CHAPTER 1

Seeking “Old Opportunity”

Ted Wharton knew that show business would be a tough profession to crack. The early years that he spent on and behind the stage, though, gave him an invaluable introduction to virtually all aspects of the entertainment industry, especially to the performance and production of melodrama (the predominant form of theater in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century). They also taught him the technical and improvisational skills that would serve him well as he graduated from vaudeville performance and legitimate stage acting to direction of film shorts and production of serials, particularly since he—like his brother Leo and other pioneering filmmakers in those transitional years of the early 1910s—was often experimenting as he developed the conventions and devices that would become staples of later cinema and television.

Getting into the Business

Theodore (“Ted”) William Rubenstein (later changed to Wharton, his mother’s maiden name) was born on April 12, 1875, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.1 His parents William and Frances (“Fanny”) Rubenstein, sister Eugenia Alice (“Genie,” born 1864), and brother Leopold Diogenes (“Leo,” born 1870) had emigrated from England in 1873.2 William, who was originally from Bohemia, worked as a merchant in Milwaukee; Fanny kept the house. By 1880, the Rubensteins had relocated to Hempstead, Texas, where Ted was raised. (He later joked in a newspaper interview, “When I was four years of age, my parents moved to Texas, and, feeling duty-bound, I went with them.”)3

After William’s death in 1882, the family moved to Dallas, where young Ted held short-term jobs as a messenger for Bankers and Merchants National Bank and as a clerk in the auditor’s office of the Texas and Pacific Railway.4 But even at an early age, he felt the draw of the theater and determined to make his career in the entertainment industry. Over the next decades, he sought out various positions both in the business end of the profession and on the stage as an actor,5 gaining the confidence and the expertise needed to break into the burgeoning film business.

While still in his teens, Ted secured a job as assistant treasurer and then treasurer of the Dallas Opera House. Although that experience deepened his passion for the performing arts, he realized that “life would be more interesting on the stage than ‘counting the house.’” So, in 1895, he moved to Saint Louis, where he spent two seasons acting with the Hopkins Grand Opera Stock Company.6 The company, which advertised itself as being “composed of popular favorites who [had] won their way to public recognition through artistic and meritorious effort,”7 was organized and operated by the honorifically titled “Colonel” John D. Hopkins, a former associate of P. T. Barnum and a prominent and colorful figure in vaudeville management in the Mississippi Valley for over three decades. A small-time actor turned big-time impresario, Hopkins introduced the popular daylong “10–20–30,” a low-admission continuous show that comprised drama and between-the-acts vaudeville and drew large and enthusiastic audiences into his circuit of theaters.

The Grand Opera House building that Colonel Hopkins took over in the mid-1890s was a familiar and cherished local landmark. And while the programs he offered there varied, one thing about them remained constant: they were always sensational. One week’s bill, for example, included the nineteenth-century melodrama The Two Orphans starring the popular Kate Claxton, who had created the lead role, along with European acrobats and hand balancers, singers, comedians, dancers, a hanging wire performer, and a hat manipulator. In fact, it was not unusual on any given day for acts as disparate as Fulgora, an impersonator of world famous generals, and Professor de Berssell, a “funny French modeler in clay,” to appear on stage beside bamboo bell ringers and thoroughbred racehorses.8

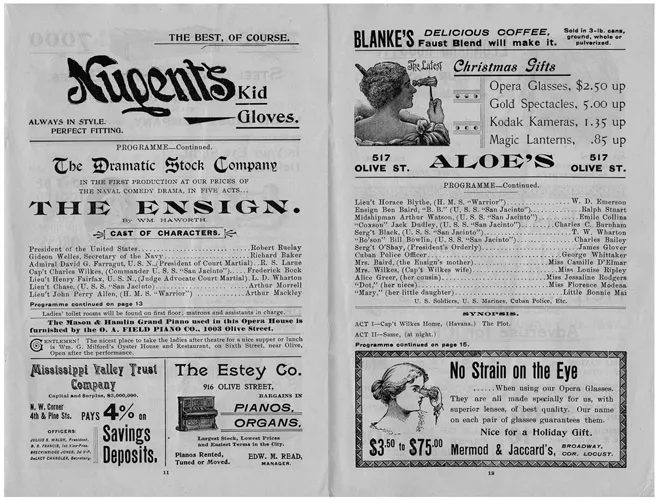

Surviving programs confirm that Ted appeared in numerous “continuous performance” productions at the Hopkins Grand Opera, where he occasionally worked with his brother Leo, who was also a member of the company. In January 1896, for example, the brothers had small roles in William Haworth’s The Ensign. Originally performed in Washington, DC, in early 1892, the five-act naval war drama was based on the Trent Affair of 1861, an international diplomatic incident that occurred during the Civil War and threatened war between the United States and Great Britain. An American warship, the USS San Jacinto, had intercepted the British mail packet RMS Trent and removed two Confederate diplomats who were bound for Britain to enlist military and financial support for the South. Unwilling to risk war, President Lincoln resolved the crisis by disavowing, but not apologizing for, the actions of the San Jacinto’s captain and releasing the envoys.9

FIGURE 1.1 Both Ted and Leo Wharton performed at the Hopkins Grand Opera in Saint Louis. Occasionally, as in The Ensign (January 1896), they appeared together.

Widely performed, The Ensign was a hit with both theatergoers and actors. (Film pioneer D. W. Griffith, who played the role of Lincoln in a production at the Alhambra Theatre in Chicago in the early 1900s, would later lift some of the Lincoln scenes for his film The Birth of a Nation.)10 It was likely quite familiar as well to the audiences who viewed the Hopkins staging in Saint Louis, in which Ted, billed as “T. W. Wharton,” appeared as Sergeant Black, an officer from the San Jacinto, while Leo, billed as “L. D. Wharton,” was cast as Lieutenant Henry Fairfax, the judge advocate. Featured on the same bill with The Ensign that week were several vaudevillians, comedians, musicians, and another “specialty of merit”: a demonstration of the “American Biograph,” leased from the American Mutoscope Company at the outrageous cost of $500 a week. Said to be “the most marvelous invention of the age,11 that early motion picture device may have whetted Ted’s curiosity and possibly given him his introduction to the emerging cinema industry.

Colonel Hopkins’s influence in the entertainment industry was broad and far-reaching,12 and his Saint Louis company provided an excellent training ground. Yet even in the waning years of the nineteenth century, New York was the place where most American actors aspired to be, and Ted was no exception. So when the opportunity arose to join the company of the Lyceum Theatre to act in conventionally staged dramas that carried more cultural prestige and legitimacy than the vaudeville in which he had gotten his start, he happily relocated to New York.13

Considered to be quite modern at the time of its construction on Fourth Avenue in 1885, the Lyceum—with an interior designed in part by Louis Comfort Tiffany, an electrical installation said to have been supervised by Thomas Edison himself, and amenities such as an elevator car—was home to a stock company that included many of the most talented actors of the day, some of whom went on to find success on the silent screen. Established by playwright Steele MacKaye and producer Gustave Frohman (one of three Frohman brothers who were active in show business), the company evolved from the original Lyceum School of Acting to the New York School of Acting and finally to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. After debt forced MacKaye and Frohman to sell their interests, Gustave’s older brother Daniel became manager and producer, a position that he held for more than two decades, even after the old Lyceum Theatre was razed in 1902 and the new Lyceum opened on Forty-Fifth Street in the heart of the Broadway Theater District.

The company performed numerous plays each year—more than eighty during Daniel Frohman’s tenure—and also employed troupes of actors and musicians who toured the plays, most of which were sensational melodramas or historical dramas. During his time at the Lyceum, Ted worked with highly regarded actor (and later silent screen star) E. H. Sothern; and he acted alongside other members of the company in productions such as The Sporting Life (1898), a popular four-act, sixteen-tableaux melodrama written by Cecil Raleigh and Seymour Hicks about a young British lord who incurs heavy debts and must decide whether to allow his horse to throw a race in order to redeem his losses.14

After his appearance in The Sporting Life, Ted transferred to Charles Frohman’s Empire Theatre Company, which, like the Lyceum, was famous for the stars that it developed—among them William Gillette, John Drew Jr., and Ethel Barrymore (whose brother Lionel would later be cast in the Whartons’ The Romance of Elaine serial). Brother to Gustave and Daniel, Charles was a noted theatrical personality who is credited with creating the star system on Broadway. A great promoter of playwrights, he was the force behind multiple hits before his untimely death in May 1915 during the torpedoing of the Lusitania,15 a tragic event that would prove central to several of the Whartons’ later serials.

As part of Empire’s stock company, Ted appeared in The White Heather, a successful British melodrama written by Henry Hamilton and Cecil Raleigh, in which a scheming nobleman is willing to go to any extreme to maintain his position of privilege.16 The play—which ended with a spectacular underwater diving operation to recover a lost ship’s log that confirmed the legitimacy of the marriage of the nobleman to the woman he “ruined” and the paternity of their child—was scenically outstanding, full of the plot and character exaggerations that defined the genre. An unqualified hit, it premiered on November 22, 1897, and played for 184 performances, during which time “the Academy of Music, large as it is, hardly suffice[d] to accommodate the audiences the play attracts to its doors.”17 Ted also appeared in a supporting role in another Frohman production, A Marriage of Convenience, a four-act comedy of manners that opened on November 8, 1897, at the Empire Theatre and starred prominent actor John Drew.18 A period piece set in the time of Louis XV and based on Un mariage sous Louis XV by Alexandre Dumas, the play, originally adapted for the British stage by Sydney Grundy, was an excellent study of a newlywed husband, the Comte de Candale, who is “all worldliness and ease,” and his charming “girl-bride,” who is “all innocence, truth and timidity.” According to the Tammany Times, it “pack[ed] them in like sardines.”19

Since aspiring actors often moved between theaters and up to better companies, it was hardly surprising that, at the urging of his cousin Lena Ruben-stein, Ted soon left the Empire Theatre to join the New York company of Augustin Daly, another influential theater manager, critic, and playwright. Lena, the wife of actor Creston Clarke (nephew of Edwin and John Wilkes Booth and son of Junius Brutus Booth, all of them distinguished stage actors) and herself a frequent performer on the New York and London stages under the name Adelaide Prince, had earlier spent almost five years with Daly, whom she introduced to Ted.20

Widely considered “the autocrat of the stage,” Daly exercised tight, almost tyrannical control over all his productions. At the same time, he advanced the careers of the actors in his company—Ada Rehan, Maurice Barrymore, Maud Jeffries, Tyrone Power Sr., and Isadora Duncan, among them. Ted became part of the stock company, and upon Daly’s death in 1899 he assumed the position of stage manager for the road tour of The Great Ruby, a “perennially interesting pageant melodrama” that appealed to young and old alike and that would be revived several times over the next decade (with Leo Wharton appearing in one of those later productions).21 The play was the kind of big, splashy, turn-of-the-century production that audiences had come to enjoy. Revolving around the theft of a large ruby from a Bond Street jeweler’s wife by a gang of thieves, it offered numerous excitements and plot contrivances typical of the melodrama of the period, including frequent changes of scene that ran the gamut of fashionable English life. In the exciting climax, the jewel thief tries, unsuccessfully, to effect his escape by jumping into a balloon, a scene that, the Argonaut reviewer observed, “in theatrical parlance, [was] ‘simply great’” and eclipsed anything seen in other productions.22

The staging of such a fast-paced melodrama was certainly a challenge, but evidently one that Ted welcomed, since he subsequently assumed similarly demanding positions with other New York production companies. His last two seasons of theatrical life were spent as manager of the famous Hanlon Brothers’ Superba company and as acting treasurer of Hammerstein’s Victoria Theatre in New York.

Superba, as its name suggests, was nothing short of superb. A “unique mechanical and pantomime spectacle” that drew heavily on the popular traveling circus tradition long linked to theater,23 it was created, arranged, and performed by the Hanlons, whose vaudeville act originally consisted of six British-born brothers.24 All were talented gymnasts and acrobats who eventually became successful theatrical producers and are now considered by some to be the fathers of musical comedy.25 In 1890, the three surviving brothers created their final production, Superba, a pantomime that grafted their signature acrobatic slapstick onto fairy-tale plots with remarkable tricks and transformations, and each year for the next two decades they reworked it to fe...