- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

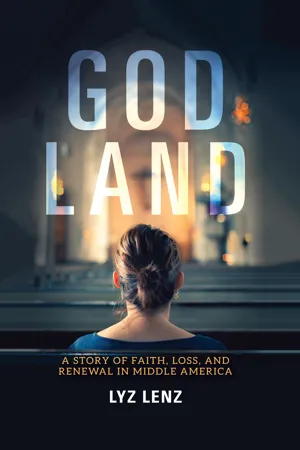

About this book

"Will resonate with any readers interested in understanding American landscapes where white, evangelical Christianity dominates both politics and culture." —

Publishers Weekly

In the wake of the 2016 election, Lyz Lenz watched as her country and her marriage were torn apart by the competing forces of faith and politics. A mother of two, a Christian, and a lifelong resident of middle America, Lenz was bewildered by the pain and loss around her—the empty churches and the broken hearts. What was happening to faith in the heartland?

From drugstores in Sydney, Iowa, to skeet shooting in rural Illinois, to the mega churches of Minneapolis, Lenz set out to discover the changing forces of faith and tradition in God's country. Part journalism, part memoir, God Land is a journey into the heart of a deeply divided America. Lenz visits places of worship across the heartland and speaks to the everyday people who often struggle to keep their churches afloat and to cope in a land of instability. Through a thoughtful interrogation of the effects of faith and religion on our lives, our relationships, and our country, God Land investigates whether our divides can ever be bridged and if America can ever come together.

" God Land, Lyz Lenz's much-anticipated debut book, is a marvel. Not only is it a window into the middle America so many like to stereotype but fail to fully understand in all of its complexity, but it mixes reportage, memoir, and gorgeous prose so seamlessly I wanted to know how she did it." —Sarah Weinman, author of The Real Lolita

In the wake of the 2016 election, Lyz Lenz watched as her country and her marriage were torn apart by the competing forces of faith and politics. A mother of two, a Christian, and a lifelong resident of middle America, Lenz was bewildered by the pain and loss around her—the empty churches and the broken hearts. What was happening to faith in the heartland?

From drugstores in Sydney, Iowa, to skeet shooting in rural Illinois, to the mega churches of Minneapolis, Lenz set out to discover the changing forces of faith and tradition in God's country. Part journalism, part memoir, God Land is a journey into the heart of a deeply divided America. Lenz visits places of worship across the heartland and speaks to the everyday people who often struggle to keep their churches afloat and to cope in a land of instability. Through a thoughtful interrogation of the effects of faith and religion on our lives, our relationships, and our country, God Land investigates whether our divides can ever be bridged and if America can ever come together.

" God Land, Lyz Lenz's much-anticipated debut book, is a marvel. Not only is it a window into the middle America so many like to stereotype but fail to fully understand in all of its complexity, but it mixes reportage, memoir, and gorgeous prose so seamlessly I wanted to know how she did it." —Sarah Weinman, author of The Real Lolita

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access God Land by Lyz Lenz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Social Science Biographies1

DANGEROUS SPECULATION

WHEN I WONDER ABOUT WHERE THE CRACKS IN everything began, I go back to Stonebridge. Stonebridge was a church that my husband and I and six other friends tried to start in Marion, Iowa, in 2010. We were all frustrated with what we saw as faith in America. We were frustrated with faith in our town. And in the beginning, we were united in our grievances. In our estimation, the churches did little for the town. They had loud brassy bands and hip pastors, but no substance. There was no community. And everyone always looked the same. There had to be another way, and so we decided to make something for ourselves.

It’s a very colonizing impulse to look at something—a land, a city, a culture—and instead of seeing what is there, see a barren landscape that needs your new ideas. It’s an American impulse to see a problem and think you can solve it with a little hard work and some bootstraps. It’s a deeply human impulse to look all around you and see a problem but never consider that you might be the actual problem. If we had, for a moment, pondered the logic of any one of our impulses, everything might have turned out differently. But we didn’t. And so, we got into a mess.

The problem we saw that we wanted to solve was this: in our state there were anemic rural churches that lacked vibrancy. And vibrant city churches that lacked depth. We would change all of that. We’d build something small but robust. Something holy and relevant. Something meaningful and practical. Reading over our notes from those meetings feels a lot like asking a twenty-year-old man what he wants in a woman and hearing him say, “I want her to be outgoing but also like a night in. I want someone who likes to have fun but will also cook a three-course meal. A lover and a mother. A simple woman who has class and taste. Who loves to save money but does all the shopping.” In sum, we didn’t know what the hell we wanted. But we thought we did. And at least we knew we didn’t want any of the other places we’d been to.

Since moving to Cedar Rapids in 2005, Dave and I had attended almost twenty churches. One church we went to never invited us into a Bible study. When I asked a pastor or a Sunday school teacher about Wednesday night Bible studies, I was always told to ask someone else, who told me to ask someone else. This went on for five months, until one Sunday the pastor preached a sermon about the importance of small groups and said from the pulpit that all we had to do was ask to be invited. We never went back.

Or there was the church we visited in 2006 that sent three teams of elders to prayer walk around our townhouse. I sent them packing after I opened the door and asked them what they were doing. “Can we speak to your mom?” asked one of the older gentlemen in a suit and tie.

“I am the mom,” I said and slammed the door shut. They left a flyer under the door and walked around our townhouse praying once more, for good measure.

There was the church we visited in 2005, where we heard several sermons about not “jumping ship” when your “church goes bad.” The “bad” was vague and never specified. Needless to say, we did not go back there either.

After three years of searching, Dave and I finally ended up at an Evangelical Free Church. It was there we met the couples we started Stonebridge with and got involved with the youth group. But even then, that church wasn’t an easy fit for us. Or, I should be clear, it wasn’t an easy fit for me. The church was a lot like the Evangelical churches Dave and I had attended as kids—raucous music, a pastor who gave sermons that often included video clips and pop-culture references. There was no liturgy, there were no organs, and most of the people who attended seemed to be our age. Few people drank, no one smoked, and they all loved to discuss the book of Revelation after one too many Mountain Dews at a church party.

While I loved the people there, I didn’t like the church’s theology. The church was and is very conservative; their theology was that of the Evangelical Free Church of America, which doesn’t affirm women or gay people as pastors or elders. Here, strict gender roles were enforced and even seen as freeing. Everybody was white.

As someone who doesn’t like to wear bras on principle, I frequently found myself chafing against the strict orthodox interpretation of the Bible and the long lectures I was often given by male members of the church about how, if I believed women could be pastors, I was questioning the inerrancy of the Bible.

But in those early days of my marriage and my adult life, I thought that these problems were minor squabbles. Something to be hashed out over late nights playing board games and drinking wine—or wine for me, Fresca for the rest of them. It was a privilege, born of my childhood raised in a white Evangelical homeschool subculture in Texas. Until I went to high school at a public school, everyone I knew believed in a literal six-day creation by the hand and voice of God. Everyone believed that being gay was a sin. I was used to being the outsider—the lone voice of dissent. I was comfortable with this role because I wasn’t threatened by it. Not yet, anyway. I wasn’t gay. I wasn’t a person of color. I was a woman, but the gentle grasp of patriarchy hadn’t yet threatened to strangle me, because I hadn’t yet tried to get free. Or perhaps I had, but I was so used to a religion that told me I was wrong and objectionable, it never occurred to me there could be another way.

Faith was also so much more to me than a God I occasionally sang songs to in church or prayed to over meals. Faith had provided the entire fabric of my life. It was the cytoplasm in which I existed—the amniotic fluid that sustained my relationships with my husband and my family. My mother read the Bible to us in the mornings, and my father read it to us before I went to sleep at night. I could not conceive of myself outside of religion.

I often thought about telling Dave or my parents that I didn’t believe in God. That I no longer wanted to go to church. But how could I forsake the inheritance of my childhood? Even now, that deep-soul thump of God and eternal judgment still rises in me when I hear “I’ll Fly Away” or “The Old Rugged Cross.”

Because I could not imagine life outside the womb of my faith, I struggled inside its limitations. I thought there would always be room for me. But the reality was, there was only room for me if I made myself smaller and smaller and smaller, until I disappeared. Or else I’d be pushed out into a bright new horrible, beautiful world, where I would gasp and scream and try to breathe, for once, on my own.

But in those early days, I kicked around, trying to make my place, approaching my disagreements head on. During a membership class at our Evangelical church, the one we’d later leave, I eagerly debated the head pastor, Travis, over whether the Bible supported female ordination. My husband, who agreed with the church’s stances, sat stone-faced as I recited the arguments I’d learned from my Lutheran friends and from reading books such as Ten Lies the Church Tells Women. The pastor gamely debated me but stood strong. “I agree the topic needs more investigation,” was all he would allow. And I took it, that proffered breadcrumb, as a promise to journey together—to listen to one another. I took it as a sign of respect. And that’s all I needed. I didn’t need to be right; I just needed to be treated like someone smart, someone with something to offer besides filling a nursery volunteer spot on Sunday mornings. I needed to be treated like a person.

The promised investigation never came. That offer was just a way of putting me off, shutting me up. A year later, when I asked if we could have a Bible study that opened up the topic, I wasn’t shut down; I was just ignored. I asked the question of the pastor, and he smiled and said, “I’ll think about it.” Nothing else. And every time I brought it up, that’s what I was told. “I’ll think about it.”

Death by a thousand maybes.

It’s a passive-aggressive technique—a denial by silence. There is nothing to fight against. Just resolute lips and an unfocused gaze that refuses to see you, your desperation, humanity, and longing. I’m used to that look. I get it a lot. Or at least, I used to.

I’ve spent my whole life in conservative Evangelical churches. Born the second of eight kids and raised in Texas, I spent my spiritual childhood hearing hour-long sermons in humid brick churches filled with the Holy Spirit and hymns and pastors who sweat through their shirtsleeves proclaiming the second coming of the Lord.

In Sunday school, we looked for signs and revelations of the impending apocalypse: the tentative peace recently brokered in the Middle East, the talk of rebuilding the temple in Jerusalem, the war on religion we were told that Janet Reno was perpetuating with the attacks on Ruby Ridge and Waco. I went to sleep afraid I’d wake up to find my whole family raptured. When I went to the toilet, I prayed to Jesus not to call me up to heaven right then and there with my pants pulled down.

At home, my father taught us that numerology showed Hillary Rodham Clinton’s name worked out to 666. My mother made us read The Hiding Place, and we talked about what we’d do in the End Times when we were persecuted for our faith.

I read Frank Peretti’s books, hiding under the covers, dreaming about the thin veil between the spiritual world and the one where I bit my nails and prayed for Jesus to make me good. I was no good in the churches of my childhood—I was too loud, too demanding, I looked too much like a boy, I asked too many questions.

By the time I was eighteen years old, I’d been in small churches where pastors slept with congregants and in megachurches where youth pastors slept with teens. I’d seen gay women kicked out of the congregations they loved because they wouldn’t apologize for who God created them to be. I’d seen my friend, pregnant at sixteen, asked to stop singing with the worship team, while the boy who was the father still led prayers on Wednesday nights. By the time I finally went to college, I had given up. For four years, I never went to chapel. I still believed in God, but I didn’t believe in church.

After I graduated and married Dave, who’d been raised in the soft Evangelicalism of the upper-middle-class, white, Midwestern suburbs, I was determined that we would find a new church together: one that fit both of us.

We moved to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for his job, and the first thing he did was make a list of all the churches he wanted to visit, without my input. In hindsight, this wasn’t a good sign. But it’s also how he put together our budget, planned vacations, and bought cars. I had a choice—and that choice was to choose from the options on his spreadsheet. And when you are young and in love and used to the patriarchy as a modus operandi, well, you put up with a lot of things without thinking.

Dave and I worked through the list in alphabetical order until we finally settled into the Evangelical Free Church. We weren’t looking for perfection; we just wanted a home. Or, more accurately, I wanted a home. I wanted a place that would accept all of me. Where I wouldn’t be forced to hide my questions and my doubts, swallow my fears and outrage, and get along. Perhaps that’s why, when Pastor Travis told me we’d talk about it later or that he was thinking about my idea of the Bible study examining the woman’s role in the church, I took him at his word.

Compliance is easier than questioning. The appearance of unity is easier than the messy actualities. And I think part of me always understood that if I pushed too hard, I would be cast out of everything I knew. That I’d lose everything. So, I smiled during sermons I hated. I kept silent during Bible studies where people spoke of dinosaurs and humans roaming the earth together before Noah’s flood.

Dave and I put everything into that church. We volunteered with the youth on Wednesday nights, I helped with the coffee and in the nursery every Sunday, and we went on a trip to Israel and on a mission trip to El Salvador. On that mission trip, everything fell apart. It fell apart because I asked to lead the prayer during devotionals one morning. Steven, the pastor leading the group, had frowned and told me that wasn’t my place. I was furious. I had a specific story I wanted to share. One of our local hosts, who was a woman and a pastor, had taken me with her on her visits to the sick people in the village. I’d used my Spanish-English dictionary to talk to a man about how my sisters had been hit by a car, just like he had. How one of my sisters also had a hard time walking. It was a small moment of connection that I wanted to tell everyone about, and I wanted to pray for him.

But Steven was upset because I had been with a female pastor, and he didn’t think it was my place to be leading devotions in our majority-male group. Steven’s approach even angered Dave. When I had told Steven that nothing in the Bible prevented me from talking out loud in a small group, he replied by saying, “It’s there in the Scripture, right here where you are told to submit.”

When Dave and I returned from the trip, we met with Pastor Travis and voiced our concerns. We had heard that other people had similar concerns with this same pastor, and I said as much.

“What? Who?” Travis said.

“You know who,” I said. “They told me they told you.”

“No one told me anything,” he said.

My husband spoke up. “We know people have talked to you about how this man treats people.”

Pastor Travis bowed his head and folded his hands for a moment. When he looked up, he met my husband’s eyes and said, “You are right. I don’t know why I lied, and I apologize to you.”

“Apologize to me,” I said. “You lied to me, not to him.”

“I did apologize to you when I apologized to your husband,” Pastor Travis replied, looking not at me but at Dave. We had been going to that church for five years together and here I was, not even worthy of an apology.

I had trusted Pastor Travis. I had believed that, even though we disagreed, he saw me as a human—smart, worthy of time and consideration. But in that moment, with his resolute lips and gaze focused somewhere over my head, I saw that I wasn’t a whole person to him. I wasn’t even worthy of my own apology. Whatever story I had told myself about mutual respect turned out to be just a lie. That offer to “journey together” was just a coded way of saying, “You’ll eventually grow up and agree with me.” It wasn’t the last time I heard that phrase.

Perhaps during his d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Dangerous Speculation

- 2. The Heart of the Heartland

- 3. Yearning for Better Days

- 4. The Pew and the Pulpit

- 5. The Church of the Air

- 6. Room at the Table

- 7. A Muscular Jesus

- 8. The Asian American Reformed Church of Bigelow, Minnesota

- 9. Bridging the Divide

- 10. A Den of Thieves

- 11. The Violence of Our Faith

- 12. Reclaiming Our Faith

- 13. The Fire Outside

- Notes

- About the Author