![]()

Part 1

Recent Sign Language Laws

![]()

1‘Ah, That’s Not Necessary, You Can Read English Instead’: An Analysis of State Language Policy Concerning Irish Sign Language and Its Effects

John Bosco Conama

Introduction

The Irish Sign Language Act1 (hereafter the ISL Act) was signed into law on 24 December 2017 (Figure 1.4). At the time of writing, it is too early to assess the actual impact of the Act on current national language policies. In light of this, the chapter focuses on how ISL is legislatively managed in the shadow of the dominant language English and a lesser used language, Irish (Gaeilge). Irish and Irish Sign Language (ISL) bear no direct relation to each other, though the common public often wonders if they are related or even the same language. Irish is constitutionally recognised as the national and first language of Ireland. In terms of state support, it holds a far advanced position compared to that of ISL. Yet within the jurisdiction of the Republic of Ireland, both Irish and ISL are de facto subordinate to English.

While English and Irish are constitutionally recognised languages in Ireland, English, by default, is regarded as the standard, dominant language that requires no specific legislation (Darmody & Daly, 2015). Yet Gaeilgeorí (Irish speakers) found it necessary to seek specific legislation to bolster their linguistic rights supporting access to public services in their chosen language. This support materialised in the form of the Official Languages Act 2003. Despite this Act and the national cultural affinity for Irish, Gaeilgeorí continue to express dissatisfaction with regard to how public officials treat them linguistically (Nic Shuibhne, 2001; Watson, 2016).

The public often perceives official language policy in Ireland as having a dominant focus on the revival and maintenance of Irish (Atkinson & Kelly-Holmes, 2016; Conama, 2010), and political attempts to enhance the status of Irish are often met with a general antipathy (Darmody & Daly, 2015). Despite the official image of Ireland as a bilingual nation, and even an emerging popularised image of Ireland as a multilingual nation, the reality is that monolingualism remains solid on the ground (Mahon, 2017). Public servants do display monolingual behaviours and attitudes when dealing with language issues (Rose & Conama, 2017; Ni Drisceoil, 2016; Walsh, 2012). In contrast to this, during the ISL recognition campaign, members of the public often expressed disbelief when learning ISL had not yet been bestowed official status. While it is difficult to pinpoint the reasons to explain this surprising contrast, it is possible that the experience of learning Irish in schools has left a negative legacy for many people (Devitt et al., 2018), while ISL is associated with a positive emotional feeling.

The campaign for ISL recognition demanded the recognition of ISL as the third official language of Ireland (see Figure 1.1), and also referred to ISL as Ireland’s second indigenous language, alongside Gaeilge. Speakers of other (non-indigenous) languages such as Polish or Chinese can avail of online public services such as state social security information2 and employment rights, to a limited extent. However, public services are not legally obliged to provide such access since there is no enforcing legislation to demand this. Public officials often see requests of ISL users to extend linguistic access to ISL as irrational (Conama, 2010). Indeed, public services often resort to the ‘solution’ of making English text available for Deaf3 ISL users, rather than producing video translations in ISL (Conama, 2010).

Figure 1.1 Campaign boards from an ISL rally in Dublin, September 2015

Photo credit: Maartje De Meulder.

Campaigners for state recognition of ISL (led by the Irish Deaf Society with the author as its main representative) have successfully drawn upon such differing treatments, resulting in the successful passage of the Bill seeking the recognition of ISL.

In Ireland, in order to get a parliamentary bill passed, if it is proposed by the Seanad (the Upper House), it has to undertake 10 stages – five stages in each House (upper and lower). At each stage, a bill is minutely scrutinised and debated before the final vote, giving politicians and government officials the opportunity to propose amendments and mould the legislation. The ISL Bill went through the five stages of legislative recognition in both houses of the Oireachtas (Irish Parliament), culminating in the signing of the legislation by the President of Ireland.

Campaign to have ISL Recognised

For brevity and convenience, the following sections distinguish between the legislative process and the campaign; however, both were deeply interwoven.

In looking back, there is no specific watershed or historical milestone that can be regarded as the starting point for the campaign for ISL recognition, but an incremental path can be observed from the establishment of the Irish Deaf Society, the national Deaf-led organisation, in 1981, and its development of international connections to the World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) and the European Union of the Deaf (EUD). The international aspects of the campaign include the WFD’s resolution in 1991 calling on national associations to pursue the official recognition of sign languages and the successful resolution on sign languages brought forward by an Irish Member of the European Parliament in 1988. Given Ireland’s vicinity to the UK, there is regular exposure to the UK media, and the Deaf community in Ireland have regularly watched stories of the campaigns for signed language rights in the UK. Paralleling this exposure there has been an increase in the number of Deaf people entering universities and who were beginning to adopt a critical perspective on (life) issues of language identity as highlighted by O’Connell (2017) and Conama (2010).

The rationale behind the campaign for the ISL Act can be linked to an international desire to protect and promote signed languages, ensuring such languages can be enjoyed by future generations. This is not unique to Ireland; De Meulder (2015) and the Council of Europe (2003) have identified the preservation, protection and promotion of signed languages as the most important reasons behind campaigns for the legal recognition of signed languages. Additionally, the transmission of signed languages and their aligned cultures almost always takes place on a ‘horizontal’ basis4 (Hill, 2015: 197), which entails a significant risk to the survival and sustainability of ISL, and is one of the factors that has necessitated a campaign for the official recognition of ISL. The steady decline of the number of Deaf children in the residential schools and the wide dispersal of deaf children in mainstream education inevitably erodes the ‘natural’ base for producing and sustaining the number of signers.

McKee and Manning (2015) and Johnston (2006) have outlined the potential threats and risks to the traditional basis of signed languages in other countries such as New Zealand and Australia. It is not unreasonable to envisage a similar situation for ISL (for a discussion see Leeson & Saeed, 2012). Following on from this analysis, brief comparative parallels can be seen between the desire to have ISL and Irish properly resourced to ensure their sustainability.

Campaign strategies

From the initial drafting of the ISL Bill in 2009, the Irish Deaf Society (IDS) followed two main strategies. The first one was collaboration with Senator Mark Daly of Fianna Fáil (a centrist and nationalist political party) (Conama, forthcoming). For the upper house of the Irish parliament in certain categories candidates have to seek nominations from the registered civil society groups in order to stand for the Seanad election. Senator Daly sought the IDS’ nomination and was successful, and was committed to raise any concern the IDS wanted to highlight. The second one was the set-up of the cross-community group within the Irish Deaf community, facilitated by the IDS. This group included various national organisations ranging from Deaf youth to interpreters, and was created with the purpose of presenting a strong, cohesive, community response to the issue of recognition and deflect any potential criticism that the community was not united on this topic. This group advised the IDS representatives collaborating with Senator Daly.

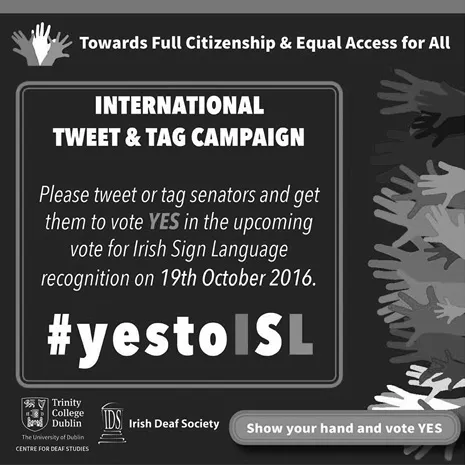

The IDS also availed use of social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to keep the community informed about the campaign’s developments. On Twitter, the campaign used the hashtag #yestoISL (see Figure 1.2). The ‘Irish Sign Language Recognition Campaign’ Facebook page has over 3,000 followers, and offered members of the community an opportunity to query and debate issues in relation to the campaign. In addition, this proved to be a useful information outlet encouraging members to take active roles in the campaign at a local level (see Lawson et al., Chapter 4, this volume, for how Facebook has been used in the campaign for the Scottish BSL Act).

Figure 1.2 #yestoISL tweet and tag campaign

Credit: Haaris Sheikh.

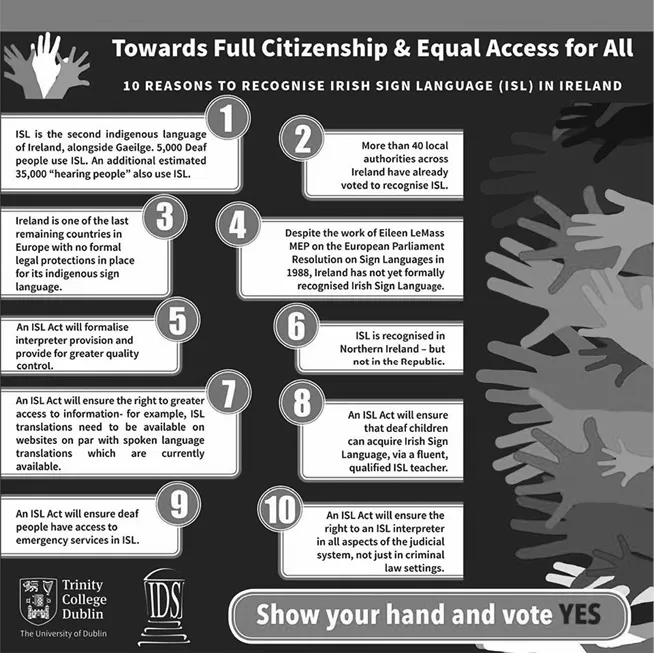

The campaigners also disseminated a leaflet with 10 reasons to recognise ISL (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Ten reasons to recognise ISL

Credit: Haaris Sheikh.

Figure 1.4 (From left to right) Senator Mark Daly, Eddie Richmond (IDS CEO), Brendan Lennon (Deaf Hear), Fr Gerard Tyrell (chaplain), Lianne Quigley (IDS Chair) and Dr John Bosco Conama

Paralleling the initial legislative work on the ISL Bill, the IDS launched a separate campaign asking local authorities to pass a standard motion calling on the government to recognise ISL. The campaign not only engaged with local governments, but also with local media. In 2012, Monaghan County Council became the first local authority to pass such a motion after one of its councillors visited an ISL photography exhibition at a local gallery and decided to propose a motion. When reflecting upon this motion, the IDS realised the huge potential impact that could take place at a local level. The campaign continued, reaching completion with Waterford County Council becoming the 48th and final local authority to pass the motion. The level of coverage in local media appeared to show the success of putting forward this motion at a local level.

Development of the Bill

Originally, Senator Daly (a member of the parliamentary opposition) proposed that a government representative should take responsibility for tabling the Bill (Senator Mark Daly, pers. comm., 2011). However, attempts to get the government to table the Bill and initiate the process failed, though no clear reason was given for this reluctance. Separately, and paradoxically, given the reticence to take responsibility for the Bill, government Senator Cáit Keane, who had been working on sign language issues previously,5 proposed a motion calling on the respective governments of each nation in the British Isles to recognise their signed languages. This motion was passed in Glasgow in October 2012 (British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly, 2012).

Senator Daly engaged a legislative draftsman to draw up the Bill, in consultation with IDS representatives. Their initial work entailed examining several pieces of legislation on signed languages and drew chiefly upon those from...