eBook - ePub

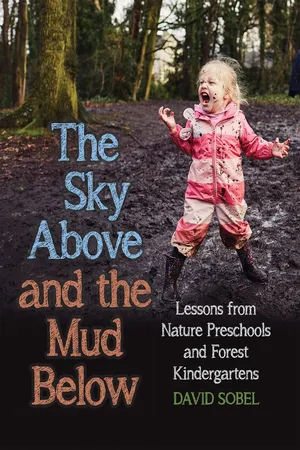

The Sky Above and the Mud Below

Lessons from Nature Preschools and Forest Kindergartens

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

David Sobel's follow-up to Nature Preschools and Forest Kindergartens walks readers through the nitty-gritty facts of running a nature-based program. Organized around nine themes, each chapter begins with an overview from the author, followed by case studies from diverse early childhood programs, ranging from those that serve at-risk children to public preschools to university farm programs to Waldorf schools.

Sample newsletters in each chapter show how real programs have tackled tough questions and sticky situations. The programs featured in these newsletters are from across the United States: Maryland, New York, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Alabama, Connecticut, Illinois, Vermont, California, Michigan, Rhode Island, Louisiana, and Indiana.

Sample newsletters in each chapter show how real programs have tackled tough questions and sticky situations. The programs featured in these newsletters are from across the United States: Maryland, New York, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Alabama, Connecticut, Illinois, Vermont, California, Michigan, Rhode Island, Louisiana, and Indiana.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sky Above and the Mud Below by David Sobel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Early Childhood Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Getting Organized

CHAPTER 1

Before Taking Children Outside

Taking children outdoors is full of promise and laden with challenges, especially if they’re used to school being indoors most of the time. Going outdoors means recess, and recess means outdoor voices, climbing on the monkey bars, and getting as far away from the teacher as possible. Going outside also potentially means the neighborhood dog will trundle in to nuzzle the children and disrupt your activity, the grounds crew will start mowing the grass right next to your outdoor classroom, the wind will blow the children’s worksheets off the table into the poison ivy, and someone will have to pee as soon as you settle in under the big white pine. So much for just smelling the roses.

Whether you’re starting a nature preschool from scratch or you’re a kindergarten teacher who wants to get the children outside more, you’d be wise to focus on that old scouting mantra: be prepared. And being prepared means more than tucking your pant legs into your socks and bringing a first aid kit along. Here are the top ten things (roughly in order) you need to accomplish before you start to take children outdoors:

TEN THINGS TO DO BEFORE HEADING OUTSIDE

1. Assess potential hazards in the environment. Conduct a risk assessment of the outdoor spaces you’ll be visiting. Are there yellow jacket nests, poison ivy, potential encounters with dangerous animals? (Later on, you’ll learn about the big-animal drill they do in Victor, Idaho, where it’s possible to encounter bears or moose!) You’ll also want to look for broken limbs still hanging in trees, old barbed wire, and other potential hazards that children might not notice. Modest risks are good—they provide appropriate challenges that encourage learning for your children. It’s your responsibility to allow for acceptable and appropriate risk (slippery, not-too-steep slopes). Hazards are things your children can’t assess or manage on their own, and it’s your responsibility to eliminate them or avoid them. Therefore, you have to spray the yellow jacket nest or not go in that section of the forest. Or, you can ask the maintenance staff to cut down the broken limb over your outdoor classroom meeting area. Use modest risks to your advantage; eliminate or avoid hazards.

2. Differentiate between recess and outdoor learning. Figure out how you will make it clear that outdoor time is different from recess. Yes, the children will have some free nature playtime, but there will also be circle time, story time, sit spots, and outdoor lessons. Outdoor learning time has the same kinds of expectations as indoor learning.

3. Develop techniques for outdoor group management. Developing a set of management techniques that will keep children both safe and engaged outside is important. Hannah Lindner-Finlay’s guidelines in this chapter have got you covered here. Let me suggest an additional modestly stern but effective technique: The first time you take children outside, make it clear that you will walk in the front of the line, and no one will go ahead of you. Otherwise, everyone must come back inside. As soon as you pass through the door to the school yard, walk slowly and allow an energetic child or two to bolt past you into the inviting sunshine. Immediately use your whistle or teacher voice to call everyone back, and walk them back inside. Then sit them in a circle and remind them about the rule that the teacher walks in front of the line. Tell them if they can’t follow this one rule, then you won’t be able to do outdoor learning. Ask them if they can follow this one rule. If they agree, try going outside again. If the children are successful, praise them and then engage them in an activity. If some children rush ahead, take them back inside again and say you’ll try again tomorrow. Mean what you say—it works like a charm!

4. Create risk-management plans for potential risky behaviors. In addition to removing hazards, decide ahead of time what kinds of risky behavior should be encouraged or avoided. If there are small climbable trees, what will you do when children want to climb them? Do you allow the children to hop across the little stream? How will you visually create boundaries in the woods so children know where they’re not allowed to go? Maryfaith Decker’s protocols in chapter 3 on tree climbing, playing near water, and cold- and hot-weather guidelines are components of a risk-management plan.

5. Identify the affordances of the environment that support play and learning. Affordances are opportunities for engagement. Look for them while conducting your risk assessment of the landscape. A tree trunk on the ground, at just the right height, affords comfortable sitting. A pine-needled forest floor with no vegetation under a grandmother white pine affords a perfect circle gathering spot. Lots of dead branches on the ground afford fort building. The slippery slope affords problem solving: “How can we be sure that everyone can get up this slope safely? Can you help your friend?”

6. Align outdoor activities with your curriculum standards. Teachers at a public school nature kindergarten program in the Sooke, British Columbia School District were initially concerned about whether the children’s academic progress would be compromised. The plan was to have the children outside in the morning and inside in the afternoon—inside in the afternoon so they could make sure they had enough time to address the academic aspects of the curriculum. But after the first three months, the teachers found that academic skills were just as easily developed outside as inside.

When I visited one of these classrooms, teachers introduced the letter S inside, and then everyone went outside. The children walked S’s in the dewy grass in the field. Once in the woods, they made S’s on the ground with sticks and pinecones. During circle time, they named things they’d seen that morning that started with S—sunshine, spruce, salmonberry, sand. Later chapters articulate clearly how such outdoor play activities—both teacher-led and children-initiated—meet the local early childhood curriculum standards.

7. Learn phenology—the science of what’s happening now in the woods and fields around you. Nature-based early childhood teachers need to be knowledgeable about both child development and natural history. One without the other is not sufficient. It’s why we have a Natural History for Early Childhood course in our program at Antioch New England. You should know some of the mushrooms that emerge in the fall and where you’re likely to find them. You should know the difference between goldenrod and aster, and which berries are edible and which are toxic. Pokeberries (toxic) look a whole lot like blueberries (edible) to children. Can you tell the difference?

In the winter, learn how to tell whether a raccoon or skunk has been visiting the compost pile. Which birds overwinter in your area and are likely to come to your feeders? When do snow fleas start to appear, and how can you find them? When and where will the first wildflowers emerge in spring? What are vernal pools, what will we find there, and why are they important? And which birches are best for bending? (Don’t know about this lost New England pastime? Read Robert Frost’s “Birches.”) Have a collection of natural history guides for your area in your indoor space so both you and the children can browse them.

8. Know the personalities and dispositions of the children in your group. Are any of the children in your care “runners” (children who are prone to taking off and not stopping)? You’ll want to know the answer to this question before you head out into the field with no clear boundaries. Familiarize yourself with the children’s fears and dispositions in more bounded settings before moving into more unbounded settings. Again, Hannah’s guidelines later in this chapter nicely articulate moving children from indoors to a nearby outdoor space on the play yard and practicing rule behavior before moving farther afield. This will allow you to understand which children are afraid of worms, which children need to be close to an adult, which children might have trouble keeping their hands to themselves, and so on.

9. Know the previous outdoor learning experiences of the group. This is a corollary to the previous guideline. It’s important to know if the children have prior experience learning outdoors. Did last year’s teacher conduct a day in the woods? Do children already know about appropriate clothing? Acclimated children need very different treatment than a group that is not outdoors savvy.

10. Dress for success. That means both you and the children. Being outside for hours in the winter in northern climates requires lots of preparation. Everyone is going to need really warm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: Why The Sky Above and the Mud Below?

- Part I: Getting Organized

- Part II: Curriculum

- Afterword: The Path Forward

- Appendix: What Do We Mean by “Ready”? A Review of Research Behind Nature-Based Early Childhood Education Programs

- References

- Index