![]()

CHAPTER 1

ANGOLAN ARMED FACTIONS

Angola is a beautiful country in south-western Africa. As the seventh largest nation on this continent, it includes a huge area with very diverse geography and population. Crucial for the developments in this country during the period 1975-1976 were a number of armed nationalist groups that had emerged during the last decade of more than 400 years of Portuguese colonial rule. This chapter therefore provides a review of the country, its geography and the population, and the four crucial armed groups existent as of 1975-1976.

Geography and People of Angola

Although having a rich history of inhabitation dating back to the Palaeolithic Era, next to nothing is known about this area before it was carved into its modern-day form by the Portuguese conquests, starting in 1483. While the natives initially welcomed the newcomers, and in 1491 the most powerful local ruler – Manikongo (‘king’) Nzinga Nkuwu – converted to Christianity and accepted foreign guidance in the administration of his realm, the Portuguese were exclusively interested in extracting profit from a booming trade in slaves. Aided by local chiefs, the slave traffic gradually undermined the authority of the manikongo, and resulted in the collapse of the native state. All that was left from earlier periods was the title of the local ruler, ‘ngola’ – which eventually transformed into the name of the area. Subsequently, the Portuguese had extended their reach southward from the area of present-day Luanda, founded in 1575, and started claiming colonial authority. Luanda was briefly held by the Dutch, in the 17th Century, but with the slave trade dominating the local economy the Portuguese quickly re-established themselves in the dominating position. Nevertheless, no European settlement took place even as of the 19th Century: on the contrary, an estimated three million people had been taken away and sold off across the Atlantic, primarily to North America, by that time.

The geography, and thus the terrain, of Angola can be divided into three major regions. From west to east, these are the coastal plain, a transition zone, and the (vast) inland ‘plateau’. The low-lying coastal plain is between 50 and 150 kilometres (30-90 miles) wide. The transition zone – dominated by terraces or escarpments – is about 150 kilometres (90 miles) wide in the north, but narrows down to about 30 kilometres (20 miles) further south. The vast Angolan plateau covers approximately two thirds of the country and has an average elevation of 1,100 to 1,520 metres (3,300 to 5,000ft) above sea level.

While having no sizeable lakes, Angola is rich with water resources. Most of the rivers – foremost the Cuanza and the Cunene – rise in the central mountains before draining to the Atlantic Ocean, while the Kwango River drains into the huge Congo River system. The climate in most of the country is tropical, with a dry season from September to April, but the cool Benguela Current moderates the temperatures in the coastal region, and brings most of the rainfall. On the contrary, the cooler central plateau receives much less water. Vegetation varies with the climate: there are thick tropical rain forests around the north and in the Cabinda enclave; savannah and a few rain forests in the centre, and a land of mixed trees and grasses in the south and the east. Wildlife is as diverse and includes many of the larger African mammals, from elephants and rhinoceroses, to giraffes, hippopotamuses, zebras, various antelopes, lions and even gorillas. Angola is immensely rich in mineral resources, foremost including petroleum and diamonds, but also iron ore, manganese, copper, uranium, phosphates, and salt.1

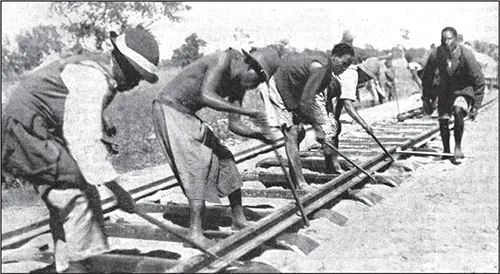

Work underway on the Benguela Railway, constructed by the Portuguese in the 1930s. (Mark Lepko Collection)

Although usually perceived as ‘monolithic’ by foreigners, the composition of the population of Angola is at least as diverse: it is made up of more than 90 different ethnic groups. Just five of these groups make up more than 90% of the population though: Ovimbunda (37%), Mbundu (25%), BaKongo (15%), Lunda-Chokwe (8%) and Nganguela (6%). The distribution of the population was just as uneven: nearly 70% used to live in the coastal regions, especially in the north; even as of today, only about 35% of Angolans live in the urban areas. Perhaps more importantly, for decades after Angolan independence, for the majority of the country’s population there was no ‘Angola’ as one unified nation and a country: all that mattered was the ethnic group in control of the nearby area, and what their tribal chiefs said.

While easily suppressing any forms of native resistance, Portugal gained full control of Angola’s interior only in the early 20th Century. Henceforth, the country was governed under the so-called regime do indigenato, an invidious system of economic exploitation, educational neglect, and political repression. Certainly enough, in 1951 the colony’s official status was changed to that of an overseas province and then the policy of an accelerated European settlement was adopted. Over the following 20 years, up to 400,000 Portuguese colonists moved in, and especially cities and major towns experienced rapid development. Luanda grew into a bristling metropolis with a major port and airport, and similar happened in Novoa Lisboa (Huambo), Porto Amboim (Benguela Velha), the port of Lobito and Sa de Bandeira (Lubango) (for a review of colonial and postindependence names for local cities, see Table 1). It was during the same period that most of about 51,400 kilometres (around 32,000 miles) of roads existent as of our times were constructed – of which fewer than one tenth were ever paved. Furthermore, the Portuguese constructed about 2,950 kilometres (1,835 miles) of railroad track – including the principal line – the ‘Benguela Railway’ – linking mineral-rich Zambia and the Katanga Regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with the port of Lobito on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean. Nevertheless, the road and railroad networks of Angola remain seriously inadequate for a country of this size until this day, and were thus largely supplemented by relatively well-developed internal air services by the early 1960s, by when at least a dirt strip was constructed next to every larger settlement.

The City Hall of Luanda in the 1960s. (Mark Lepko Collection)

However, this was little other than an attempt to stave off the inevitable: local nationalist movements were meanwhile experiencing rapid growth, and in 1961 a guerrilla war against the Portuguese was initiated. Contrary to Mozambique and Guiné, and from the onset of their struggle for independence, the Angolan nationalists were divided into several rival movements. Differences between these often reached such dimensions that some of the movements in question preferred to collaborate with the Portuguese against each other. Despite several attempts at political unification, combatants from diverse factions preferred to fight each other rather than cooperate. Thus, although the conflict of the 1960s and 1970s is usually called the Angolan War of Liberation, and as such separated from the subsequent Angolan Civil War, the matter of fact is that the Angolan civil war had been going on already since the 1960s: this intra-nationalist power struggle only remained unknown to the wider public because the Portuguese war against the nationalists attracted most attention. Unsurprisingly, and for all practical purposes, a full-fledged conflict was clearly in the making already at the time the Portuguese announced their withdrawal in 1974. The principal issue was that – because of successful Portuguese counter-insurgency (COIN) campaigns – all three major nationalist movements existent at the time were weakened to a degree where none was capable of launching and running a conventional, or at least semi-conventional, military operation to bring the huge country under its control.

Table 1: List of City/Town/Locality Names of which have changed since 1975

| Colonial Name | New Name |

| Amboim | Gabela |

| Ambrizete | N’Zeto |

| Benguella | Benguela |

| Carmona | Uige |

| Gago Coutinho | Lumbala |

| Henrique de Carvalho | Saurimo |

| Luso | Luena |

| Mocamedes | Namibe |

| Nova Lisboa | Huambo |

| Novo Redondo | Sumbe |

| Porto Amboim | Gunza |

| Pereira de Eça | Ongiva |

| Porto Alexandre | Tombwe/Tombua |

| Roçades | Xangongo |

| Vila Robert Williams | Caála |

| Sá de Bandeira | Lubango |

| Salazar | N’Dalatando |

| Santa Comba/Cela | Waku-Kungo |

| Santo Antonio de Zaire | Soyo |

| Sao Salvador | M’banza-Kongo |

| Serpa Pinto | Menongue |

| Silva Porto | Kuito |

| Teixeira da Silva | Bailundo/Bailunda |

| Teixeira de Sousa | Luau |

| Xamindele | Toto |

| Vila Luso | Luena |

| Vila Salazar | N’dalatando |

FNLA (and ELNA)

One of the first movements of Angolan nationalists – the Angola’s People’s Union (Uniao das Populações de Angola, UPA) – was established in 1954. The leader of the UPA was Holden Roberto – a youngster from the BaKongo tribe, educated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where he subsequently worked as a clerk for the Belgian colonial administration. Maintaining a very tight grip on ‘his’ movement and making virtually all of the important decisions, Roberto thus turned the UPA into a movement of the BaKongo, while failing to make it attractive for other ethnic groups. Furthermore, his movement placed very little emphasis on political work, while his cadre became renowned for their corrupt practices: amongst others, Roberto is known to have diverted funding for financing various of his private ventures. Despite such shortcomings, the UPA – which was reorganized as the Angola National Liberation Front (Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola, FNLA), on 27 March 1962, soon after a merger with a smaller BaKongo political movement – remained the most powerful national movement of the mid-1960s. One reason is that Roberto managed to maintain close relations to the successive Congolese (and then Zairian) heads of state, including Patrice Lumumba, Cyril Adoula, and Major-General Joseph Mobutu. Indeed, Roberto even had family ties with the latter, who seized power in 1965. Correspondingly, the FNLA could always count on steady support from Congo/Zaire, and was even permitted to make use of that country as its base. In turn, Roberto grew over-dependent on Mobutu, and thus found himself outside the position to act without his consent. Furthermore, the FNLA experienced a number of setbacks on the international plan during the late 1960s, because numerous foreign governments began supporting other insurgent movements instead.2

The armed wing of the FNLA was the Angola National Liberation Army (Exército de Libertação Nacional de Angola, ELNA). Ironically, this was officially established just a few months after the movement triggered the beginning of the Angolan War of Liberation by launching its most successful operation against the Portuguese ever. In mid-March 1961, thousands of UPA’s untrained and poorly- armed combatants penetrated northern Angola – left virtually undefended by the Portuguese, who were thus taken by surprise – and destroyed hundreds of administrative posts, farms and coffee plantations, killing hundreds of European settlers and thousands of Africans. In a matter of weeks, the UPA – which reinforced its ranks through forceful recruitment of the local villagers – then established itself in control of nearly all of the BaKongo-populated parts of Angola. Only hastily created settler militias managed to protect the various settlements from being overrun by insurgents. With a mere handful of the insurgents having any kind of military training (most of these were defectors from the Portuguese Army), the UNLA had no means of preventing the colonial military from deploying reinforcements and then recovering all of northern Angola before launchung their own ruthless repression in May 1961.3

Following its expulsion from Angola, the remnants of the UPA were re-organized as the ENLA and benefitted – immensely – from the support of the Congolese authorities. In August 1962, it established its most important base near Kinkulu, while its headquarters (HQ) was located in Leopoldville (re-named to Kinshasa, in 1966). The movement began benefiting from support provided by Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco too and had some of its cadre trained abroad during the following years. Furthermore, in addition to receiving around 70 tonnes of arms and ammunition from Algeria and Tunisia in 1963, it received some financial support from private US associations, such as the American Committee on Africa.

Although the combination of safe bases in the DRC and the jungle-covered northern Angola was offering ideal terrain for an insurgency, the ELNA limited itself to small scale, hit-and-run operations across the border. These usually involved groups of between...