![]()

1

The Officer Corps

At the beginning of the Thirty Years War there were no standing armies: instead countries and states had to rely on civic guards or local militias which were called out in emergencies such as periods of unrest. Therefore when the war the broke out few had any experience of fighting or commanding troops. Although the Thirty Years War officially began on 23 May 1618 with the Defenestration of Prague, it was not until 8 October 1619 that Elector Maximilian of Bavaria, as head of the Catholic League, agreed to raise an army of 30,000 men by the spring of the following year. Commissions were sent out to the nobility and the gentry bestowing their military position and detailing, how many men they were expected to raise, and the number of companies or troops that would make up the regiment. A typical infantry regiment usually consisted of 3,000 men; although commissions for 1,000 and 2,000 men were also known, when Levin von Mortaigne was appointed colonel he was commissioned to raise 3,250. Cavalry regiments varied greatly in strength but on average were about 500 strong. Once the colonels had been appointed then they would, in theory, send out commissions appointing men to command the various troops or companies within their regiments. In practice a head of state might ‘suggest’ an officer they could appoint to a position.1

Moreover when a colonelcy of a regiment became vacant there was no guarantee that the lieutenant colonel would be chosen to command it: Lieutenant Colonel Hans Wolf von Salis petitioned Maximilian three times before he became a colonel. Sometimes Maximilian’s candidate was not always accepted by the regiment, for example when the colonelcy of the Würzburg Regiment of Foot became vacant in 1621 Maximilian appointed Count George Ernst von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as its colonel. However, the regiment mutinied because they wanted Wolf Dietrich Truchsess von Wetzhausen, their lieutenant colonel, to be appointed to that position. Both officers and men petitioned Johan Bishop of Würzburg, who had raised the regiment, and when he sided with them Maximilian was forced to back down and Count George Ernst was given a commission to raise a new regiment instead. The Elector may have held a grudge against the Würzburg Regiment as it was almost always the last to be paid.2

It has been estimated that a colonel needed between 400,000 and 450,000 fl per year to maintain a regiment of foot 3,000 strong, and 260,000 to 300,000 fl for a regiment of 1,200 cavalry. Fortunately for the colonels very few regiments mustered this strength so the outlay was much smaller, with a regiment of horse rarely mustering more than 500 strong, particularly during the latter part of the war. Nevertheless when Otto Heinrich Fugger raised a regiment for the Spanish service at the beginning of the war it cost him 50,000 guilders. Despite coming from a wealthy Augsburg banking family, he had to borrow much of the money from them and obtain loans of between 1,000 and 15,000 guilders at 5–6 percent interest per annum. He was still paying back the money for this regiment when he died in 1644. When he entered Bavarian service in 1631 he commanded another regiment, as well as taking over Johann von Tilly’s Regiment of Foot on 30 December 1632. He would still have had to pay for the upkeep of these regiments until he was reimbursed by Maximilian, although this might be some time coming.

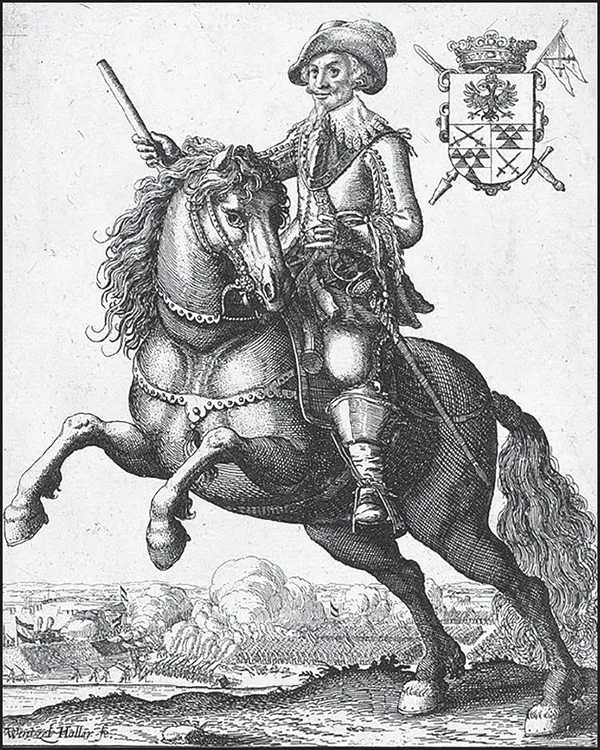

1. Johann von Tilly, one of the chief commanders of the Imperial forces in the initial half of the Thirty Years War.

Apart from the ‘Long War’ with the Ottoman Empire, and the Dutch Revolt, which from 1609 was enjoying a 12 year truce, many officers had little or no experience in warfare, but being part of the nobility they were expected to serve. This was alright if they were cut out for a military life, but others, like the Imperialist General Federico Savelli, were forced into soldiering: Savelli by his father, Duke Bernard de Savelli. True, Federico had served in the Long War and had been the commander of the Papal forces, but in February 1631 when he surrendered Demmin to Gustavus Adolphus after a brief siege, Gustavus advised him to serve the Emperor at court rather than in the army. Nevertheless, Savelli went on to serve at the siege of Magdeburg and at the battle of Breitenfeld, after which Ferdinand sent him to assist Pope Urban VIII. Despite never being happy when he was soldiering, he returned to army life in 1635 and became a Field Marshal in 1638. Whether he was trying to prove himself, or his military rank compelled him to do so, he insisted on commanding the advance guard of the Imperialist Army himself and blundered into a narrow pass at Wittenweier, where he was defeated by Bernard of Saxe-Weimar on 30 July 1638. According to Franz Redlich he was to be court-martialled for this, but his aristocratic status prevented it and instead he returned to the diplomatic life.3

Another veteran of the Long War had a very different experience. Johann von Tilly was born in South Brabant in 1559 of a noble family. He served with the Spanish Army under the Duke of Alva in 1580, before entering Imperial service in 1598. After the peace with the Ottoman Empire he entered Bavarian service commanding the state’s militia. So by the outbreak of the Thirty Years War he had considerable experience in warfare and Maximilian appointed him commander of his army.

Unfortunately, he is best remembered for the sack of Magdeburg and his defeat at the battle of Breitenfeld in 1631, but he was one of the best generals of the Thirty Years War, although he has been overshadowed by Gustavus Adolphus and Wallenstein. It was said that a fog had come down during the battle of the Lech which obscured the Swedish movements, which prompted Tilly to confess to the Duke of Bavaria that ‘he had no good opinion of his actions, seeing daily heaven and earth did favour and second the King of Sweden.’4

Despite being 72 by this time he was wounded at Breitenfeld, and mortally wounded at the crossing of the River Lech, which opened Bavaria to invasion by the Swedish. Scottish officer Robert Monro admired Tilly, of whom he records,

Wherein we have a notable example of an old expert General, who being seventy two years of age, was ready to die in defence of his Religion and Country, and in defence of those whom he served … [which] should encourage all brave Cavaliers … to follow his example in life and death.5

After Tilly’s death Maximilian appointed Lord Grants to succeed him, but he was described as not being ‘beloved nor respected’ by his men and so seems to have been sidelined, and the rank Tilly held appears to have remained vacant. Whether appointed by patronage or merit it was important that an officer had the respect of his fellow officers, and as Robert Monro points out, ‘When officers and soldiers conceive an evil opinion of their leaders, no eloquence is able to make them think well of them thereafter … [and they] are despised by their followers.’6

Monro also admired General Gottfried von Pappenheim whom he describes as ‘a worthy brave fellow, though he was our enemy his valour and resolution I esteemed so much.’ He added that if an enemy army was near him they could ‘never [be] suffered to sleep sound’ for fear they would be attacked by him.7

Pappenheim was born on 29 May 1594 in Treuchtlingen, Bavaria. His father died when he was only six years old and his mother married Adam von Herbersdorf. In 1616 he converted to Catholicism, and when the war broke out his status and the patronage of his stepfather guaranteed him a high position within the army, even though he had no military experience. At first he was a captain in Herbersdorf ’s Regiment of Cuirassiers, becoming the regiment’s lieutenant colonel by October 1621. In April 1622 Pappenheim had become a full colonel; two years later he entered Spanish service, but was recalled in 1626 to help Maximilian put down the rebellion in Upper Austria. In November 1630 he rose to the rank of field marshal of the Catholic League; he seems to have fallen out with Tilly during the siege of Magdeburg and so transferred to Imperialist service without too much difficulty, although no doubt much to the sorrow of Maximilian and Tilly at the loss of a good general. However, Pappenheim was killed at the battle of Lützen on 16 November 1632.

2. Gottfried von Pappenheim, the cavalry general whose reputation was tarnished by his actions at Breitenfeld.

Gottfried von Pappenheim left only one son, Wolfgang Adam von Pappenheim, who was born in 1618. Despite his age the status of his family was such that he succeeded his father as the colonel of his regiment of foot in 1632. However, the regiment would be commanded by its lieutenant colonel, Hans Ulrich Gold, until Wolfgang was old enough to command it in person. He was eager to take command of his regiment, which brought about several demands to Maximilian over the years. At the siege of Hohenasperg his regiment lost 400 men in two weeks while under his command, trying to storm the town. He was killed fighting a duel with Colonel Colloredo in Prague on 30 June 1647. Another Pappenheim to serve in the army was Phillip von Pappenheim who was Gottfried’s cousin, although he only rose to the rank of captain.8

The highest rank in the Bavarian Army was field marshal, which would be held by six men during the war, including Johan Jakob Count von Anholt. In 1620 Anholt was appointed colonel, then major general of foot and then major general. Two years later he was appointed field marshal and second only to Maximilian and Tilly in command of the Bavarian Army. Other field marshals included Joachim von Wahl who had been a captain in 1620 and by 1626 had become the lieutenant colonel of Tilly’s own regiment of foot. He became field marshal on 29 May 1640, however in 1644 due to ill health he was appointed the governor of Ingoldstadt so that he could still enjoy his status as an officer. He was succeeded by Franz Freiherr von Mercy, who was killed at the battle of Allerheim on 3 August 1645.9

3. Johann von Werth, an able cavalry commander who was able to raid deep into France.

Of course, not all officers reached the heights of field marshal. There would be 11 generals of cavalry or general of the ordnance, five lieutenant field marshals and 21 major generals. True, the higher up the social ladder a person was the higher command he was initially appointed to. However, this is not to say that all the officers came from the nobility. Between 1635 and 1649 the army consisted of 13 regiments of foot, 16 of horse and two of dragoons commanded by 51 colonels; of these only 16 came from the nobility, the rest from gentry or peasant families, although of the army’s generals 18 out of 22 were from the nobility. Whereas in the Imperialist Army in 1633 only 13 out of 107 colonels were commoners, although this number was slowly rising as the war progressed.10

Among those officers who came from a peasant family was Johann von Werth who was born in 1594 and enlisted as a trooper in the Spanish service in the Netherlands. In 1631 he transferr...