came to possess the vast Carolina grant and then enacted elaborate plans to recruit and control colonists as part of a grand moneymaking scheme. But those plans went awry, and the mainstays of the economy became hog and cattle ranching, lumber products, naval stores, deerskin exports, and the calamitous Indian slave trade. The settlers' relentless pursuit of wealth set the colony on a path toward prosperity but also toward a fatal dependency on slave labor. Rice would produce immense fortunes in South Carolina, but not during the colony's first fifty years. Religious and political turmoil instigated by settlers from Barbados eventually led to a total rejection of proprietary authority.

Using a variety of primary sources, Navin describes challenges that colonists faced, setbacks they experienced, and the effects of policies and practices initiated by elites and proprietors. Storms, fires, epidemics, and armed conflicts destroyed property, lives, and dreams. Threatened by the Native Americans they exploited, by the Africans they enslaved, and by their French and Spanish rivals, South Carolinians lived in continual fear. For some it was the price they paid for financial success. But for most there were no riches, and the possibility of a sudden, violent death was overshadowed by the misery of their day-to-day existence.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Grim Years by John J. Navin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Two

Carolina

Even before slaves on Barbados harvested sugarcane, many colonists in British North America employed Native Americans and Africans in their fields, shops, and homes.1 After the Restoration of the monarchy, the British seized or established additional colonies on the American mainland, all of which would import enslaved Africans.2 The emergence of slavery in North America may have been inevitable, but its persistence was not. The first colonies to legalize slavery would also be the first to eradicate it, partly because of cultural imperatives, but largely because voluntary immigration and natural increase provided sufficient manpower. Slavery became most firmly entrenched in colonies where African laborers generated the greatest profits and where proprietors and administrators allowed or even encouraged their importation. In short, regardless of location, seventeenth-century British colonists made decisions based on their needs and opportunities, oftentimes ignoring the human cost, especially when other races were involved.

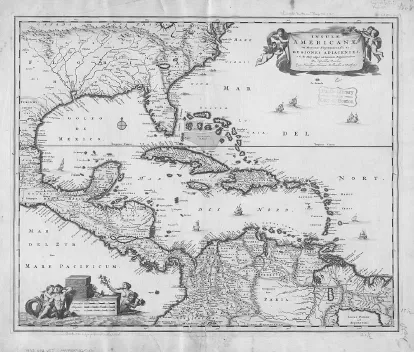

Nicolaes Visscher, Insulæ Americanæ in Oceano Septentrionali ac regiones adiacentes : a C. de May usque ad Lineam Æquinoctialem, Amsterdam, c. 1692. Map from Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library Digital Collections.

The prevalence and prominence of Barbadian immigrants in early South Carolina meant that the colony was likely to include enslaved Africans from the outset. But those Barbadian roots also meant that many colonists were familiar with the dangers posed by discontented whites as well as rebellious blacks; in the 1650s sugar barons had fortified their houses to repel attacks “by the Christian servants or negro slaves.”3 In 1675 news from Virginia and other colonies would only exacerbate those concerns. South Carolina’s leading men realized that their prospects and the colony’s very survival depended on the ability to combat external threats and to preserve internal order. Those capabilities hinged on the tenor of the colony’s relationships with Native American neighbors and on its demographics—enslaved Africans provided crucial labor but a free white majority meant greater security. The wild card was profit, the scent of which seemed to render otherwise sane men insensible.

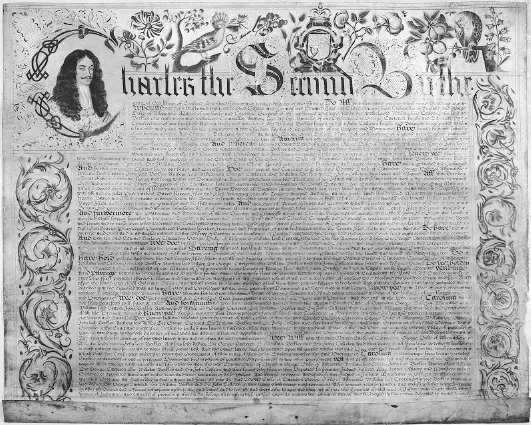

In 1661, the same year Barbadian lawmakers took steps to protect their lives and fortunes by passing An Act for the better ordering and governing of Negroes, the coronation of Charles II took place at England’s Westminster Abbey.4 Two years later, the new king named eight of his aristocratic supporters “Lords Proprietors” of the Province of Carolina, a massive tract that extended from Virginia to Florida and westward to the Pacific.5 The grant encompassed thousands of square miles populated by indigenous groups who, in an era of European expansion, could be pushed aside, exterminated or, better yet, exploited in any number of ways. To the south, thinly manned Spanish Florida represented as much a target as a threat to potential English settlers.6 To the west lay territory claimed by France, “unimproved” and poorly defended except by their Native American allies. In short, the land now called “South Carolina,” as well as its inhabitants and neighbors, was ripe for the plucking. And then there were out-of-luck Englishmen, Scots, Irish, and downtrodden refugees from other European nations, all ripe for the plucking as well. The Province of Carolina would be of little value if the proprietors could not populate it with drones that were convinced that it was in their best interest to undertake the backbreaking work involved in establishing a profitable colony. Of course there were also “uncivilized” creatures, neither white nor Christian, who could be compelled to serve at the end of a whip, or worse.7 All things considered, it was good to be a kingmaker.

The proprietor who engineered the massive Carolina grant was John Colleton, a royalist who fled to Barbados after the execution of Charles I. Upon his return to London, Colleton was knighted and appointed to the Council for Foreign Plantations. In that capacity, he became acquainted with a number of influential men who shaped England’s colonial strategy and policies. They included Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon and minister to Charles II; John Berkeley, 1st Baron Berkeley of Stratton, and his brother, Sir William Berkeley, governor of Virginia; Sir George Carteret, vice chamberlain of the royal household and treasurer of the navy; and Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper, the forward-thinking 1st Earl of Shaftesbury. To secure the Carolina charter, Colleton also reached out to his cousin, George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle, and to William Craven, 1st Earl of Craven. The assemblage was unmatched in terms of political acumen and experience in colonial affairs.8 As Lords Proprietors of Carolina, they were granted powers normally reserved for the monarch. In Leviathan Thomas Hobbes reasoned that “men have no pleasure, (but on the contrary a great deal of grief) in keeping company, where there is no power able to over-awe them all.” Charles II granted the proprietors sufficient authority to ensure that Carolina would proffer both “pleasure and profit.”9 Shaftesbury was so enamored of the possibilities that he came to refer to Carolina as his “Darling.”10

Carolina Charter of 1663, first page. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

By 1663 colonies in North America and the West Indies had shown that furs, tobacco, sugar, and other exports could generate considerable revenues for planters, agents, merchants, and royal coffers. However, joint stock companies and other investment schemes that financed pathbreaking colonizing ventures had met limited success: the Virginia Company of London, the Merchant Adventurers who sponsored Plymouth colony, Sir William Courteen’s syndicate to promote settlement on Barbados, and the Puritan backers of Providence Island were among the many English entrepreneurs who lost money on transatlantic enterprises.11 Not surprisingly, the Lords Proprietors’ first instinct was to encourage ventures in Carolina where colonists would bear the costs and risks of settlement, rewarding their distant landlords through a system of quitrents. However, false starts involving immigrants from Virginia and from New England (who found the Cape Fear area “scandalous”) convinced the proprietors that a different, more proactive approach was required.12 The planting of colonies was no undertaking for the faint of heart, the uninformed, the impatient, or investors with shallow pockets. But Carolina’s proprietors were intimately familiar with colonial administration, trade networks, and the production of crops and commodities for export. They were confident that agricultural staples produced in the humid, subtropical climate of the American southeast would find ready markets elsewhere. The province promised riches enough for proprietors, as well as leading planters who would oversee the colony’s servile workforce.13 Smaller planters—“farmers” in the parlance of most settlements—also stood to benefit, but their path to prosperity would hinge on perseverance and emulation of their social and economic superiors.14

The marriage of interests that ultimately led to a transfer of Barbadian culture to the American mainland was the concurrence of the 1663 Carolina grant with increasing adversity in the West Indies. While Charles II was demonstrating his largesse in England, sugar barons were trying to cope with falling prices, restrictions imposed by the Navigation Acts of 1660 and 1663, soil exhaustion, deforestation, a declining supply of indentured servants, and dangers posed by the fast-growing population of enslaved Africans. Those problems, along with land shortages and high mortality rates, steered disgruntled planters and impoverished former servants toward other shores, most notably England, Jamaica, Virginia, and New England.15 Unlike most English farmers, Barbadian planters already knew what it took to succeed in a hardscrabble colonial setting. They had experience procuring workers, constructing buildings and “works,” clearing fields, planting and harvesting crops for export, managing day to day operations, and using force, when necessary, to increase productivity and maintain control. Thus the Lords Proprietors welcomed and even solicited proposals from Barbadians regarding the establishment of a colony in Carolina.16 The strategies and techniques the latter had perfected were already being replicated elsewhere in the Caribbean; perhaps they would work on the American mainland as well. Even Barbados’s white underclass—those Irish servants “derided by the Negroes, and branded with the Epithite of ‘white slaves’”—were familiar with the cycles and rigors of plantation life.17

In the summer of 1663, a group of Barbadian merchants and planters recruited William Hilton to explore eastern Carolina. His Relation of a Discovery lately made on the Coast of Florida provided the reassurance the eighty-five “Barbadian Adventurers” sought. After the Lords Proprietors made “concessions and agreements” that included self-government, freedom of religion, and generous land grants, the islanders established a colony on the Cape Fear River.18 Despite a promising start, poor relations with neighboring Native Americans and the failure of the proprietors to provide adequate support—an omen of future disappointments—eventually caused the settlers to abandon the colony.19 One positive outcome of the enterprise was the Barbadians’ impression that more suitable areas for settlement lay further south. In his 1666 Relation, Captain Robert Sandford reported that Carolina offered “ample Seats for many thousands of our Nation … in a clime perfectly temperate to make the habitacon pleasant.”20 Opportunities in Carolina seemed boundless when viewed from distant and diminutive Barbados. Moreover, the peace concluded between England and Spain in 1667 seemed to open doors to new colonizing efforts, though territorial claims of the two nations did overlap in the Carolina grant—a minor point among diplomats but not so for colonists who would occupy the contested lands.21

It was at that point that the Lords Proprietors were stirred to action by Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who spearheaded an effort to acquire title to islands in the Caribbean that might be colonized in tandem with Carolina. In addition, the earl persuaded his fellow proprietors to contribute £500 to finance settlement on the mainland.22 Profit was the group’s primary goal, but their funds would also support an expansion of empire and an extension of Protestantism. The colonizing enterprise would enhance England’s trade and provide a bulwark against Spanish and French papists in North America. In Shaftesbury’s view, the Province of Carolina presented settlers with an opportunity for economic and social improvement. But recent experience had shown that colonists could not simply be steered toward America and left to their own devices; they needed a contractual blueprint—one that served their interests as well as those of their landlords and their sovereign. Toward that end, Shaftesbury and John Locke and the other Lords Proprietors collaborated on a founding document—a “Grand Model”—consisting of 120 articles. In theory, it promised political stability, collective security, internal civility, and economic opportunities befitting one’s station in life.

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury after John Greenhill, oil on canvas, based on a work of circa 1672–1673. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina divided the province into counties, each of which contained eight signiories, eight baronies, and twenty-four colonies, each twelve thousand acres in size, spread across four precincts. The plan called for colonists to live and labor in a network of villages or towns located along navigable rivers. In those enclaves, agricultural experimentation and innovation would encourage the production of exotic commodities for export.23 Carolina would thrive on commerce, complementing rather than competing with English agriculture and industry. One-fifth of the land would be “perpetually annexed” to the Lords Proprietors, an equal amount would be reserved for the province’s “hereditary nobility,” and the remaining three-fifths would be assigned to the various colonies so “the balance of the government may be preserved.” By linking authority to land ownership, the Fundamental Constitutions would diffuse power and yet “avoid erecting a numerous democracy.” The document also instituted a hierarchical administrative structure that included a Grand Council, a unicameral parliament, lesser officials, and a complex system of courts.24

While certai...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- One: Barbadian Precedents

- Two: Carolina

- Three: Paradise Lost

- Four: “Dreadfull Visitations”

- Five: Reapers

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index