- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A simple, easy-to-use guide for British family historians wishing to trace their female ancestry.

Everyone has a mother and a line of female ancestors, and often their paths through life are hard to trace. That is why this detailed, accessible handbook is of such value, for it explores the lives of female ancestors from the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 to the beginning of the First World War.

In 1815, a woman was the chattel of her husband; by 1914, when the menfolk were embarking on one of the most disastrous wars ever known, the women at home were taking on jobs and responsibilities never before imagined. Adèle Emm's work is the ideal introduction to the role of women during this period of dramatic social change.

Chapters cover the quintessential experiences of birth, marriage, and death; a woman's working and daily life, both middle and working class; through to crime and punishment, the acquisition of an education and the fight for equality. Each chapter gives advice on where further resources, archives, wills, newspapers, and websites can be found, with plentiful common-sense advice on how to use them.

"A unique and information packed instructional reference and guide, Tracing Your Female Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians is an extraordinary and thoroughly user friendly manual that is unreservedly recommended for both community and academic library Genealogy collections and supplemental studies lists." — Midwest Book Review

Everyone has a mother and a line of female ancestors, and often their paths through life are hard to trace. That is why this detailed, accessible handbook is of such value, for it explores the lives of female ancestors from the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 to the beginning of the First World War.

In 1815, a woman was the chattel of her husband; by 1914, when the menfolk were embarking on one of the most disastrous wars ever known, the women at home were taking on jobs and responsibilities never before imagined. Adèle Emm's work is the ideal introduction to the role of women during this period of dramatic social change.

Chapters cover the quintessential experiences of birth, marriage, and death; a woman's working and daily life, both middle and working class; through to crime and punishment, the acquisition of an education and the fight for equality. Each chapter gives advice on where further resources, archives, wills, newspapers, and websites can be found, with plentiful common-sense advice on how to use them.

"A unique and information packed instructional reference and guide, Tracing Your Female Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians is an extraordinary and thoroughly user friendly manual that is unreservedly recommended for both community and academic library Genealogy collections and supplemental studies lists." — Midwest Book Review

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tracing Your Female Ancestors by Adéle Emm in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781526730145Subtopic

British HistoryChapter 1

BIRTH, MARRIAGE AND DEATH

According to family myth, we were ‘diddled out’ of Tickford Abbey in Newport Pagnell because ‘there were only girls’. I dismissed this as far-fetched until I discovered an 1840s family with four daughters, Hooton, the same surname as the builders and original owners of the Abbey. The law of primogeniture, where an estate and inheritance is passed to the firstborn male, was crucial and explains HenryVIII’s obsessive craving for a legitimate son. In aristocratic and privileged circles with an estate to inherit, brothers, no matter in which order they were born, inherited before sisters and the son of a deceased elder brother had precedence over everyone else. It wasn’t until the 1925 Administration of Estates Act (England and Wales) that this was addressed.

Put simply, boys were more important than girls.

BIRTH

Giving birth was incredibly dangerous for a woman regardless of her status in society, Queen Victoria included. Even though the medical fraternity underplayed the danger by claiming it was ‘only six to seven per cent’ who didn’t survive, many a literate wife wrote a fond farewell letter to her husband in case she died.

Unlike today, there wasn’t a reliable form of contraceptive and each successive pregnancy increased the risk of a woman’s death. The first viable form of family planning other than abstinence was Charles Goodyear’s 1839 invention of rubber vulcanisation and, from the late 1850s, mass-production of rubber condoms. This reusable thick-seamed sheath was unconducive to harmonious relations with a naïve wife, but prevented rakish men contracting venereal disease from prostitutes. Family planning as we know it today was the mission of Marie Stopes (1880–1958), only really taking off post the First World War.

The fashionable management of a woman in a ‘delicate condition’ in the early half of the nineteenth century was to be bled by leeches and follow a strict diet, thus ensuring a smaller baby and subsequently easier delivery.

Such was the treatment ministered in 1817 to Princess Charlotte, the only child of the Prince Regent (later George IV), who, according to the Oxford Journal, 1 November 1817, rose at nine, breakfasted with her husband, Prince Leopold, and spent much of her time resting in a garden chair. So thrilled was the populace by her pregnancy, betting shops speculated on the gender of the forthcoming child. She went into labour at Claremont House but, when baby was diagnosed as transverse, the doctors dithered about the delivery. After fifty hours of labour and no painkiller, the poor woman gave birth to a 9lb stillborn son. Still haemorrhaging from medical mismanagement (forceps were out of favour) and convulsions, she too died. She was 21.

Queen Victoria’s first child, daughter Princess Victoria (1840–1901) was born following a twelve-hour labour and only her last two out of nine, Prince Leopold (1853–84) and Princess Beatrice (1857–1944), were born with the aid of a new technology, chloroform. Following her physician’s 1858 publication of the ground-breaking book, On Choloroform and Other Anaesthetics (see https://archive.org/details/onchloroformothe1858snow), Dr John Snow (1813–58) ensured pain relief in childbirth was finally a reality – for the privileged.

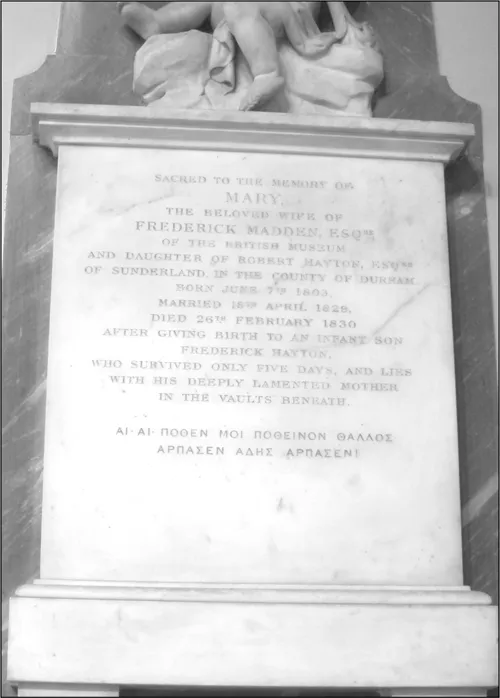

If death and acute pain occurred in royal circles, imagine how much worse it was for an ordinary woman. Breech births were dangerous complications (as now) and if a doctor resorted to a caesarean, the mother usually died. Doctors and fathers faced an impossible decision; save mother or baby. At a time when some barbaric implements were used to extract foetuses and babies, both mother and infant usually died. Once baby was delivered, there was the danger of afterbirth, possible haemorrhaging and infection. An infant’s name appearing on a gravestone with its mother, or a child registered as ‘male’ or ‘female’, was a child who died at or shortly after birth.

Memorial to Mary Madden who died in childbirth 26 February 1830 and son Frederick who died aged five days. St George’s Church, Bloomsbury.

Only the middle class and gentry had access to physicians. Everyone else resorted to family members, mother, mother-in-law or local midwife (old English mid ‘with’ and wif ‘woman’; with the woman). Synonyms for giving birth included lying-in, accouchement (an accoucheur was a male midwife, first known use 1727), parturition, childbed, birthing, confinement and travail.

In 1877, Thomas Bull published his 26th edition of Hints to Mothers for the Management of Health during the Period of Pregnancy and in the Lying-in-Room. It advised on diet, morning sickness, prevention of miscarriage, labour, management post childbirth, wet and dry nursing and weaning. He recommended new mothers lie recumbent for at least four days, warning, ‘Among the poorer classes of society, who get up very soon after delivery, and undergo much fatigue, the “falling down of the womb” is a very common and distressing complaint’. His suggestion, ‘a bandage, wide enough to cover the whole length of the abdomen, is to be applied directly after delivery’, adding this was especially useful for women with many children in quick succession or who are ‘short and stout’. An indirect reference to Queen Victoria perhaps?

The middle classes employed monthly nurses for the lying-in period of four weeks following birth.

For the working class, there was no prissy rest and relaxation whilst pregnant or after delivery. Mum worked up to the delivery date, returning as soon as possible after the birth. Only in 1891 was a law passed (Factory and Workshop Act) prohibiting factory owners employing women within four weeks of childbirth. It applied to women working in factories but two years later was extended to eleven weeks after birth for all working mothers.

Wet nursing was commonplace, especially for the gentry who considered breastfeeding distasteful. Middle- and upper-class babies could be sent away for up to three years until fully weaned. Both wet and dry nursing were frowned on by the medical fraternity concerned with appalling neo-natal and childhood death rates. Dry nursing was putting a baby to a non-lactating breast for comfort whilst feeding baby whatever solid food was available. In 1862, physician M.A. Baines complained ‘fashionable’ wet and dry nursing was ‘most disastrous in a sanitary and social point of view’.

A wet nurse had to be acquired, often a woman who had just lost her baby. It was not well paid. The more privileged demanded a superior wet nurse. Before confinement and on behalf of his patient, physicians advertised in local newspapers for a respectable married woman with several children willing to take on another. Respondents applied by letter which implied literacy. Wet nurses also advertised themselves through this medium and word of mouth, plus local knowledge was useful to both parties.

In the tragic case of Princess Charlotte, the Royal Physician Sir Richard Croft interviewed a married woman with three children for a position offering an extraordinary salary. Her children were medically examined to check they, too, were fit and healthy. For reasons of discretion, he and his colleagues spoke French during the interview not realising the (unnamed) prospective wet nurse understood – she informed them part way through the interview. On 1 November 1817, the Leicester Chronicle reported the remuneration – for a prince, a one-off payment of £1,500 plus £200 a year. It admitted not knowing the fee should Princess Charlotte deliver a daughter.

Why did Sir Richard Croft go to such lengths in choosing a wet nurse? Survival rates for a wet nurse’s own baby and the child she was nursing were appalling. In 1859, 184,264 children under the age of 5 died. This represented two in five deaths that year for all ages; 105,629 were under 1 – a total infant mortality of 45 per cent. Several reasons were advocated. Protesting this figure was higher than for animals, Sir Arthur Leared, Physician to the Great Northern Hospital, Manchester, blamed young women and mothers for working in factories, accusing them of abandoning children for money. An educated privileged man, he ignored or was not apprised of the fact that many worked through sheer necessity, especially if their husbands were unemployed. However, supporting his theory, infant mortality fell during the Lancashire Cotton Famine (1861–5) – it was assumed because women were forced to stay at home and directly care for their children.

Another explanation for low infant survival was diet. Godfrey’s Mixture or Cordial, a brew containing laudanum and treacle with the dual benefit of filling baby’s tummy and sedating it at the same time, was popular with mothers in the textile industry. Also, during the mid–1800s food was heavily adulterated, especially milk and bread which inadvertently poisoned wet nurse, mother and infant, sometimes causing the death of all. In the workhouse, babies often received totally unsuitable – but cheap – food.

Hetty and Albert Harris, 1913. Author’s collection © Adèle Emm

Today, baby blues, or postnatal depression, is well recognised. Our ancestors regarded it as a form of insanity and/or melancholia. Should a female ancestor be admitted to an asylum a few months after childbirth, this could have been the cause. Bethlem Hospital Archives (http://museumofthemind.org.uk) include photographs of named women treated for insanity following postnatal depression, infidelity, over-work, alcoholism, senile dementia, anxiety and epilepsy etc. A psychiatric hospital since 1247, it allows personal visits by appointment and some records are accessible via FindMyPast (www.findmypast.co.uk/bethlem).

A surviving family Bible is a cherished source of dates for births, marriages and deaths. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, announcing a birth in the personal columns of the local paper became popular even for those of a less moneyed background. Once the cost of photography was within the reach of ordinary folk, it became widespread from the 1880s for mother and baby to have their photograph taken in the nearest studio, usually around the christening date. Such photographs are common in family albums; the trick, of course, is recognising who they are.

Illegitimacy

Up to civil registration 1 July 1837 and beyond, baptisms were recorded in the parish register. If there’s no name in the father’s column, the baby was illegitimate. For a few years after civil registration, not everyone understood children had to be registered separate from baptism so, for a while, some births are only found as christenings in the church register.

If, after 1837 there was no name in the father’s column of the birth certificate, it’s also highly likely the child was illegitimate. Children could be registered without parents being married so you may find parents married after a ba...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedicaton

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Note on Money

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Birth, Marriage and Death

- Chapter 2 Education

- Chapter 3 Crime and Punishment

- Chapter 4 Daily Life

- Chapter 5 A Hard Day’s Work

- Chapter 6 Emancipation

- Timeline