![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Science of History

History is philosophy from examples, wrote the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus, in the first century BC.

By ‘philosophy’ Dionysius meant politics, sociology, economics and psychology, and by ‘History’ he meant the corpus of historical writing or historiography. So in addition to the uses of History set out below, one of those is as the record of a global psychology laboratory. If it is true that the mainspring of History is human agency (cf: H.T. Wright 2007), then it follows that its substrate is human psychology, underlying which is the evolutionary inheritance we call instinct. This is scarcely surprising as neuroscience now shows that the conscious functioning of the brain is the least part of its activity.

“Young children, whose intentions and sympathies are not merely ‘constructed’ by us, show that our own language and cognitions are more products of a natural organismic process than our politicians, judges, theologians and philosophers, and many of our scientists, pretend to believe” (Trevarthen 2006: 240).

Building on Dionysius, I will begin by offering my own definition of history: History is about understanding how we came to be where we are now, through the study of processes, people and events in the past.

Understanding History is both cognitively satisfying (situating ourselves) and instrumentally useful (‘learning from history’); both good to know and useful to know. Its study helps us understand how societies are constituted and how they change as a consequence of human actions (culture, technology, warfare and politics) in the context of underlying forces (geographic, ecological and economic). Science consists in demonstrating mechanism; social science similarly consists in laying out chains of cause and effect (which is what mechanisms or systems are). History does not stop or ‘leave you alone’ because you are ignorant of its processes. Ignorance just means that you are swept along like a stick in a river. If we substitute the phrase ‘flow of events’ for the term ‘history’, everyone knows this is true. It’s what we’ve done that makes us who we are, as individuals and as societies.

A: Politics and Ideology

The state is a dominant organization backed by force: physical, economic and ideological. But all states are different, even now, even in ‘united’ Europe. They were even more diverse when they first emerged. Mesopotamia gave rise to the earliest cities and to the city-state, derived from large business-like households. Those households were organized around the temples as a community resource and the temples became the nuclei of cities in Sumer. Egypt produced a large territorial state from chiefdoms dominating villages. In China, which generated no city-states, the territorial state (‘village state’) was produced by clans dominated by aristocrats, with other members pushed down to the condition of subjects. “Individual choice disappears when a person has a duty to be a member of a group, or, to say it the other way around, when a group has the right to claim him as a member” (Goodenough 1970: 59).

The state arose in the Andes on a similar basis, that of the descent group. In north-west India, around the Indus, an extensive, populous and complex society existed for half a millennium without state domination. Contrasting the social structures of the two large early territorial states, Baines and Lacovara (2002: 27) observe that “Egyptian societal organization was ‘political’ rather than kin-centred. ... Egypt did not have extended lineage structures; where cults of lineage ancestors are an essential moral focus that coexists with central values, as in China, there is an intricate nesting of social groups and ideologies”.

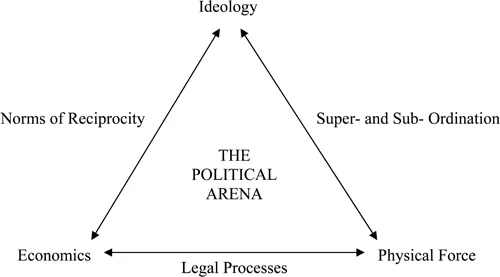

Politics are the traffic between economic power, physical force and ideology. Politics affect all human activity; at home, in the workplace, in the educational institution, at social gatherings and, of course, in the state. Wherever there are humans there is politics. Politics is an arena of contest between the three socially crucial resources already mentioned – Ideology, Economy and Physical Force (i.e. violence and the threat of violence) – that, starting in 1984, I have represented as a triangle, the sides of which consist of specific social relations (Figure 1.1).

The system of contest-exchanges by no means applies only to public or state-level activities, but operates at domestic, village, clan; every level, from the hippiest most egalitarian commune to the line managements of big (or small) business. We personally and daily encounter the politics of the bedroom, of the household, of the boardroom, the common-room and so forth; the social nexus is a political one. Indeed human brain-size, and language itself, evolved in response to the complexities of living in large social groups (Dunbar 1993: 681), having to deal continuously with enemies and allies, mates and rivals, both within one’s own group and in those surrounding. Originally dyadic grooming and then language served to form a network of ‘strategic friendships’ where “These primary networks function as coalitions whose primary purpose is to buffer their members against harassment by other members of the group. The larger the group, the more harassment and stress an individual faces the more important those coalitions are” (Dunbar 1993: 683). Such dealings constitute politics, and for just such situationally dynamic reasons Primates, (Prosimian and Anthropoid) have also evolved politics (Byrne 1995; Dunbar 1988, 1993). Coalitions are, of course, combinations of self-interest; a shared fear or goal is what the participants have in common. The problem with combinations is that defection is easy so soon as one or several members find that their interests are best served elsewhere. This is where ideology can serve a key purpose in convincing members that they share more than just a narrow and expedient self-interest, but rather that some higher, broader or deeper purpose is being served, thus making the attachment stronger by making the appeal emotional. As societies are essentially coalitions, or more accurately coalitions of coalitions, ideologies are a key means of holding them together. The other is the existence of the state, specifically of its apparatuses, one of which, for the reason just given, is bound to specialize in ideology. The functions of ideology are fourfold: to legitimate, mystify, motivate and control.

Figure 1.1: How Ideology, Physical Force and Economy create the political terrain (from Maisels 1984, 283).

This is a book about what caused the rise of the state. I define the state as control over people and territory exercised from a centre through specialized apparatuses of power that are: (1) military; (2) administrative (mostly tax-raising); (3) legal and (4) ideological. I define power simply, following Schortman, Urban and Ausec (1996: 62), as “the ability to direct and benefit from the actions of others”.

As for political power, Garth Bawden (2004: 118) has a very neat formulation: “At its most basic level, political power denotes the ability of an agent to advance partisan interests in the face of opposition. As such it is a universal accompaniment of human society, exercised in all aspects of human discourse”. Power, however, is not to be understood simply as manifest or latent force, but also, importantly, as the ability to set the social agenda such that meaningful opposition does not arise. Hence the importance attached in this work to ideology, which, when successful, convinces others with objectively different interests, that in fact there is a community of interest.

As for the political power of the state, John Locke (1689) is at his most pithy: “Political power, then, I take to be a right of making laws with penalties of death, and consequently all less penalties, for the regulating and preserving of property, and of employing the force of the community…” (An Essay Concerning the True Original Extent and End of Civil Government).

The mechanism for the generation of power is the ability to command sufficient amounts of ideological, economic or physical-force resources in a given situation, to advance one’s own interests or to block or deflect those of others advancing their interests at one’s expense. A state usually commands more of those three key resources and so normally wields the greatest power. Of course states differ in power relative to one another, according to their ability to mobilize and manage different quantities of those resources (Hui 2005). But a state needs ideological justification to be considered legitimate and thus stable; cathedrals are required as well as castles. Natural disasters, failure in war on in economic adequacy will strip away its ideological cover – religion, ethnicity, nationalism, tradition – and the state, or at least the regime, will fall, depending on the seriousness or cumulative nature of the failures. Russia in 1917 and again in 1991, are major examples in the last century. Now I can define the state simply as: a coercive centre of ideological, physical and economic force.

Ideology has those defining characteristics: (1) it is the public representation and justification of private or sectional interests, which (2) can be material or immaterial, real or imagined, while (3) the fact that the ideology represents and furthers the interests of a particular group is disguised by the claim of ‘universal benefit’, and/or the claim that ‘high principles’ are involved which are in the interests of the whole of the nation, society, or humanity; from which it follows that (4) ideological justification selects only those facts that can be spun as favourable to its claims with counter-facts ignored, denied, denigrated or suppressed. Thus (5) ideology can combine with the emotions to such an extent that it is no longer thought but felt; ideology is then experienced as an emotion.

One either spins or adopts an ideology to represent one’s own interests, or one is entrained in the ideology of others. It is the all-embracing, potentially all-consuming nature of ideology that makes it so dangerous. Its psychological sources are threefold:

(a) in the stories we tell ourselves about our motivations, (b) in the excuses we make for ourselves about our actions, and (c) in the phenomenology of everyday life, that is, in the way that the natural and social environment appears to us. For example, on the patt ern of human experience, natural processes appear to be agent driven, the consequence of ‘will’, hence the universal belief in spirits and deities as transempirical entities accounting for empirical processes that are not understood (Boyer 2001: 160–161), when in fact it is our own cognitive processes, specifically our use of ontological categories (‘templates’), that we don’t understand (ibid.: 90, 109).

(Self-) interest of groups, individuals or institutions, is what distinguishes ideology from failed science. This is equivalent to the difference between a lie and a mistake. A lie is a deliberate falsehood, whereas a mistake is simply an error in attempting to tell the truth. Pre-Newtonian science thought that planetary orbits were circular rather than elliptical. This was a mistake, not a lie. But lying to oneself helps convince others that one’s self-interested claims are for the general good, as Frank (1988: 131) explains: “If liars believe they are doing the right thing, observers will not be able to detect symptoms of guilt because there will not be any. With this notion in mind, Robert Trivers suggests that the first step in effective deception will be to deceive oneself, to hide ‘the truth from the conscious mind the bett er to hide it from others.’ He describes an evolutionary arms race in which the capacity for self-deception competes for primacy against the ability to detect deception.

“Extensive research shows that self-deception is indeed both widespread and highly effective. People tend to interpret their own actions in the most favourable light, erecting complex belief systems riddled with self-serving biases” and lots of excuses; even excuses for making excuses. So when ideology fails, as it must, more ideology is slapped on top to cover it up, in a potentially infinite regress until reality hits really hard.

Claims to special privilege, especially the ‘right’ to rule, are most stable when other social groups can be convinced that partisan interests are not really partisan, but are in fact universal; beneficial to society as a whole because of some special role that the interest group has (e.g. in ritual) or some special skill that it possesses (e.g. in warfare). A dominant

(i.e. rulers’) ideology forms in this manner by “condensing the conceptions that represent reality for its adherents and affirming those to the public at large through codified visual symbolism and participatory ceremonies” (Bawden 2004: 119); also by verbal narrative and pronouncement. A ruler’s ideology is most stable when it can shape worldview:

“Ideology is driven toward ‘deriving’ its social myth from a world-view, a Weltanschauung. We might call this ‘method’ of world-mythologizing the method of ‘isomorphic projection’. In other words, the same structural traits which characterize the social myth are projected on the world as a whole as a total myth. Then, after this projection has been accomplished, the ideologist claims to ‘derive’ his social myth as a special case of world myth” (Feuer 1975: 99).

Ultimately everything is about power and its prerogatives; consider the power pyramid where you work. Two further tropes are commonly used by ideologists: (1) if you can invoke ‘the general good’ for a proposition, then you can sell it as ‘principle’, and an antisocial act or political position can be justified by appeal to ‘principle’ or ‘conscience’, despite its adverse impact on the public good, rhetoric and reality being different things; and (2) the hiding of a politico-ideological agenda behind alleged ‘practicalities’. So instead of coming out and admitting that one is opposed to certain things on ideological grounds – which would admit interest – one says that certain laws or initiatives should not be implemented because they are ‘counterproductive’, ‘excessive’, ‘impossible to administer’ or just ‘unfair’, a suitably vague term.

Art is part of the currency of power. To be effective, power must be felt by a population as both latent and present, implicit and explicit. This combination is manifest in art, ritual and ceremonial. All three are forms of display that stop short of the actual use of force, but all three can readily be combined with displays of the naked instruments of power, as at Nuremberg Rallies or parades through Red Square. The balletic qualities of such rallies are part of their imp...