eBook - ePub

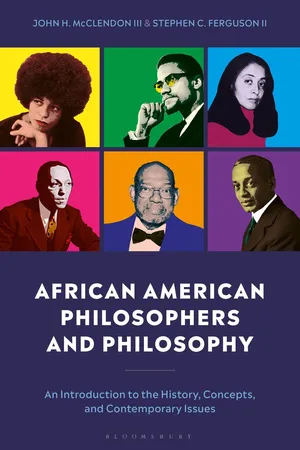

African American Philosophers and Philosophy

An Introduction to the History, Concepts, and Contemporary Issues

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

African American Philosophers and Philosophy

An Introduction to the History, Concepts, and Contemporary Issues

About this book

This book presents the first introduction to African American academic philosophers, exploring their concepts and ideas and revealing the critical part they have played in the formation of philosophy in the USA.

The book begins with the early years of educational attainment by African American philosophers in the 1860s. To demonstrate the impact of their philosophical work on general problems in the discipline, chapters are broken down into four major areas of study: Axiology, Social Science, Philosophy of Religion and Philosophy of Science. Providing personal narratives on individual philosophers and examining the work of figures such as H. T. Johnson, William D. Johnson, Joyce Mitchell Cooke, Adrian Piper, William R. Jones, Roy D. Morrison, Eugene C. Holmes, and William A. Banner, the book challenges the myth that philosophy is exclusively a white academic discipline. Packed with examples of struggles and triumphs, this engaging introduction is a much-needed approach to studying philosophy today.

The book begins with the early years of educational attainment by African American philosophers in the 1860s. To demonstrate the impact of their philosophical work on general problems in the discipline, chapters are broken down into four major areas of study: Axiology, Social Science, Philosophy of Religion and Philosophy of Science. Providing personal narratives on individual philosophers and examining the work of figures such as H. T. Johnson, William D. Johnson, Joyce Mitchell Cooke, Adrian Piper, William R. Jones, Roy D. Morrison, Eugene C. Holmes, and William A. Banner, the book challenges the myth that philosophy is exclusively a white academic discipline. Packed with examples of struggles and triumphs, this engaging introduction is a much-needed approach to studying philosophy today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access African American Philosophers and Philosophy by Stephen Ferguson II,John McClendon III in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Through the Back Door:

The Problem of History and the African American Philosopher/Philosophy

Chapter Summary

Initially we examine the historical formation of African American philosophy from 1865 to now. While there is a tendency to see philosophers and philosophical questions as outside the boundaries of history, we demonstrate that African American philosophy is a product of history. Moreover, we discuss the philosophical problems attached to defining African American philosophy. (54)

The French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser provocatively says that philosophy has no history.1 Althusser’s somewhat cryptic statement brings to our attention that philosophy as a discipline often ignores the historical and social conditions for the emergence of philosophers and philosophical doctrines and trends. Accordingly, the popular image of philosophy reflects something so abstract that its subject matter stands apart from the social circumstances of working people and the dynamic events of everyday life. On this point, African American philosopher Henry Theodore Johnson remarks the following:

There is a general disposition on the part of the “common herd” (as Schopenhauer bluntly characterizes the unreflecting multitude) to regard all philosophy as so much moonshine in the abstract. To the conception of such, that is philosophy whatever they cannot comprehend, which is intelligible to no one and devoid of value as a human commodity to all men. Indeed, philosophy seems to have a bad name everywhere among the ordinary populace.2

Given the social division of labor where the separation of mental and manual labor persists, what often results is the viewpoint that philosophical reflection appears as the solitary dominion of those in the ranks above the toiling masses. Plato and Aristotle prominently held this view.

Concurrently, from the standpoint of certain philosophers, there persists the opinion that the love of wisdom (Philo—Sophia) exceeds the bounds of history as a timeless search for truth. It seems we are faced with a nagging dilemma. On the one hand, we have philosophical inquiry presented as a timeless search for truth, which transcends the historicized—material—world. On the other hand, we must confront the fact that philosophers are material (social) beings and thus are in—and of—the historically situated world of social reality. As Karl Marx insightfully notes,

Philosophers do not spring up like mushrooms out of the ground; they are products of their time, of their nation, whose most subtle, valuable and invisible juices flow in the ideas of philosophy. The same spirit that constructs railways with the hands of workers, constructs philosophical systems in the brains of philosophers. Philosophy does not exist outside the world, any more than the brain exists outside man.3

If philosophy does not exist outside the world, then it cannot exist outside of history. Accordingly, the African American philosopher is very much the product of history. The history of African American philosophy is a complex and intricate story of persons, ideas, institutions, and sociohistorical events. The present work is only the beginning of the story; it is not the end. We contend that the future of African American philosophy is to be found in the judicious examination of its past.

Prior to Leonard Harris publishing his anthology Philosophy Born of Struggle in 1983, Percy E. Johnston’s Afro-American Philosophies: Selected Readings from Jupiter Hammon to Eugene C. Holmes, published in 1970, was the only text devoted to the writings of African American philosophers and the philosophy of the Black experience. Presently, we are witnessing the production of an array of books attentive to African American philosophers. And we have seen a proliferation of anthologies devoted to African American philosophy and/or the philosophy of the Black experience. One of the most significant contributions is George Yancy’s African-American Philosophers: Seventeen Conversations (1998), a collection of interviews from a wide range of African American philosophers.4 Despite the array of available works, the professional field of philosophy—not to mention the general reading public—still knows very little about the history of Black philosophers, both professional and nonprofessional alike. Unquestionably, we need more solid—well researched—texts on this subject with a wide distribution inclusive of the scholarly and general reading audiences.

Solid texts in the history of African American philosophy can only emerge when certain core questions are meaningfully and adequately addressed as the focus of theory and method, particularly respecting the historical record. Now let us systematically interrogate the subject matter of the history of African American philosophy. In that regard, we submit the following questions as a brief sampling of possible interrogations. The first set of questions is empirical in nature and the second is more conceptual in tone.

Our first set of questions includes the following: Who are the African American thinkers that have grappled with philosophical questions and problems over the course of the history of African American philosophy? What type of training/education did they receive? What were the venues (institutional setting) available for their work? Were such outlets academic or nonacademic in makeup or did both come into play? What was the relationship between teaching and research for the earlier generations of African American philosophers? What audience did they seek to address? And what means were at their disposal for reaching an audience? What subfields in philosophy did they explore and what schools of thought captured their allegiance? It should be most apparent that the above questions require empirical resear ch.

Our second set comprises the following: Does philosophical theory demand that the history of philosophy posed perennial questions—such as the mind/body problem—of which we witness changes only in form, while what remains as consistently true is an essential content that lasts over time?5 Is the historical method a matter of knowing how to demarcate the past from the present via some method of periodization? How does one weigh the philosophical merit of ideas or issues in philosophy’s history from more general notions concerning intellectual history in the broader nonphilosophical sense of the term—such as the history of ideas? In other words, what are accurately considered philosophical questions, issues, and problems? Finally, do we need the past as the primary yardstick for measuring current levels of philosophical attainment?

On the progress of African American philosophy

Can we see progress—as we discover with scientific inquiry—over the course of the history of philosophy? If there is some kind of progressive development with philosophical thought, then indisputably philosophy has its own substantive history. Of course, this proposition about philosophy’s substantive history divorces us from the idea that philosophy has no history. Perhaps with this thesis—philosophy has no history—the most telling implication entails purging any progressive development from within philosophical thought. From early on, African American philosophers wrestle with the question, namely “what does it mean to talk about progress in Black life?” wherein life is experienced within the existential circumstances of hegemonic racial oppression and class exploitation. Such conditions are indicators for what philosopher Henry T. Johnson fittingly coined as The Black Man’s Burden.6

In the nineteenth ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Biographical Information on Selected African American Philosophers

- Introduction: Footnotes to History: On the Recovery of African American Philosophers and Reconstruction of African American Philosophy

- 1 Through the Back Door: The Problem of History and the African American Philosopher/Philosophy

- 2 The Problem of Philosophy: Metaphilosophical Considerations

- 3 The Search for Values: Axiology in Ebony

- 4 Philosophy of Science: African American Deliberations

- 5 Mapping the Disciplinary Contours of the Philosophy of Religion: Reason, Faith, and African American Religious Culture

- Glossary of Key Terms

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright