![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Early Navy Operations in Vietnam

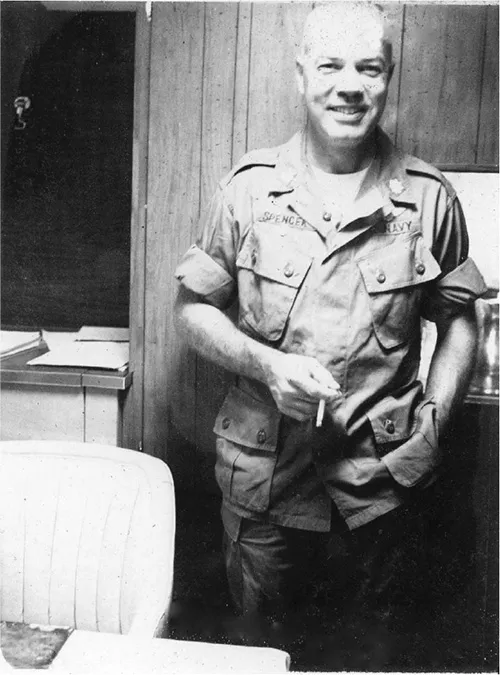

Bob Spencer: “Gentlemen, it’s time to build a squadron.”

Commander Spencer standing in his office.

(Courtesy of Seawolf family)

It was in 1966 that the United States Navy began to expand its nascent riverine warfare operations in the Mekong Delta using small craft called PBRs (Patrol Boats, River). The watercraft were needed to enable America’s naval forces to conduct day and night patrols to keep the commercial traffic flowing throughout the vast network of rivers used in transporting rice from the Mekong Delta rice bowl to the great northern urban population center around Saigon, the capital of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam).

Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara, granted initial authorization for the watercraft in August 1965, and it was a month later that Navy brass met in Saigon and decided to assemble a force of 120 boats to patrol the Mekong Delta and the Rung Sat Special Zone, with the expansion target date of early 1966. Not long afterward, on December 18, the River Patrol Force was created under the code name Operation Game Warden and designated Task Force 116. 1

Early in the war, the U.S. Army had begun to assert its increasing presence in the southern part of the country designated as IV Corps and had already been tasked to protect the 31-foot boats trying to interdict enemy vessels and tax collectors on the delta’s rivers and canals. Attacks on Vietnamese sampans and junks from along the riverbanks were so frequent and severe that many local rice farmers had to resort to transporting their harvest by a much longer route, traveling northwestward to the Cambodian border to successfully complete the trip. Consequently, the primary mission of the newly arrived Navy boats was to keep the rivers open to enable processed rice to move northward via the shortest route.

Aggressive patrolling by the heavily armed and speedy, but fragile fiberglass PBRs resulted in more frequent attacks by the ever-present yet elusive black-pajama-clad Vietnamese Communist fighters. The consequence of these attacks was a sharp increase in the casualties incurred by the American sailors manning the boats. Thus the Army had no choice but to assist the Navy and deploy helicopters to protect the Navy boats from destruction. These operations required much night flying and coordination with the Navy’s riverine units, not an area of the Army’s expertise. At the same time, the Army’s expansion of ground operations increased its own requirements for the helicopters, resulting in a serious competition between the two services for them.

Early in 1966, the policy heads at CINCPACFLT (Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet), responsible for the administration of all forces in Vietnam, had become acutely aware of the requirement for armed helicopter support for riverine operations and had recommended to the Department of Defense the establishment of an armed Navy helicopter squadron in Vietnam. The planners specified the need for 44 Bell UH-1B Iroquois operational helicopters, 12 UH-1B pipeline helicopters, and 10 UH-1B training helicopters, for a total of 66. These single-engine helicopters had been used by the Army in Vietnam since 1962 and within four years had established a reputation for reliability and versatility. They were outfitted for close air support with the M-16 weapon system comprised of four external M-60 machine guns and two rocket pods, each housing seven 2.75-inch rockets.

In line with that request, several months later, in October 1966, CINCPACFLT also considered assigning the new AH-1G Cobra helicopters to the Navy but because they would not become operationally available until 1969, it was decided that “44 operational UH-1Bs would be acceptable to provide the earliest capability.” 2

But as sound as the request had seemed, “Those requirements were negated when the Secretary of Defense charged the Army with providing attrition aircraft and Navy aircrew training.” 3 A decision had thus been made that would have lasting impact on the establishment and early operations of the Navy’s critical air support program.

While awaiting the formal policy approval, the Navy was able to make a deal for some Army UH-1B model helicopters and form its own combat unit. Still, since the Army had priority for the UH-1Cs coming off the assembly line from Bell Helicopter, the Navy was assigned those UH-1Bs that had just been overhauled and were ready for redeployment to Southeast Asia. Those aircraft, inherently ideal for the mission of river patrol, nevertheless had serious shortcomings. The airframes had already been flown in combat and in many cases severely damaged and probably overstressed. In comparison to the newer “C” models being developed, they had less power, had older armament systems, and had a less maneuverable rotor system, the main element for controlling the aircraft. But because they were all the Navy could get, they were accepted.

The Navy Department had not initially planned for this mission and had no squadron designated for it, so aircrew personnel were requested from Helicopter Combat Support Squadron (HC-1), located at Ream Field in San Diego. In March 1966, Defense Secretary McNamara specifically approved the request from Paul Nitze, the Secretary of the Navy for the initial loan of eight UH-1Bs from the Army. It was to be followed by another 14 aircraft, as Navy aviation personnel became available to man them, raising the total to 22. McNamara, at CINCPAC’s request had, in fact, approved doubling the number of aircraft to 44. However, in December 1966, Nitze’s staff turned down the request for the second group of 22 aircraft, citing a shortage of second-tour helicopter pilots. 4 Surprisingly, only eight months later, in August 1967, there were 100 naval aviators assigned to the Navy’s newly formed squadron, Helicopter Attack (Light) Squadron Three (HA(L)3), nicknamed “The Seawolves.”

The arrangement for having Navy pilots fly Army helicopters was so accelerated that the Army became tasked with furnishing transition training to Navy pilots and their crews after they had arrived in Vietnam. In addition, all support functions were to be provided by the Army, including aircraft maintenance and provision of ammunition, fuel, spare parts, and support personnel. Barely a month later, the first six aircrews from HC-1 had been selected, had received their new assignments, and were on their way to the Republic of Vietnam. 5

For the most part, pilots volunteered to become part of this unique squadron unit heading to Vietnam for actual front-line combat duty. An Officer-in-Charge (OINC), Lieutenant Commander Joseph P. Howard was selected from HC-1 at San Diego, and off they went to the Mekong Delta, in support of inland riverine operations.

It was decided that the unit’s headquarters would be in Vung Tau, a former French beach resort east of the Delta. It was organized into four detachments (Numbers 29, 27, 25, and 21), each having two aircraft, eight pilots and eight gunners/crewmen. Detachment 29 was assigned to LST 786, Garrett County, a former World War II ship, designed to support two helicopters flying off her deck. She was located on the Bassac River, one of the critical tributaries of the Mekong. Detachment 27 was assigned to Nha Be, an important river town at the junction of the Long Tau and Soirap Rivers near Saigon. Detachment 25 would be at Vinh Long Airfield, an Army base adjacent to the Co Chien River. Lastly, Detachment 21 was assigned to LST 821, Harnett County, located upstream from Vinh Long and also anchored towards the center of the wide Co Chien.

During the winter of 1966, Commander Robert W. Spencer, a 37-year-old youthful and spirited officer who had begun his career as a naval aviation cadet, was serving on board the USS Valley Forge, LPH-8, as its Air Boss. After transporting the entire 326th Marine Amphibious Battalion, including equipment, to the port city of Danang, the ship returned to the Long Beach Naval Shipyard where Spencer took off for a family medical emergency.

Having performed in a commendable manner for two years, Spencer felt not only prepared, but primed for an assignment to command his own squadron. So one of the first phone calls he made upon his return was to his career detailer at the Bureau of Naval Personnel (BUPERS) asking for a squadron command assignment. The news was disappointing: “I wasn’t selected.”

Barely a week later, on February 14, while still ashore with his family, he was called by his commanding officer, Commander Charlie Carr, who told him, “You’ve been selected for squadron command. You’ve got a squadron.”

Spencer replied, “You’re pulling my leg. I just spoke to those folks and they said I wasn’t selected.”

Carr insisted, “You’ve got a command and I am making you available because I want you to have it.”

Spencer asked, “What is it?”

When Carr told Spencer that the squadron was called Helicopter Attack (Light) Squadron Three (HA(L)3), Spencer was flabbergasted. He was excited but also felt somewhat wary, since he hadn’t a clue as to the nature of this organization. “What was this helicopter squadron?” Spencer wondered. He had been named HA(L)3’s commanding officer before he knew anything about it.

Carr then told Spencer, “I want you to detach immediately, proceed to Fort Benning for six weeks, then from there to Camp Pendleton with the Marines for weapons training. When Spencer finally received his written orders, they already had him set to “report in-country by May 5th.”

For Bob Spencer, this would seem to have been an ideal opportunity, considering his qualifications and experience. First, he was interested in commanding a squadron, as it was for him a normal and necessary career sequence assignment. Second, he had combat experience and an excellent record flying attack and close-air support missions in the Navy’s formidable single engine AD Skyraiders over Korea in 1952. As a 22-year-old naval aviator just out of flight school, then Ensign Spencer was chosen by VA-65’s squadron flight leader to be his wingman as the second aircraft in a flight of 35 that successfully attacked the strategic and heavily defended Suiho hydroelectric plant in North Korea.

Spencer finished his Korean War tour aboard the USS Yorktown, flying a total of 42 combat missions alongside much more seasoned former World War II aviators. Of the many lessons learned in Korea, he could apply several to flying armed helicopters over the jungles, rice paddies, and rivers of Vietnam. They included ensuring that pilots remained conscious of but not fixated on their targets. He had learned that pilots should not fly directly over the enemy target and never fly parallel to terrain features so as to avoid being in the enemy’s line of fire and thus becoming an easy target. Adding to his credentials, Spencer had extensive experience as an instructor at the home of naval aviation at Pensacola, Florida both in SNJ and T-28 fixed-wing aircraft in 1954 and in HUP and H-13 helicopters from 1962 through 1964.

Prior to reporting to Fort Benning for training in the UH-1 helicopter, Spencer was tasked with putting together his team of officers, including the executive officer (XO) and the department heads. While he was in Long Beach, to his complete surprise, fellow Navy Commander Con Jaburg flew in from San Diego to meet with him and excitedly requested that he be his XO. Sensing that their “personalities just did not join,” Spencer was not entirely comfortable, but he nevertheless decided after speaking with BUPERS that he would not create a negative issue. Therefore, he gave his approval. Besides, since Jaburg was so passionate about wanting the position, it might just be a blessing.

In retrospect, under the circumstances, Spencer felt that he didn’t have the time to peruse “500 service records trying to determine or hand-choose these people.” Did Spencer feel rushed? “I detached in February, had six weeks TAD at Benning” (for UH-1 helicopter indoctrination and 20 hours of flight training). After Fort Benning, “I had to go to Camp Pendleton (for weapons familiarization) and to Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) school at Warner Springs, California, and then report to the senior naval officer present in Vung Tau, Republic of Vietnam no later than 5 May.” Since there were no other senior naval officers present in Vung Tau, CDR Spencer had essentially been instructed to report to himself.

After his arrival in Vietnam, things did not get any simpler for Spencer. After flying into Saigon and receiving the standard briefing at the Navy’s fenced-in and heavily sandbagged Annapolis Hotel, he flew with Jaburg and his “priceless and invaluable” Operations Officer Commander Ron Hipp to Vung Tau to get things going. Since no preparations had been made for their arrival, their first night was spent sleeping on cots in the hallway of an Army-run Vietnamese hotel. To find sleeping quarters, Spencer and his initial cadre of officers had to find berthing at the Cat Lo Coast Guard facility, a 15-mile ride from Vung Tau. Two weeks were spent there until permanent sleeping accommodations could be arranged at Vung Tau.

Spencer eagerly looked forward to at least one exciting event, the official commissioning of the squadron he had been designated by the Navy six weeks earlier to command. But even here, luck of the dice didn’t seem to roll for him as he discovered that the official commissioning ceremony of HA(L)3 had already been held in Vung Tau on April 1 by his HC-1 predecessor, LCDR Joe Howard. Undercutting Spencer by handing him the throne without the coronation would not bode well for the subsequent relationship between the Navy’s Vietnam command and the new helicopter squadron.

Spencer was utterly dumbfounded at the first briefing he received from the earlier assigned HC-1 personnel. In Howard’s absence, it was Lieutenant (junior grade) “Pistol” Boswell who imparted his wisdom to Spencer and his top officers. In a little area of the hotel serving hamburgers, “Pistol” started his briefing with, “Skipper, you’re going to love it here. All you have to do is fly and shoot.” Spencer recollects thinking hard, then getting up and walking to the men’s room, putting on his “sheriff’s badge” (commanding officer’s pin) and returning to ...