![]()

1

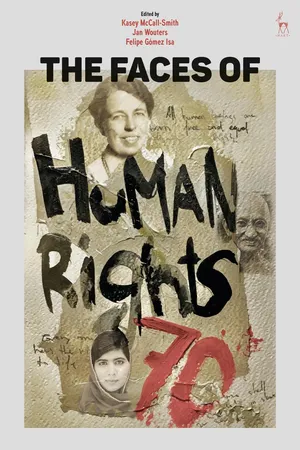

The Faces of Human Rights – An Introduction

KASEY MCCALL-SMITH, JAN WOUTERS AND FELIPE GÓMEZ ISA

I.70 Years of the Universal Declaration: A Time for Reflection

In 2018, when the seventieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was celebrated, many events and publications examined its relevance in the contemporary human rights agenda. The Faces of Human Rights was conceived both as a celebration of the UDHR and a tribute to those individuals who laid the groundwork for that document and, more generally, developed our current conceptions of human rights through their various distinguished contributions to the field: as academics, civil servants, civil society activists, judges, lawmakers, philosophers, politicians, and so on. The inspiration for the project was born in a meeting of the Association of Human Rights Institutes (AHRI) executive committee in Brussels in February 2018 and the contributors are drawn predominantly from the wealth of human rights academics across the AHRI network.

In the past 70 years, the human rights defined by the UDHR have been entrenched in the understanding of every state on the globe. They were reinforced and made legally tangible through the elaboration, adoption and ratification of the twin covenants, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The UDHR further served as the basis for a range of specialised international and regional human rights agreements. Each of these international agreements is underpinned by the core principle set out in Article 1 of the UDHR: ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood’. Irrespective of gender, race, ethnicity, nationality or personal preferences, each and every individual on this earth is entitled to that most basic principle without distinction. Through its 30 articles, the UDHR sets out the protections to which all individuals are entitled, including: the right to life, liberty and security of person; freedom from slavery; freedom from torture and arbitrary arrest; the right to a nationality; the right to free movement and asylum from persecution; the right to thought, conscience and religion; the right to work in decent conditions without discrimination; to participate in public life, to name but a few. And while states’ commitments to fulfilling these obligations have ebbed and flowed depending on the political and social landscape in and around their borders, the UDHR has been translated into over 500 languages and embedded in the promise of a better future for our children.

But that language and the fundamental value of human dignity are currently under major threat. The very states that rode the coat-tails of human rights toward democracy are increasingly ignoring or outright rejecting the fundamental precept that all human beings are born free and equal. Some leaders of the ‘free world’ eschew the idea of a collective international community based on the rule of law with the protection of individual citizens at the heart. In the aftermath of conflicts and mass migration, nationalist populist movements are once again in vogue and challenging even the most basic of human rights canons. The lack of moral leadership in formerly staunch human rights promoting states has given more space to oppression by various autocratic and non-democratic regimes. In some ways, this book responds to the threats to peace, the fear-mongering, the ‘othering’ that seem so trendy in political rhetoric as a means of degrading the basic dignity of humankind. Through these pages, we seek to recall the reasons why human rights are so essential to the post-Second World War peace and how the flame that is human dignity continues to burn and move individuals to act in its pursuit. It is through this reflection that we recall that behind the UDHR, the many additional human rights treaties, the bureaucracy, the struggle and the heartbreak are the people who have fought to maintain the inherent self-worth and freedoms of every human, and continue to do so, one cause, one speech, one article, one conversation, one kind word at a time.

Commencing a project that will freeze a list of individuals key to the development of international human rights at a single moment in time is daunting to say the least. Selecting the ‘faces’ is an exercise with many challenges, not the least of which includes the methodology for developing the list. Depending on one’s education, career and field of travel in human rights, the spectrum of individuals who have impacted their development have done so in many ways and, much like beauty, human rights impact is often in the eye of the beholder. To pursue a complete compendium of human rights influences would be an impossible task, not least due to the fact that new voices are emerging daily and the thread of influence from the voices of the past are continually unearthed. Even among the editors we shared different priority lists. But as the terms of human rights were forged in a spirit of dialogue and consensus, so, too, were the individuals featured in this volume. In our view, the individuals celebrated here reflect a multidimensional perspective to understanding human rights at this point in time. These faces of human rights not only shed light on the birth of foundational human rights principles but speak also to the development of both measured and reactionary responses to inequality and oppression.

In developing our list of ‘faces’, we considered the chronology of human rights development, and took as our starting point the fifteenth century, when European nations were expanding across the globe. These great conquests reaped havoc across the local peoples and in the midst of this brutality, notions of formalised equality in law and policy came through. The notions were often shaped by religious theory and, in turn, the law of nature, which fuelled proponents of political, social and gender equality featured here through the Enlightenment and beyond. All of these primordial inklings of human dignity ultimately found their stronghold in a universal language developed through the UDHR. Thus those who shaped both the development of the UDHR and further international agreements were essential to the selection. Our criteria for selection also sought to reflect the many major struggles that played out in the lead up to or immediately following the adoption of the UDHR in addition to the two World Wars, such as the civil rights movement in the US, the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa and the massive movements disenfranchising indigenous peoples across the globe. The selection also sought to present a regional balance as well as a broad range of different areas of advocacy in a volume that is necessarily limited. Thus women’s rights, indigenous peoples’ rights, LGBTQI rights and disabilities rights activists are featured and, where possible, we have drawn from as varied a pool of locations as research permitted.

Just as human rights do not exist in a vacuum and must be understood as ever-evolving, neither could a volume designed to pay tribute to human rights advocates be complete without a list of contributors that is equally diverse. The authors of these chapters are drawn from across several social science disciplines and are each pursuing their own intrepid hopes for human rights at different stages in careers, from PhD students to seasoned veterans of the UN system. Many of the authors could just have easily been one of the individuals written about in these pages, and will, no doubt, be featured in future projects such as this. Thus, in many ways, the selection of authors was a task on par with the selection of featured individuals.

The book is divided into five parts and, generally, each of the chapters presents a brief biographic history of the individual, their career and contribution to human rights and the author’s personal conclusions on the individual’s legacy in the field of human rights. In this vein, many of the more established contributors have included personal reflections or accounts of their relationships with the individuals they chose to celebrate. In particular, the final chapter written by Manfred Nowak about Theo van Boven is a testament to the way in which those who work in human rights are constantly grooming the next generation to carry the torch of human rights. In the development of these pages, what also became apparent was the mutuality of support, chance encounters, and unity of purpose across the pages. In many instances, the challenges faced by human rights defenders today are sobering in light of the struggles by those featured here, and in that way we must acknowledge the shortcomings of democracy and its failure to deliver well-rehearsed promises made on the back of these struggles.

II.Laying the Foundation for Human Rights through the Law of Nature and the Prism of Equality

The earliest portraits presented in this volume speak to the relationship between the law of nature and religion and how the principles derived therefrom shaped the philosophy and actions of the earliest proponents of human rights. Ignacio de la Rasilla recounts how Bartolomé de las Casas fought tirelessly as a humanitarian political adviser and religious figure to promote the livelihoods of the Amerindians throughout the Spanish conquest of the Americas. Through his defence of innate humanity, based upon natural law, he persisted in opposing evangelisation by gunpoint and sword and served as a precursor to Enlightenment philosophers. Over a century later, John Locke espoused individual freedoms and religious secularisation at the ‘dawn of the modern world’, as recounted by Cristina de la Cruz-Ayuso. His responses to specific situations, like his successors in the quest for protection of individual freedoms, shaped the man and the philosophy that led to him serving as a constant focal point in natural law discourse, and is reflected in the first article of the UDHR ‘that all human beings are born free and equal’. His social contract theory was underpinned by the idea that individual freedom is an essential element of a civil society. He urged tolerance of religion and human knowledge, a message that echoes today, as explored later in the volume.

Close on the heels of Locke are two historic figures who set the stage for contemporary gender and social equality platforms. Teresa Pizarro Beleza and Helena Pereira de Melo introduce readers to Olympe de Gouges. Committed to her personal convictions and crusade for autonomy to her death, de Gouges’ Declaration of the Rights of Women implores readers to recall that the contemporary challenges of hatred, bigotry and sexism of today are the same as those faced by de Gouges and her eighteenth century contemporaries. The contradictory life and writings of Mary Wollstonecraft are unpacked by Dolores Morondo Taramundi. Embattled by her own personal demons and the turbulent politics of the late eighteenth century Enlightenment, Wollstonecraft used the power of her pen to elucidate the case for universal justice comprised of gender equality and improved social conditions for the peasantry.

Henry Dunant, the father of humanitarian law, is brought to life by Joana Abrisketa Uriarte, who sets out how Dunant’s personal experience of helping victims of war propelled him into a lifelong campaign for international consensus on rules enabling the aid and enduring dignity of civilians and wounded combatants, in what ultimately developed into the International Committee of the Red Cross and was codified in the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions. In the final chapter of part I, George Ulrich chronicles the principled, peaceful protest of a man emphatic that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights; Mahatma Gandhi leveraged personal pleasure and comfort in the pursuit of social justice through the Satyagraha ideal of non-violent resistance. In the end, his non-Western values underpinned the ethos of the UDHR. As Ulrich observes:

[i]n this respect his message to posterity can be seen as a baton – or perhaps better, an unpolished gem – handed over to the Commission on Human Rights, which at the very moment of his untimely death in January 1948 was engaged in drafting the UDHR.

III.In the Shadow of War: Developing Universal Human Rights

Part II shifts to the mid-twentieth century and the drafting of the UDHR. It begins with Hersch Lauterpacht and his vision of universal dignity and commitment to ensuring recognition of crimes against humanity. Eva Maria Lassen paints a portrait of his long-term contribution to human rights and the rule of international law in the face of personal tragedy. In tandem with Lauterpacht’s work, Raphael Lemkin and his obsession with evidencing the horrors of the German extermination of millions of Jews, Roma and other minority groups is presented by Adam Redzik. In his quest, Lemkin pressed for recognition of genocide, a new term of his creation, in the Nuremburg prosecutions and its prohibition, concretised in the Genocide Convention.

The final chapters in part II deliver a rich insight into the people and process of developing the UDHR. An intimate portrait of the most well-known face in the drive to agree the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Eleanor Roosevelt, is revealed by Anya Luscombe and Barbara Oomen. Her personal dignity, assiduity and respect for all humans ensured the realisation of this first universal human rights undertaking, which capped a life spent subtly pushing forward an agenda for equality across the globe, in the US and in ‘the small places close to home’. Next, René Cassin is depicted by Jan Wouters as a man for all seasons: he saw himself as a foot soldier for human rights and contributed in the most diverse capacities to this cause. From his work on war victims and veterans after the first World War to his tireless efforts at the UN (including his role in the development of the UDHR), the European Court of Human Rights and in France for human rights and human dignity, Cassin remains a source of inspiration for generations to come. A reflection on the immense contribution made by John Peter Humphrey as the author of the first draft of the UDHR closes out part II. William Schabas presents how the Canadian life-long civil servant is often left out of the credit rounds when the drafting of the UDHR is celebrated. However, historical documents from his time with the UN Secretariat, as well as his own personal account, point to the crucial role he played in working with Roosevelt, Cassin and others to develop the text that serves as the bedrock document for all human rights.

IV.The Fight against Discrimination in the Places Close to Home

In the post-UDHR adoption era, the difficulty in ensuring human dignity and universal equality quickly became apparent. In particular, minority groups across the globe suffered a range of legal and social injustices, which cut to the core of what it means to be a member of the ‘human’ race. Across the United States, South Africa, Australia, South America and Asia, daily manifestations of discrimination and predatory suppression were the norm. Part III examines a number of the individuals who stood up to engrained, everyday discrimination and celebrates those who continue to do so.

Rosa Parks was not just a woman who was hassled on a bus at the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s southern US. Kasey McCall-Smith charts Parks’ upbringing and life as a determined, considerate and well-trained activist who found herself cast as a leading face in a movement for equality that would occupy her until her last breath. But the alchemy behind the Civil Rights Movement was ultimately crafted by Martin Luther King, Jr, who found himself shoulder-to-shoulder with Rosa Parks following her arrest. Vivek Bhatt weaves the story of King and how he was catapulted into history through his natural, cosmopolitan leadership and dedication to a theology and philosophy of brotherly love that demanded – at all costs – peaceful protest against the habitual and often brutal racial discrimination in the US.

From the US part III then circles the globe surveying the many struggles against discrimination. Narnia Bohler-Muller recounts the parallel struggles of Nelson Mandela against Apartheid in South Africa. Against a long history of colonialism and white oppressions, Mandela never strayed from a message of love for his fellow man, regardless of skin colour. From the horn of Africa to Australia and another hotbed of discrimination, Michelle Burgis-Kasthala charts the gentle activism of Faith Bandler in the first of four chapters examining indigenous peoples’ fight for equality and legal recognition. She describes Bandler’s pursuit to construct a political and legal system acknowledging the dignity of the indigenous peoples of Australia and other minorities enslaved there because it was what ‘we all should be doing’.

Moving to the southern Americas, the next chapter by Elisabeth Salmón details the heart-wrenching efforts of Angélica Mendoza de Ascarza (Mamá Angélica) in her campaign to discover the fate of her son, and the family members of many of her fellow Quechuan who suffered the programme of enforced disappearances by the Peruvian government during the tumultuous conflict that overshadowed the last quarter of the twentieth century. Her simple defiance of maintaining a curtain of ignorance for the victims of these atrocities made her a legend among the disenfranchised and oppressed of Peru. Another face of the Americas is the Guatemalan indigenous rights crusader Rigoberta Menchú Tum, revealed by Felipe Gómez Isa. As an indigenous Mayan, Menchú’s family suffered brutal repression under the Guatemalan regime, with her family members kidnapped, tortured and killed. Following her exile to Mexico, she began denouncing the brutal regime on an international stage and was ultimately awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. To this day she continues her campaign for legal equality for her people.

Skipping back across the Pacific to Southeast Asia, Davinia Gómez-Sánchez details the work of Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, an indigenous Igorot Filippino who played a crucial role in the development of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. So loudly has her voice resonated on the issues of injustice that the current Philippines government has declared her a ‘terrorist’ in an attempt to deflect the criticism she has tirelessly raised against its departures from the rule of law in countless international forums. We end in Pakistan, with a personal tribute to Asma Jilani Jahangir by Mikel Mancisidor following her untimely death in early 2018. In the same vein as those who struggled against oppression based on race or ethnicity, Jahangir dedicated her life to the ideals of democracy by taking a stand against the worst forms of injustice in her home country, including outlandish penalties for blasphemy and victims of rape, one case at a time, but also as a very vocal international activist figure as the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions.

V.Navigating the Politics of International Activism

Essential to developing the international framework of human rights protection on the back of many global struggles are the human rights activists and defenders who sought to shine a light and press for change through engaging in national or global politics and the international human rights system. Part IV opens with the coming of age account of Sean MacBride. Dimitrios Kagiaros...