![]()

1

A short history of research

Robert Leighton

Antiquarians and first visitors

Before outlining the history of archaeological research at Pantalica, which essentially begins with the work of Paolo Orsi (1859-1935), this chapter reviews some of the ideas of earlier writers and visitors. The site aroused considerable interest amongst a wider public for several centuries prior to the establishment of archaeology as an academic discipline in the late 19th century. This was due partly to the location of its striking archaeological remains in a place of considerable natural beauty: an imposing promontory surrounded by a dramatic gorge, with innumerable rock-cut chamber tombs and shelters, and several caves, perforating the limestone slopes and cliffs (Pl. 1). Many more people would undoubtedly have visited the site prior to the easy availability of motorised transport had they not been deterred by the hilly terrain, the rough roads and hostelries away from the more familiar coastal itinerary, which was followed, in a somewhat prescriptive manner, by most foreign tourists to Sicily. While mainly intent on viewing the famous cities and monuments of classical antiquity, a trickle of curious and intrepid visitors is attested from the late 18th century, when Sicily was sometimes included in longer Italian or Mediterranean tours.

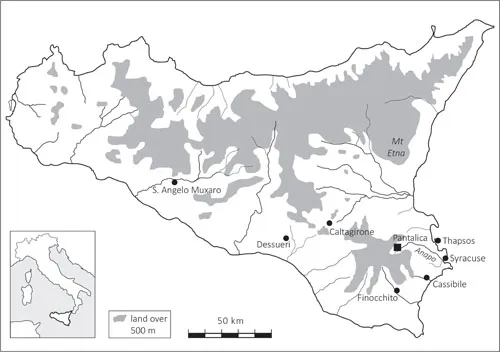

Reachable within a day from Syracuse, about 24 km away (Fig. 1.1), Pantalica was long known to scholars before Orsi’s time, even though it lacked any obvious historical or textual references antedating the Middle Ages. One of the earliest literary references to it appears in the Opus Geographicum (Kitab nuzhat al-mushtaq, or Book of Roger) by al-Idrisi, the 12th-century Arab geographer at the court of Roger II. He mentioned what seems to be the Anapo river, rising in the vicinity of Buscemi and meeting the sea near Syracuse, as the Nahr (river) Bentargha or Buntârigah (al-Idrisi 1840, 101-2; 1880, 104; 1999, 331). Since the Anapo skirts the southern flank of Pantalica a few miles downstream from Buscemi, it is generally thought that Bentargha refers to Pantalica.

It has sometimes been assumed that a place called Pentarga or Pentargo in historical documents of the 11th century is Pantalica (e.g. Fallico and Fallico 1978). Most notably, the chronicle of the 11th-century Benedictine, Gaufredo Malaterra, describes Pentarga as a place whose Arabic inhabitants or sympathisers were crushed politically and militarily in 1092 for rebelling against the Normans (Malaterra 1928, 98). In fact, a recent English translation of Malaterra (2005, 197) translates Pentarga as Pantalica. For this reason, Orsi (1910, 69) followed Amari (1868, 180-1) in maintaining that Pantalica was still inhabited at this date. If this is correct, one might surmise that the suppression of a revolt, which was reportedly followed by executions, lead to the abandonment of the place soon afterwards.

However, no other historical or archaeological sources provide clear evidence of any significant occupation at Pantalica in the 11th century. Moreover, alternative locations for Pentarga have also been proposed, notably Sortino, Palagonia and Scordia (Fallico and Fallico 1978; Arcifa, in press). The etymology of the name has also yet to be clarified (Caracausi 1993, 1160). That it derives from an Arabic reference to the prehistoric tombs or holes in the rock, as occasionally asserted on the internet or in tourist literature, is doubtful and probably the result of confusion with a comment by the Dominican friar, Tommaso Fazello, quoted below, who identified Pantalica with the ancient town of Herbessus, a toponym which he thought referred to rock-cuttings.

Fazello visited the site in 1555, when it was deserted, and described it at some length in his voluminous De Rebus Siculis. The main passage (lib. X, cap. 2) is here quoted from the Italian translated edition of 1830:

Fig. 1.1 Map of Sicily showing Pantalica and other Late Bronze Age and Iron Age sites.

Lontan da Ferula cinque miglia si trova Pantalica, città rovinata posta in una rupe, rotta intorno intorno, e tutta piena di caverne e spelonche, accerchiata di fiumi, e fortissima di sito naturale. Il significato e l’interpretazione del nome, e l’istesso luogo manifestano, che questa fusse la città d’Erbesso, la quale da Polibio e da Tito Livio è posta tra Siracusa e Leontini, e Tolomeo nelle sue tavole la mette tra Neeto e Leontino [sic], perchè questa voce Erbesso in greco latinamente vuol dire luogo pieno di spelonche. Questa città era grande e piena di caverne cavate artificiosamente, dove s’abitava, le quali ancor oggi sono maravigliose a vedere. Era disabitata anticamente questa città, siccome ella è ancor oggi, e con questo aveva anche perduto il nome per la mutazione del modo del chiamarla, e oggi essendo spento del tutto il nome antico, si chiama Pantalica, ed avea questo nome insin nel 203, come si legge nella vita di santa Sofia vergine e martire. Onde egli si desidera grandemente di sapere il suo nome antico, non ci essendo alcun vecchio scrittore che ne faccia menzione. Tutta volta io nel 1555 del mese d’agosto lo ritrovai, avendolo riconosciuto per la comparazion del sito e del luogo. Nel suo circuito non si vede altro, che una porta della città, ch’è volta verso Ferula, una fortezza rovinata e una chiesa, che si vede esser fabbricata alla moderna, la quale anch’essa è rovinata, e fuor di queste cose non si vede altro che oliveti, e una gran quantità di caverne cavate dentro a quelle rupi (Fazello 1830, 405-6).

It is surprising that Fazello makes no mention of tombs. Orsi (1899, 39) and Bernabò Brea (1994, 344) accuse him of having mistaken tombs for habitations, but this may be unfair since there are hundreds of rock-cut habitation chambers at Pantalica, many of which are cave-like. It is likely that Fazello was thinking mainly of these larger chambers, rather than tombs, when he wrote about manmade inhabited caverns. The “porta della città” on the Ferla side of the hill would correspond with a passage or point of access through the Filiporto ditch, also indicated in later sources (Gurciullo 1793, 48; Orsi 1899, 87; La Rosa 2004, 393), although nothing resembling a formal gateway survives today (chapter 2). The “fortezza rovinata” must be the “robusta torre” or “piccolo castello” noted by Gurciullo (1793, 49) and Orsi (1899, 68, 86) in the same area, which is still identifiable today, but heavily overgrown. It is curious, however, that Fazello, a man of the cloth, makes no mention of the rock-cut frescoed oratories of Pantalica (San Micidiario, San Nicolicchio and Grotta del Crocefisso), which might have been forgotten in his time, unless the “chiesa rovinata” refers to one of these; but his description (“Aede sacra recentis structurae prostratam”) suggests a different and collapsed, building, possibly the “anaktoron”. No other such structure is now known.

Apart from these direct observations, Fazello’s account is typical of the period for its concerns with toponymy and a semi-legendary saint, Sofia, supposedly martyred in the reign of Hadrian. She was also venerated as patron saint of nearby Sortino (Agnello 1963, 106-7). In a final passage (not quoted above) he speculates about the identity of the original inhabitants as Laestrygones or the Greeks of Iolaos. The attempt to identify Pantalica with the ancient town of Herbessus exemplifies a perennial interest in the location of ancient sites named in classical texts, several of which are unidentified to this day, including Herbessus (Orsi 1899, 88; Bejor 1989).

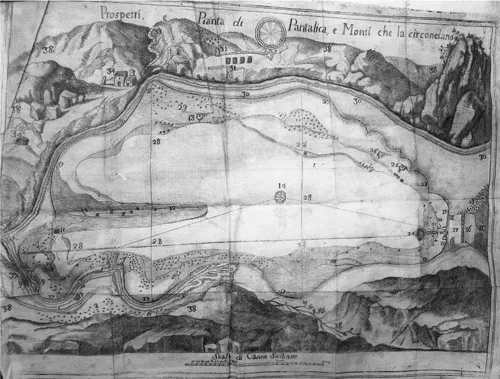

Fazello’s account was frequently cited over the next two centuries, more especially in connection with the whereabouts of Herbessus, which Cluverius (1619, 361) wrongly associated with modern Palazzolo Acreide (ancient Akrai). A more consistent interest in Pantalica, sometimes referred to as Pentarica, San Pantarica or Pentalica (Saint-Non 1786, 331; 1829, 462, 465) is more easily traceable from the late 18th century thanks to accounts by foreign visitors and some local scholars, most notably Andrea Gurciullo (1793), a priest of Sortino. Gurciullo’s booklet about Pantalica, few copies of which were printed, provides the most detailed account of the site before Orsi’s time and stands out for its description of monuments and for an admirable topographical plan, which includes numbered archaeological features, including the Filiporto (Fuor Porto) ditch and wall, various caves, the Christian oratories, and views of the surrounding hills (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2 Prospects and plan of Pantalica and surrounding hills (Gurciullo 1793).

Foreign visitors to Sicily in the 18th and 19th centuries, who were mainly French and British, were often interested in the landscape and natural history of the island, which raised questions about the identity of its original inhabitants (Tuzet 1955). A few with wider antiquarian interests, including Richard Colt Hoare (1817) in 1790, came to see not only Mount Etna but also the man-made curiosities of the Cava d’Ispica, a winding river valley whose steep sides are peppered with rock-cut monuments of different types and periods, from the Bronze Age onwards. It has more in common with Pantalica than with the classical ruins of Agrigento or Syracuse.

Another eminent visitor was the French geologist, Déodat de Dolomieu (1750-1801), whose account of Pantalica in 1781 was incorporated into the richly illustrated Voyage Pittoresque of Richard de Saint-Non (1829, 462-7; Lacroix 1918; Leighton 1989, 190), published in various editions from 1786, which also contains an engraving of the North necropolis (Fig. 1.3). Dolomieu was less interested in toponymic controversies than the visible remains and their physical context, especially the caves in the surrounding gorge, with their stalactites and bats, whose droppings provided material for saltpetre (Saint-Non 1829, 466). He recognised that the site was remarkable chiefly for its huge number of rock-cut tombs, perfectly explicable as burials for normal human beings rather than ancient giants (Laestrygones):

Plusieurs auteurs ont voulu que ces excavations servissent autrefois d’habitations aux Lestrigons, qu’on suppose avoir été les premiers habitants de cette partie de la Sicile; mais lorsqu’on les a examinées avec attention, on se persuade qu’elles ont été des tombeaux.... Ces grottes étaient fermées par une grosse pierre enchâssée dans le rocher; plusieurs le sont encore; les autres ont été ouvertes pas les paysans des environs, dans l’espérance d’y trouver de l’argent. Dans chaque chambre, il y a un petit gradin taillé dans la pierre, avec deux creux qui marquent la place de deux têtes. [Nb: these little steps are documented in some tombs (chapter 3), but not the hollows (creux) corresponding to the location of the skulls]. Quelques unes de ces chambres sont plus grandes que les autres, quelquefois du double; elles devaient renfermer alors quatre têtes ou plus. Le nombre de ces tombeaux, qui garnissent tous les rochers des environs, doit faire supposer une immense population…. Je visitai plusieurs de ces excavations et j’y trouvai encore des ossemens et des têtes; on m’avait assuré qu’elles était d’une dimension gigantesque, mais elles ne me parurent pas au-dessus des proportions ordinaires; d’ailleurs la longueur des chambres dans lesquelles les corps étaient étendus, indique que ces anciens Lestrigons n’étaient pas au-dessus de la taille actuelle des Siciliens (Saint-Non 1829, 463-5).

Fig. 1.3 “Vue des Grottes de San Pantarica dans le Val de Noto près du Lieu où étoit autrefois l’antique ville d’Erbessus” (Saint-Non 1786, pl. 129).

Visitors in the early 19th century include a landscape painter, Carl Gotthard Grass, who described Pantalica in his Sizilienische Reise (Grass 1815, 340-5). The famous geologist, Charles Lyell, came to Pantalica in 1828, as recorded in one of his letters. His Sicilian tour was primarily concerned with dating volcanic eruptions from stratigraphic observations as part of his wider research on the age of the earth according to geological observations (Rudwick 1969), although he was also curious about a site “where a vast population once lived underground” (Lyell 1881, 222). It would appear that the geologist and palaeontologist William Buckland (1784-1856) had asked him to look for fossil bones, presumably in support of his theories, expounded in Reliquiae Deluvianae, about the universal flood (Buckland 1823): “Made a man dig, by Buckland’s direction, into stalactite, but the instrument was so bad, I was obliged to go away after four feet were dug into, and no signs of a bottom, or bones” (Lyell 1881, 222). He comments on little else regarding the Pantalica trip, except the shabbiness of local accommodation, the terrible state of the roads and the snail’s pace of his journey from Syracuse to Pantalica, which took two days.

The British artist and writer, Edward Lear (1812-88) visited Pantalica in the spring of 1842, where he recorded his impressions in sketches (Fig. 1.4) and a letter of 5 June.

All this rock – for the space of 2 or 3 miles is perforated with artificial caves – each large enough to contain 2 or 3 persons – & cut with a raised bed or seat at one side…. There are about 3 or 4 thousand of these caves in the most inaccessible crags – & tradition calls them the houses of Troglodytes: – other antiquarians say they are tombs – & to this opinion I incline – though why they should have buried their dead in such places passes all belief.... during the persecutions of the 3rd and 4th. centuries by the Roman Emperors, – these caves were used as refuges by the early Christians – for many remains of crosses & other representations of that time character are traceable on the walls of some of these strange places (Noakes 1998, 57-8).

Fig. 1.4 EdwardLear (1812-1888). “Pantalica”. Yale Collection for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, Record 3750124.

He was also amused by the idea of troglodytes, who appear in later sketches (1847) of the Cava d’Ispica, also noted for its large rock-cut chambers (Proby 1938).

Félix Bourquelot (1815-68) visited Pantalica from Sortino in September 1843. He had already seen “grottes sépulcrales”, a type of monument that was widespread in southeast Sicily but which “…a été peu étudiée, malgré l’intérêt réel qu’elle présente” (Bourquelot 1848, 191). Pantalica’s tombs reminded him of a giant honeycomb. Like Dolomieu, he noted the production of saltpetre in the Grotta della Bottiglieria ou de la Merveille, the stalactites of another cave, the Grotte Neuve (probably another name for the Grotta Trovata) and the inaccessibility of most tombs (Bourquelot 1848, 194). He also observed the painted frescoes of the rock-cut oratories (Grotta del Crocifisso, San Micidiario), and discussed the use of some Sicilian caves, such as those of the Cava d’Ispica. as habitations, and others as tombs.

George Dennis (“Dennis of Etruria”, 1814-98) made four trips to Sicily between 1847 and 1863, and produced the guide to the island for John Murray, in which Pantalica has a full entry (Dennis 1864). Recognising the primarily funerary nature of the remains, he proposed that the residential quarter was “on the height at the junction of two deep and converging ravines”, but he was wrong to regard all the rock-cut chambers as tombs and discount the idea of habitation chambers (Dennis 1864, 366). His account also contains some puzzling unconfirmed claims: that certain tombs contained arched niches for cinerary urns and that the Grotta della Meraviglia was also used for burial.

The Murray guide served a growing number of visitors in the later 19th century and anticipates the early 20th-century guidebooks or books about Sicily, in which the unspoilt beauty of Pantalica, “picturesque in the extreme” (Dennis 1864, 366), as well as its archaeological remains were deemed worth a visit despite difficulties of access. By this time, published descriptions and accounts often show a good knowledge of Orsi’s work. Between 1923 and 1956 it was also possible to make use of the local Syracuse-Vizzini railway, subsequently dismantled, in order to reach the site. This was the means of transport adopted by King Vittorio Emanuele III when he visited Pantalica in 1933, before continuing his tour on the back of a mule.

The campaigns of Paolo Orsi (1895-1910)

With the exception of padre Gurciullo, the descriptions of visitors to Pantalica were often effusive but lacking in scientific value and, inevitably, based on very superficial knowledge. The first official excavation of a tomb evidently occurred under the supervision of the honorary inspector of Antiquities at Syracuse, one E. Lo Curzio, but is poorly recorded (Fiorelli 1879). Orsi’s predecessor at the Syracuse Museum, Francesco Cavallari (1876, 283-4), had also been to Pantalica, while Orsi’s first impressions are recorded in a letter of 1889 (La Rosa 2004, 390). At the time of his first campaign in 1895, therefore, Pantalica was a known site with a certain mystique, but had never been the subject of serious or systematic study. ...