1

Producing the Frontier

Suddenly, as if a whirlwind had set down roots in the center of town, the banana company arrived, pursued by the leaf storm. A whirling leaf storm had been stirred up, formed out of the human and material dregs of other towns, the chaff of a civil war that seemed ever more remote and unlikely. The whirlwind was implacable… . In less than a year it sowed over the town the rubble of many catastrophes that had come before it, scattering its mixed cargo of rubbish in the streets.

—Gabriel García Márquez, Leaf Storm (1955)

In preparation for his trial El Alemán wrote a book-length manuscript on the history of Urabá. One of the first sections of the text bears the title “Urabá: A Land without a State.”1 It begins with a story about an engineering mission that set out for Urabá from Medellín in 1927. It took the group five weeks of travel by car, foot, horseback, and boat to reach the waters of the Gulf of Urabá. According to El Alemán, the mission had to bushwhack much of the way, so the “only guide for navigating through the treacherous jungles” was a lone telegraph line.

The leader of the mission was Gonzalo Mejía, a famous businessman from Medellín and a “visionary antioqueño,” according to the jailed paramilitary chief (antioqueño is someone from the department of Antioquia). Mejía helped pioneer so many modern industries in Colombia, including automotive, aviation, and cinema ventures that the press had dubbed him “the dream maker.”2 But his most ambitious plan of all was the one that had led him to trudge through the swamps of Urabá: the construction of a road connecting Antioquia’s capital of Medellín to the department’s only outlet to the sea, the Gulf of Urabá.

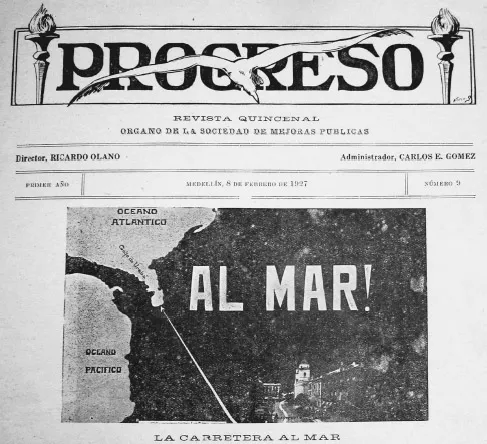

Through an elaborate marketing and public relations campaign, Mejía had whipped up a frenzy of support for the project among his fellow antioqueños. Medellín’s newspapers fanned the excitement, predicting the road would be Antioquia’s “magnum opus.” Mejía and his allies claimed the “Highway to the Sea,” as they branded it, would be “una obra redentora” (a redemptive public work).3 The Highway to the Sea inspired nothing less than a creole version of Manifest Destiny, but rather than Horace Greeley’s “Go West, young man,” the call was “¡Hacia Urabá! ¡Al Mar!” (To Urabá! To the Sea!)4

Antioquia’s version of Manifest Destiny had just as racialized an underpinning as its U.S. counterpart and was based on the same master narrative of all frontiers: the duel between civilization and barbarism. “Yes, we’re heading west to both civilize and civilize ourselves,” wrote one newspaper columnist, “to repel barbarism and attract healthier elements of morality and work.” He described Urabá as the unconcluded business of colonial conquest: “Let’s finish what those audacious Spanish conquistadors were unable to do: subjugate and exploit that promised land.”5

Despite the feverish enthusiasm behind it, the construction of the two-lane road, spanning a mere two hundred miles, dragged on for three decades. The Highway to the Sea opened in 1954, two years before Mejía’s death. The project stalled repeatedly due to administrative disarray, the financial strains of the Great Depression, and the ruggedness of the terrain. In his manuscript El Alemán points out that the rainy season still occasionally renders the highway impassable, a fact he laments as proof that “even today, the road is holding back Urabá’s genuine progress.” In his eyes the civilizing mission begun by Mejía remains, “even today,” a work in progress.

The torturous construction of the Highway to the Sea exemplifies the paradoxical quality of frontiers as spaces produced by both the power and the limits of reigning regimes of accumulation and rule. On one hand, frontiers are spaces undergoing profound material transformation, epitomes of the “wreckage upon wreckage” witnessed by Walter Benjamin’s angel of history, its face turned toward the past and a violent storm caught in its wings. “This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned,” wrote Benjamin, “while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”6 And yet frontiers are also spaces in which these storms of “progress” have supposedly not yet run their course. Frontiers, then, are made by forces that somehow manage to be both brutal and brittle.

They achieve this contradictory feat because frontiers are consummate examples of what Lefebvre meant by the social production of space: frontiers are ideological and discursive formations as much as material ones; they are, in every sense, both real and imagined.7 The symbolic realm of, say, myths and maps are just as integral to their production as the physical materiality of, say, railroads and landscape transformations. Frontiers are also inherently relational spaces: every frontier is the frontier of somewhere for someone. In the case of Urabá, the somewhere was Medellín and the someone was the city’s light-skinned, ultraconservative elites.

The historical–geographical contours of Urabá’s production as a frontier zone was driven by a profoundly racist set of cultural politics emanating from the city. Following a classic metropole–satellite relation, the frontier emerged via Medellín’s attempt to bring the gulf region into the city’s cultural, political, and economic orbit, and the construction of the Highway to the Sea was a central part of this process.8 The relationship turned into a form of uneven development: the accumulation of wealth by a small elite in Medellín was systematically linked to the accumulation of exploitation and poverty in Urabá.9

In the language of Latin American dependency theory, Medellín’s relationship with Urabá was a form of internal colonialism, a term with intentionally racialized overtones.10 As a concept, internal colonialism highlights the way in which the uneven development of Urabá as a frontier zone was as much a racial and cultural process as a structural effect of the geographies of capitalism. However, the fact that this form of colonialism is primarily internal or subnational does not mean it happens in a vacuum; internal colonialism is not divorced from forces operating at other scales. Indeed, as I show, the making of Urabá into a frontier was the product of global interconnections: from the tentacles of the United Fruit Company to the wide-ranging geopolitics of the Cold War.

Urabá’s statelessness in these years was problematized and expressed from the point of view of Medellín through racialized idioms of civilization and barbarism and claims about the region’s lack of progress and abandonment. As late as 1950 an army fact-finding mission reported, “The place is dreadfully abandoned; there’s no Inspector, no Police, no official form of authority of any kind.”11 Driven by the imperative to resolve these problems, the frontier effect unleashed a succession of state projects in Urabá led by urban elites based in Medellín.

Frontiers as Racialized Spaces of Uneven Development

Frontiers have a long and infamous history in Latin America.12 As the product of colonial discourses, frontiers in the region are as old as Christopher Columbus’s first letters from the Caribbean and the early myths of El Dorado. Once Latin America gained independence from Spain, frontiers became an integral part of the ways in which early nation builders shored up fledgling forms of national identity. Perpetuated by everything from the geographical expeditions of Alexander von Humboldt and his successors to Domingo Sarmiento’s influential classic Civilization and Barbarism, frontiers were what the new “imagined communities” of Latin America were to be formed against.13 They became, in the words of the anthropologist Margarita Serje, “the opposite of the nation.”14

Race and identity were central to why these spaces were cast out as areas beyond the pale of the nation. In post-Independence Colombia, as elsewhere in Latin America, the idea of mestizaje (racial mixture) came to define national identity in ways that encompassed the multiracial makeup of the country without undermining the core ideology of white supremacy. Mestizaje allowed elites, alongside their darker-skinned compatriots, to rally around the imagined community of Colombia as a mestizo nation while still emphasizing their own whiteness and superiority. By disparaging Afro-descendent and indigenous identities, mestizo nationalism further marginalized spaces, such as Urabá, where these racialized groups formed a majority of the population.15

Informed by ideologies of scientific racism from abroad, nationalist discourses turned race and nature into conjoined essentialisms that further exoticized, racialized, and thus produced entire swaths of national territory as unincorporated “savage lands.” In Colombia the racialized projection of frontiers as spatial Others was part and parcel of extremely violent forms of resource extraction and the hyperexploitation of their populations—from the genocidal rubber booms of the Amazon to the cattle enclosures of the country’s eastern flatlands.16 In a vicious feedback loop, the racialized poverty and exclusion resulting from these neocolonial projects reinforced the frontier imaginary that helped cause these problems in the first place.

The long history of Urabá’s experience with racialized colonial violence could be said to begin with the fact that it was the site of Spain’s first colonial settlement on the mainland of the Americas. The indigenous Urabaes put up fierce resistance to the Spaniards.17 Urabá was also where the Crown sent enslaved Africans to mine for gold along the banks of the Atrato River, giving the region a solid place within the geographies of the Black Atlantic. Many of those who escaped slavery formed autonomous maroon communities in the jungle, setting an early precedent for the region’s enduring reputation as a fugitive space. In short, Urabá was an early crucible of colonial violence.

For centuries, however, it remained a sparsely populated region of scattered fishing villages, tiny family farms, and trading posts. It was much more connected to the maritime networks of the Caribbean than to the major cities in the interior of the country. But all this started to change when a confluence of events pushed Medellín to take a greater interest in the region. The city’s elites increasingly saw the need for a road or railroad to the coast as a cultural, economic, and geopolitical imperative. One event in particular set things in motion.

Major national attention only turned toward Urabá after the United States engineered the 1903 secession of neighboring Panama, which had until then been a department of Colombia. The Panama debacle was the culmination of a multidimensional crisis. A severe economic depression had deepened age-old political schisms between the Liberal and Conservative parties, plunging Colombia into a bloodletting known as the War of a Thousand Days (1899–1902).18 The political and economic turmoil had the added misfortune of coinciding with one of the most aggressive periods of U.S. imperialism toward Latin America.

With an eye on U.S. ambitions in the region, a Colombian diplomat passing through the department of Panama in 1902 predicted that its loss was simply a matter of time: “The Isthmus is lost for Colombia; it is painful to say it, but it is true. Here Yankee influence predominates, and all Panamanians, with few exceptions, are capable of selling the Canal, the Isthmus, and even their own mother.”19 With the canal’s construction stalled and with the War of a Thousand Days having further stoked preexisting separatist sentiments, Washington seized the opportunity to nudge, bless, and militarily defend Panama’s declaration of independence on November 3, 1903.

The loss of Panama left a deeply wounded sense of nationhood along with a serious case of geopolitical paranoia. Rafael Reyes, Colombia’s new president, immediately moved to forestall any further dismemberment of the nation. He called for an administrative–territorial reorganization of the country that would centralize power in Bogotá and partition the country’s departments into smaller, more manageable units. President Reyes’s plans turned into a chance for Antioquia to reclaim its territorial jurisdiction over Urabá, which it had lost to the department of Cauca during a previous national shakeup. As Reyes pushed his reforms through Congress, land-locked Antioquia, led by its capital, Medellín, tapped into the country’s lingering geopolitical anxieties to lobby for its repossession of Urabá.

With Panama as the subtext, Medellín’s city council implored Congress “to return territory that has always properly belonged to Antioquia, thus placing the area on the road to progress and helping defend our national integrity.”20 After all, went the argument, it was hardy antioqueños who just decades earlier had settled the lands to the south of Medellín, turning them into Colombia’s “eje cafetero” (coffee axis). As the creators of the country’s mighty coffee boom, antioqueños—or paisas, as they call themselves—claimed they had a proven track record of spearheading a successful mission of civilizing untamed lands and turning a profit in the process.

The colonization of Colombia’s coffee heartland is one of the founding myths of paisa (pronounced pie·sa) exceptionalism. A play on the word “paisano” (countryman), paisa is, in its ugliest incarnation, a chauvinistic regional–cultural identity assumed by people from the highlands of Antioquia and a few neighbor...